BROKEN FRONTIER AWARDS – BEST COLLECTION OF CLASSIC MATERIAL NOMINEE!

Misunderstood in his short lifetime, mangaka Takashi Fukutani strove to give voice to the downtrodden through his art, drawing candid depictions of Tokyo’s working class youth in the 1970s and ’80s. Now, six years in the making, a new aizoban edition of Dokudami Tenement from Black Hook Press sees Fukutani’s cult gekiga manga translated into English for the first time, bringing his ever vital work to a wider Western audience, and offering an overdue celebration of an under-appreciated artist.

Depending on which direction you choose to read it – I started with the supporting materials at the back of the book – the collection is prefaced by perhaps the most detailed biography of Fukutani to exist. Pieced together by editor Mitsuhiro Asakawa from documents and meetings with the artist’s friends and relatives, we learn that Fukutani lived an itinerant, hand to mouth existence, struggling to find permanent employment or to keep down personal relationships. Money tight, he turned to selling his clothes to buy alcohol, meaning he would often show up to job interviews drunk, and in his pyjamas.

Unwilling to conform at the price of his integrity by drawing action or genre comics that might earn him a regular wage, Fukutani persisted with his decidedly less commercial brand of absurd fetishes and seedy anecdotes in Dokudami Tenement; a series published weekly which would garner a loyal following, and continue for almost twenty years. Yet as alcoholism took greater hold, inspiration and enthusiasm waned, and deadlines were consistently missed, Fukutani resorted to plagiarising ideas from other mangaka, attracting criticism from the industry. By the age of 48, Fukutani had drunk himself to death, disgraced and penniless.

Unwilling to conform at the price of his integrity by drawing action or genre comics that might earn him a regular wage, Fukutani persisted with his decidedly less commercial brand of absurd fetishes and seedy anecdotes in Dokudami Tenement; a series published weekly which would garner a loyal following, and continue for almost twenty years. Yet as alcoholism took greater hold, inspiration and enthusiasm waned, and deadlines were consistently missed, Fukutani resorted to plagiarising ideas from other mangaka, attracting criticism from the industry. By the age of 48, Fukutani had drunk himself to death, disgraced and penniless.

The story of the artist draws instant comparison to that of his shiftless protagonist, 26-year-old Yoshio. “No job, no money, no woman. A left-behind man, late off the starting line of life”, narration describes. We meet Yoshio in his filthy 2 x 3m tatami room; his greasy hair hanging around his shoulders, his last remaining possession to not yet have been pawned off is the futon he sleeps on, the floor so littered with garbage and roaches that one might easily mistake the building as long ago condemned. Yet Yoshio somehow goes on living, “like a stubborn weed”, with a perpetually goofy countenance and a freewheeling attitude to each new day. The reader is promised “a shocking and scandalous tale of exhilaration and despair” in the stories to follow, divided into ‘Sun is Shining’ parts 1, 2 and 3, ‘The Fetishist’s Lament’, and ‘Midnight Mover’ – each of which is wildly hilarious and grotesquely exaggerated.

‘The Fetishist’s Lament’ is the most perverse episode, as Yoshio meets and learns the ways of a social outcast with a most bizarre sexual predilection that will have readers wincing in horror, screaming with laughter, or a combination of the two. Eyes bulge, brows sweat, noses drip and flies swarm around faces that explode into larger than life expressions. Yet, as one might expect from Fukutani’s life story, the visceral comedy of Dokudami Tenement is tinged with an underlying discomfort. Beneath his bravado, Yoshio is the kind of desperate character one might recognise and be best to avoid in real life. He’s the guy who ingratiates himself to the role of harmless friend, only to later peep through the keyhole to spy on you sleeping; the guy who says he’s buying at the bar but leaves you to pick up the tab at the end of the night.

Yet at the same time he attracts a genuine sympathy from the reader. When pretty Miko moves into the room next door in ‘Sun is Shining’, Yoshio is motivated for the first time in his life to find work and make money, and takes a back-breaking job in construction to afford a gift for her; a necklace which ultimately finds itself in the trash when he fails to win her heart. The only salve for Yoshio’s loneliness is whisky, and we soon find him face-down in a gutter. “I was gone so far that the warmth of my own puke reminded me of the warmth of a woman’s body”, reads the thought bubble above his head.

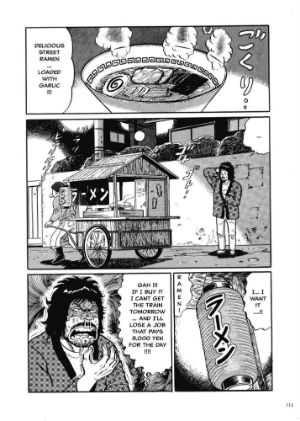

By the book’s final instalment, ‘Midnight Mover’, we recognise that in spite of all the jokes, Yoshio is living in actual poverty. He’s so hungry he can’t sleep, yet buying food will cost him the train fare to make a job the next day. With the gas and water cut off at his home, he can’t even prepare a meal of instant noodles, and ends up being conned by an exorbitant street vendor. By the story’s conclusion we see him squatting in an alleyway, defeated and with his pants around his ankles; “I’ll never forget the feeling of eating ramen with my hands while shitting in the pouring rain”, reads the final, full splash page.

Another casualty of capitalism’s cruelty, Yoshio barely scrapes through each day, without having any real chance in life. What’s initially presented as youthful freedom soon becomes frustration and humiliation as Fukutani highlights the inhumanity of the Japanese social system, which we’ve seen before in such slice of life manga as Takashi Murakami’s Stargazing Dog. Yet where that Eisner-nominated story and others convey their message through tearful sentimentality, Fukutani chooses outrageous comedy as his weapon of choice; the ludicrous exploits of his problematic anti-hero providing just as effective a social comment as sugary stories that make us cry.

An unapologetically truthful artist who lived life on his own terms, Takashi Fukutani used Dokudami Tenement to speak not only for himself, but for the disenfranchised, working class youth of Japan in the 1970s and ’80s. Pushing the boundaries of good taste, his work was largely misconstrued by readers in his time; a fact that broke his heart and, editor Asakawa argues, influenced his untimely death. Yet, some four decades on, Dokudami Tenement is still wickedly funny, and still strikes a meaningful chord. With a further two volumes now available to preorder, the Dokudami Tenement collection from Black Hook Press finally gives Takashi Fukutani the recognition that might have saved him in his lifetime.

Takashi Fukutani (W/A) • Black Hook Press

Review by Ally Russell