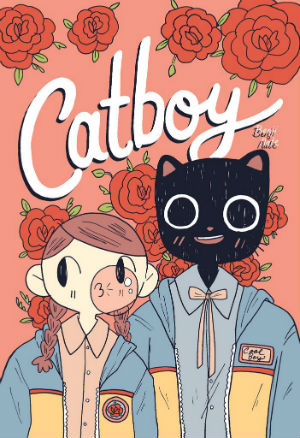

Catboy by Benji Nate is a collection of twenty-two short comedic vignettes following the life of hapless young artist Olive and her equally bumbling cohort Henry, the titular human/cat hybrid. While there is no central narrative arc, Catboy perfectly captures much of the fumbling through life in your mid-20s experience that artists go often through. What makes this collection special is the inherent sweetness and charm that Nate approaches the subject matter with makes the reader come to love both Olive and Henry. In a world that is unkind to our protagonists we feel reassured in the knowledge that their friendship will pull them through.

Much of the comedy in Catboy comes from the inability of both our protagonists to fully function in the world. On a surface level the feline Henry’s magical transformation into a human-sized fully verbal friend for Olive (after she wishes on a shooting star) brings on all sorts of complications. He is not interested in the breakfast burrito she tries to serve him, nor is she interested in the various dead birds and rodents he brings to her.

Much of the comedy in Catboy comes from the inability of both our protagonists to fully function in the world. On a surface level the feline Henry’s magical transformation into a human-sized fully verbal friend for Olive (after she wishes on a shooting star) brings on all sorts of complications. He is not interested in the breakfast burrito she tries to serve him, nor is she interested in the various dead birds and rodents he brings to her.

All of Henry’s ridiculous problems stem from his impossible hybrid existence. In still going to the bathroom like a cat Henry pees all over his feet, despite his massively increased size he still tries to sleep at the top of the bed, he can’t get a job at the café Olive works at because he would get fur in everybody’s coffee. Yet as he sees these problems with a cat’s mentality, he is only bothered by them when they are an obstacle to him getting more pizza.

While we laugh at Henry because he is a clown, the ludicrousness of his problems allows Nate to slide Olive’s much more universal problems subtly past our defenses. Working a crummy café job and unsuccessful in her art career, Olive’s wish to morph Henry into his present form feels inspired by her lack of friends as an adult. Though never explicitly stated, across the vignettes we can see the quarter-life crisis Olive is going through. It’s one that is highlighted by the contrast of her life to that of rich cool girl Dixie who takes a shine to the gregarious Henry, much to Olive’s dismay.

Henry for all his buffoonery also serves as a contrast to Olive. His job pet-sitting unruly dogs nets the pair enough to finally furnish their living room with something other than blankets on the floor. He outpaces her at figure drawing class, and gets along better with her parents at dinner. Olive’s father pestering her about not being a successful artist while praising Henry as a “self-made man” is just part and parcel of the many small but constant defeats she has to go through.

No matter how much of a pain Henry can be though, Olive is lucky to have him as her friend. He is the one who is there to console her when an anticipated lunch date turns out to be just an offer to teach an art workshop for kids. He is the one who give the middle finger to the manager at a graphic design firm who won’t hire Olive due to her lack of experience. When she is sick he tries his best to make her well, even if he bungles it by putting a slice of pizza in hot water and calling it soup. He is there again when Olive can’t break through the force field of chatter of the fancy successful people at Dixie’s party. So that when she finds herself selling her paintings on the street intoxicated on wine Henry stole from a gallery opening, the light in this sad, drunk, and hungry moment is Henry’s simple desire for pizza and, of course, a last minute sale to local charming twee boy Jean.

For all Olive’s tribulations, Nate takes special care to let the reader know that there is a joy to her life. Each vignette begins with a full-page illustration of the duo in their outfits for the coming scene. They are always smiling and radiant in these transitions, so that no matter how the previous vignette has ended, we begin the next with an image of our unflappable protagonists showcasing their best looks. The two function almost as children’s dress-up dolls with their constantly changing outfits and giant-eyed cartoon faces. This playfulness extends into the fact that Henry always wears an outfit made of Olive’s wardrobe. That no comedy or drama is ever created from a boy wearing female-coded clothes nor that a human-sized cat is walking around on two legs suggests a more utopian world where no one is judged for their appearance.

There is another interesting choice being made by Nate in that Henry’s child-like nature is mirrored in not only Olive, but in the overall aesthetics of the comic. Many of her panels are held together by the use of inviting soft pastels – yellows, blues, and pinks that give the work the appearance of a children’s comic. This discordance between the storybook visual and the more adult worries is what captures the particular feelings that Olive is going through so well. She is at a time in her life when she is still partially a child but also has to pay rent. Yet she is constantly unable to clear the hurdles that would land her in full adulthood leaving her stuck in forever in the middle.

Olive is not the only one, as a telling scene in which she and Henry have a slumber party features a round of talking about boys they like. Going against stereotype for a scene like this her friend Fran talks about her dog Quark, while Henry’s favorite boy is the old man who feeds the birds in the park. That there is barely any discussion of romance and none of sexuality lends a whimsical innocence to the stories told in Catboy.

It also reinforces the work’s main theme that the platonic friendship between Henry and Olive is the most important and special relationship in their lives. While the transition from childhood to adulthood is more traditionally marked by the prioritization of courtship over friendship, Nate directly taps into a more modern outlook on adult friendships.

The amount of work Nate has produced this early on in her career as a cartoonist is often staggering and much of it is worthy of further examination. Still, Catboy serves as both a highpoint and a strong introduction to her talents as a cartoonist. She is able to craft cartoonish characters that feel both deeply real and highly animated. Her ability to render emotion even on the face of an angry pug is superb.

While the stories in this collection are short and simple they are constantly funny and frequently resonant. It will be interesting to see how she pushes her craft forward from this point, be it longer and more nuanced storylines, greater visual complexity, or continued refinement and perfection of the techniques she is working with here. Whichever direction she pursues the sky is the limit for Nate.

Benji Nate (W/A) • Silver Sprocket, $20.00

Review by Robin Enrico