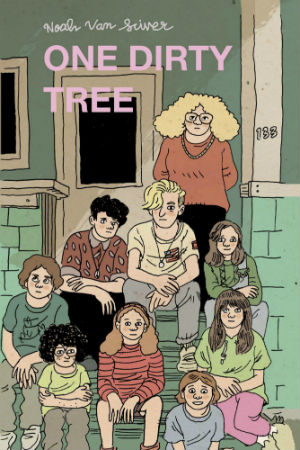

The nature of autobiographical comics forces the cartoonist to examine their past and try to assemble meaning from it. Noah Van Sciver in his book One Dirty Tree from Uncivilized Books seeks to draw the line between his experiences growing up in an impoverished house full of children to the fissure developing between himself and his current girlfriend. In a confident decision, he leaves much of the work of making that connection up to the reader, resulting in a work that trusts the audience to stitch together the thematic threads of a loose narrative and draw their own conclusions.

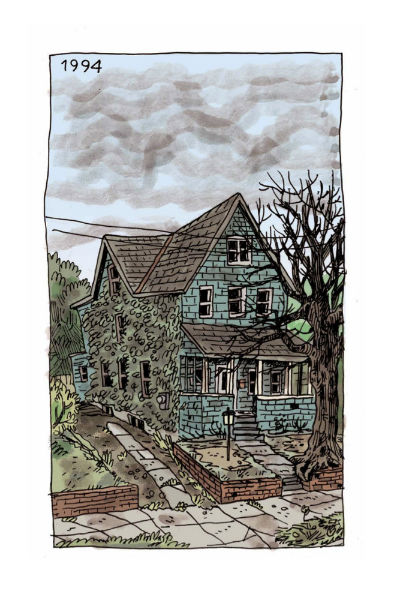

The first time period that Van Sciver focuses on is his childhood growing up in New Jersey in the early ’90s. From the beginning there are multiple unspoken indications that his family is not well off. The splash page introducing his family’s home at the time prominently features the titular dirty tree’s roots spilling over onto the sidewalk. The ivy climbing up the outside of the house is a slimy shade of green and even the sky is streaked with brown clouds. On the inside we see chipped paint and splintering floorboards. An early panel of the nine children gathered around the bed to pray recalls imagery of pioneer families doing the same, linking the hardship faced by both groups. Further hints of the family’s poverty seep through as we see Noah complain to his mother about being hungry, which will become a reoccurring theme throughout young Noah’s life. Even more telling of the family’s dysfunction is an incident in which Noah is forced to take a bath in a tub previously filled with dirty dishes and, failing to wash his hair, is then once again forced into the tub as a bucket of water is poured over him by his father.

The first time period that Van Sciver focuses on is his childhood growing up in New Jersey in the early ’90s. From the beginning there are multiple unspoken indications that his family is not well off. The splash page introducing his family’s home at the time prominently features the titular dirty tree’s roots spilling over onto the sidewalk. The ivy climbing up the outside of the house is a slimy shade of green and even the sky is streaked with brown clouds. On the inside we see chipped paint and splintering floorboards. An early panel of the nine children gathered around the bed to pray recalls imagery of pioneer families doing the same, linking the hardship faced by both groups. Further hints of the family’s poverty seep through as we see Noah complain to his mother about being hungry, which will become a reoccurring theme throughout young Noah’s life. Even more telling of the family’s dysfunction is an incident in which Noah is forced to take a bath in a tub previously filled with dirty dishes and, failing to wash his hair, is then once again forced into the tub as a bucket of water is poured over him by his father.

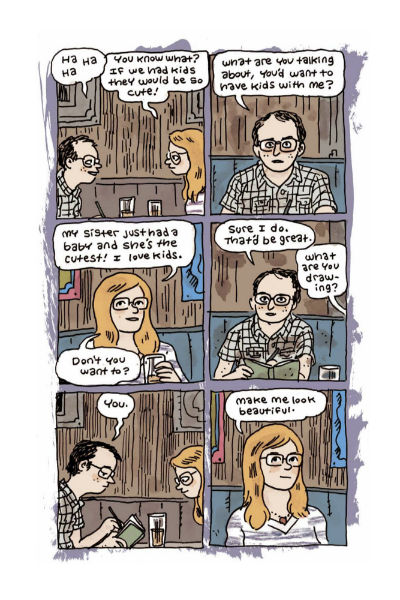

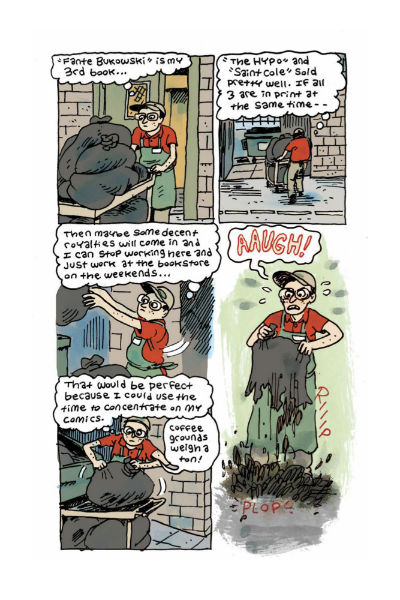

These scenes are presented with only the barest commentary from Van Sciver and, while he gives some exposition at the book’s front, he cuts direct from the scene in the bath to himself in 2014 contemplating how to celebrate the completion of his first Fante Bukowski book. Even in this triumphant moment, he is worried about money. His girlfriend Gwen asking him to meet her at an expensive bar only compounds his apprehension. Through their dialogue it becomes apparent that she is worldlier and comes from a higher income class bracket than he does. Noah is embarrassed at his inability to cook or drive, but the shame he feels at not having graduated college is telling. Gwen’s performance tells us all we need to know about how much she takes these things for granted. Even understanding that his family might not have the money to send him to college, she assumes that his father would have encouraged him in finding a career. While Van Sciver saves the full reveal of his father’s dereliction of duty for the end of the story, already the reader can start to put together the reasons that Noah is so unprepared for adult life.

The book continues this pattern of intercutting between incidents in Noah’s childhood and the slow dissolution of his relationship with Gwen without much commentary as to overall message. The powerful thing about that choice is that it speaks to the way in which our lives don’t follow a simple metanarrative where one thing is the direct cause of another. An idea that is also reflected in one of the childhood sections the juxtaposes young Noah playing out Jurassic Park with other kids in the neighborhood, being admonished by a neighbor’s mother for kissing her daughter and then high-fived by his own mother, and lastly being beaten with a belt by his father for making too much noise at night. These instances all exist in the same continuum. The happy childhood memory is as present as the violent one. And in keeping with many instances of child abuse, the violence appears without warning, its threat looming over the reader ever after.

Things grow ever more complex when Van Sciver discusses his family’s history in tandem with his parents’ Mormonism. In the most direct section of the book, Van Sciver shows his father’s slow decline and ties it to the Mormon belief in growing a large family. The stress of supporting nine children while not allowing his wife to work, per the traditions of the religion, becomes a crushing weight on Noah’s father. Van Sciver devotes an entire page to illustrating this very metaphor. Again eschewing a simple narrative, the reader now has less ability to cast Noah as the victim and his father the villain. This doesn’t assuage his father’s wrongs, but it (along with the revelation that he was diagnosed with bi-polar disorder) adds context to them. In a visual touch that seems metaphorical rather that verisimilitude, Noah’s father in the height of his dysfunction with his long hair, stubble, and bandana has the appearance of every burned-out hippie used to symbolize the crushed optimism of the middle of the 20th century. Noah’s father has failed him, but so to has the father been failed by his ideology.

This failure then suggests the question of whether Noah’s religion has failed him as well? Confronted by one of Gwen’s friend’s questions regarding how much money he makes as a cartoonist, Van Sciver depicts himself turning into a pathetic sniveling monster. He grapples with that fact his craft has consigned him to a life of poverty but as he cannot deviate from this course he only hopes for understanding. It soon becomes clear from his conversations with other cartoonists as well as his interactions with Gwen that this understanding is unlikely. The real once again feels metaphorical when we see Noah contemplating a conversation between himself and Gwen where her focus is on having children while his is on drawing. Here in tandem with Noah it starts to dawn on the reader that both he and Gwen have very different goals for their lives.

To be so revealing about one’s personal life is always a bold choice for an artist, but Van Sciver’s bravest choice here is how straight he plays everything in comparison to his earlier work. Scenes from his youth such as fossil hunting or attending church don’t dabble in the self-aware awkward comedy seen in My Hot Date. A scene in which Noah is deflated by his boss and then has a garbage bag rip open on his feet is paced and rendered like a comedic scene out of Fante Bukowski or Blammo, but within the surrounding context of One Dirty Tree it reads as yet another indignity. Van Sciver needs to maintain this more painful tone for Noah’s later explosions at Gwen for mocking his Mormon upbringing to feel earned. It equally earns the reader’s shared relief and subsequent unease at that relief when Noah’s father disappears. Most of all it earns the downbeat ending where Noah having broken up with Gwen sits in the apartment he will soon vacate and realizes, “these are the cleanest walls I’ve ever lived inside.” The stability and he never had as a child existed within those walls, but he was never fully at home there, so he must leave.

Van Sciver’s art is as always excellent. In a story so focused on characters emotions it is the performances that will make or break the audience’s engagement. In this regard One Dirty Tree is a masterclass in rendering emotional performance. The more overly cartoony reactions are well within his wheelhouse, but it is performance like the small pitiable young Noah playing with his Mellow Mutt Triceratops toy that show cases his ability to capture all the subtly of a character’s performance. We see it again in the way he depicts the cruelty in his father’s grin during the forced bath. Or in Gwen’s inability to understand the way Noah’s upbringing has permanently hobbled him in trying to be a “normal” adult. His coloring is equally strong giving the settings a strong sense of lighting and texture. Smudges of off-model color do much to make both the world and the characters feel lived in and organic.

On a formalist level his pages here are variations on a six-panel grid structure that frequently tightly frame only the character that is speaking. The largest mechanical storytelling flourish used is the occasional splash pages which bookend and serve to transition between many sequences. Save for the details indicating the squalor in his childhood home, Van Sciver employs little environmental storytelling. None of this is a major issue as there is little reason for a more personal domestic story of this type to delve to deeply into more cinematic storytelling. Knowing his ability to beautifully render an expansive landscape it does feel odd that he takes few opportunities to fully set his characters within the setting other than in splash page drawings.

However, every time he draws the front of the titular house the choices he makes particularly in color brilliantly evoke the frustrated destitute tone he seems to be going for. So that in the final shots when we see him and his brother starring at the house as adulst with a blue sky and white vinyl siding on the outside, the contrast between this image and the way the house has been presented up until this point lets the reader know how much time has moved on from that difficult past.

One Dirty Tree is a work that speaks to complex ideas in a subtle voice. It is a brave approach to take in a genre that is frequently didactic. Yet Van Sciver’s gamble completely pays off here. He masterfully evokes frustration and joy in a way that respects how inseparable the two are from the human experience. Leaving room for the reader to connect to his experience through the parts of it that remind them of their own struggle to create a future for themselves in the face of an ever-present past. In stepping out into difficult territory and handling it with grace he further cements his status as one of the foremost cartoonists working today.

Noah Van Sciver (W/A) • Uncivilized Books $19.95

Review by Robin Enrico

[…] Robin Enrico takes a deep dive into ONE DIRTY TREE by Noah Van Sciver, “a work that speaks to complex ideas in a subtle voice. It is a brave […]