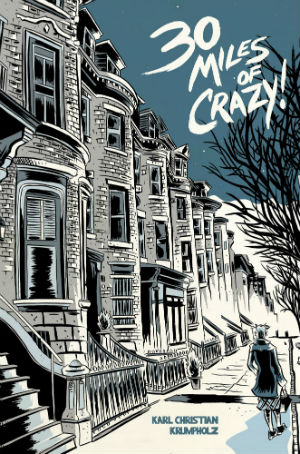

In the realm of small press comics we often get to see an artist advance, but we rarely see them age. In issues #5 and 6 of his long running 30 Miles of Crazy! series Karl Christian Krumpholz provides an interesting look into the type of work a indie cartoonist might do in their middle age. Collecting several recent strips from the webcomic, these issues show Krumpholz taking a more focused approach to the ethnographic work he has been doing throughout the series. Turning his eye outward from the bar culture of earlier issues to capture a larger sense of the titular 30-mile Colfax Ave in Denver Colorado by interviewing the people who inhabit it. Krumpholz cedes a lot of the camera in these recent issues but in becoming more of a documentarian he demonstrates not only a keen ear but also a clear eye for how to use his cartooning to capture a certain ecstatic truth about his world.

In the realm of small press comics we often get to see an artist advance, but we rarely see them age. In issues #5 and 6 of his long running 30 Miles of Crazy! series Karl Christian Krumpholz provides an interesting look into the type of work a indie cartoonist might do in their middle age. Collecting several recent strips from the webcomic, these issues show Krumpholz taking a more focused approach to the ethnographic work he has been doing throughout the series. Turning his eye outward from the bar culture of earlier issues to capture a larger sense of the titular 30-mile Colfax Ave in Denver Colorado by interviewing the people who inhabit it. Krumpholz cedes a lot of the camera in these recent issues but in becoming more of a documentarian he demonstrates not only a keen ear but also a clear eye for how to use his cartooning to capture a certain ecstatic truth about his world.

In 30 Miles of Crazy! Krumpholz gathers his content from a combination of his own stories and his interviews. Previously Krumpholz curated his stories to revel in the more chaotic and the ridiculous side of being a bar-goer, leading to short punchline driven strips. In issues #5 and 6 the strips are both longer and denser than in previous issues, and in letting things breathe it allows for his subjects to have a far more fleshed-out existence. So, while many of his interviews happen within the confines of a bar, Krumpholz is using this communal meeting place to allow his subjects to drop their defenses and talk about their lives outside of it.

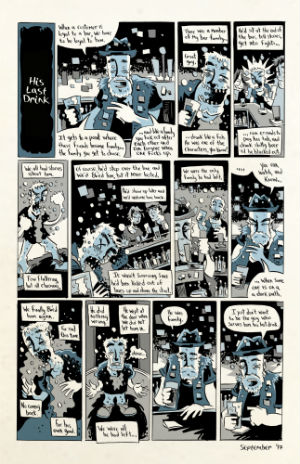

This broadening of focus then serves as a simulacra of the conversations a bar-goer might have with assorted strangers; be it the woman who licks fine art, the failed optimist who only finds company in the books she reads at the bar, or the homeowner who recounts how the neighborhood has changed in the last fifty years. We also hear a few reflective stories from bartenders such as the bar owner who frets over selling the bar that has been passed down through his family for generations due to gentrification, or how a troubled patron was banned from another bar due to the bartender’s fear of being the one to serve him his last drink.

One interview subject discusses how the gay scene has changed since he moved to Denver, while in another interview a group of middle-aged women discuss their deep frustration at having lived so long in a patriarchal culture. The sixth issue’s closing image of Krumpholz frantically scribbling down notes about the women’s conversations reminds us of the deeply unguarded yet ephemeral nature of these conversations for everyone but the participants.

Just as being in a bar drops our guard enough to allow us to tell personal emotional stories, so too does it give us space to discuss the darker sides of life. Krumpholz’s interviews equally capture this undercurrent of danger and seediness surrounding the bars on Colfax Ave. In one, the proprietor of a local tattoo parlor discusses an incident in which a man who had been shot in his abdomen came into his shop asking for someone to call an ambulance, only for his assailant to come into the same shop an hour or so later trying to hide from the police.

Picking up a running thread from previous issues, Krumpholz himself narrates the hard luck story of local sex worker Sweet Caroline. It’s a difficult territory he’s navigating here, as the late Caroline cannot tell her own story and Krumpholz is only an observer relaying the story she told him about herself, yet his retelling feels almost wistful rather than exploitative. Sex work is very much a part of the world he is trying to chronicle, but it is a mature choice to make the emotional core of Caroline’s story more about a losing a fellow patron than her profession. That is how he knew her, so that is how he will mourn her.

In a similar evolution of another reoccurring theme in the series, the sixth issue opens up with an interview with a homeless man who resides on Colfax Ave. It seems the longer Krumpholz documents the local population, the more sensitive he become to their plight. In doing so he gives them more and more room to tell their story with him as a conduit. The same editorial control is there but, as with all the best documentary work, editing it works best when that craft becomes invisible to the audience. That he closely follows this interview with another in which a bar patron’s generosity towards another homeless person is paid back in violent threats skillfully lets the reader draw their own conclusions about the morally complex world he is observing.

This window into the world of Colfax Ave is perhaps the thing that most recommends Krumpholz’s work on 30 Miles of Crazy!. This world of older drinkers is one that is rarely touched on in the youth-oriented world of indie comics. As a middle-aged man Krumpholz is certainly not outside the archetype of the cartoonist, yet he fits into neither the family man nor the misanthrope categories associated with that age of artist. He and his wife live among the people for whom the local bar is a large part of their social sphere. For some it is a vital center, for others the last refuge. It is Krumpholz’s age and maturity that allows him the distance to appreciate and document the spectrum of lives that intersect at this common ground. For as under-represented as voices of individuals like Krumpholz are in our comics, far more so are the voices those he interviews represented in culture. Like all great ethnographers, his true work is in earning his subjects’ trust and creating a platform for them to tell their stories.

This window into the world of Colfax Ave is perhaps the thing that most recommends Krumpholz’s work on 30 Miles of Crazy!. This world of older drinkers is one that is rarely touched on in the youth-oriented world of indie comics. As a middle-aged man Krumpholz is certainly not outside the archetype of the cartoonist, yet he fits into neither the family man nor the misanthrope categories associated with that age of artist. He and his wife live among the people for whom the local bar is a large part of their social sphere. For some it is a vital center, for others the last refuge. It is Krumpholz’s age and maturity that allows him the distance to appreciate and document the spectrum of lives that intersect at this common ground. For as under-represented as voices of individuals like Krumpholz are in our comics, far more so are the voices those he interviews represented in culture. Like all great ethnographers, his true work is in earning his subjects’ trust and creating a platform for them to tell their stories.

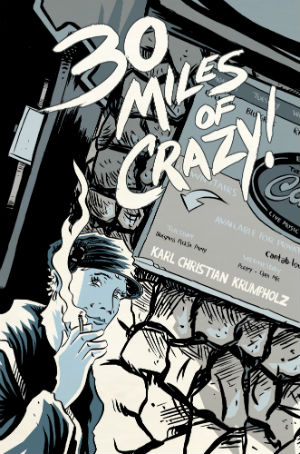

Attention should also be paid to Krumpholz’s artistic craft in presenting his subjects. His decades of working in the medium affords him the distinctly Slave Labor Graphic style of his cartooning. That they even published his earlier fictional work in the mid 2000s should come as no surprise. So far removed from the heyday of these stylistic touchstones though, Krumpholz ends up having a unique style for the modern era. The way in which his monster movie square-jawed faces with angular bodies and checkerboard teeth pairs with his far more grounded subject matter creates a work that feels historically unique. In many ways a more traditional realistic style would rob the visuals of the appropriately rough atmosphere he is trying to convey.

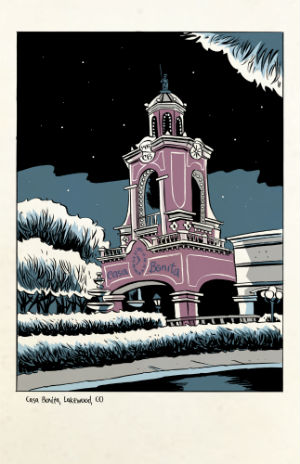

Krumpholz has reached a solid point with his cartooning in his 30 Miles of Crazy! strips. He mixes crisp black and white line work with blue and grey highlights, and his brushy thick black shadows give his panels a real energy and movement that nicely counterbalances the more staid digital coloring. Though his subject matter frequently confines him to indoor settings he will break up interviews with painstakingly rendered exterior shots to help better set both the scene and the mood in their composed silence.

The most advanced of his compositional decisions is the way he positions his camera for the interviews that function primarily as monologue. While Krumpholz will occasionally cut away to the subject in another location for emphasis, the height of his craft is in the way he will subtly pan the camera within the medium shot of the speaker and deftly shift the physical performance of his subjects. This added motion is not only needed to successfully translate this documentary standard into the comics medium, it is the space where Krumpholz breathes new life into their words.

It’s funny to think of 30 Miles of Crazy! as the logical progression point for an artist whose work used to be about the love lives of 20-something goths, which is what makes it exactly the type of work that Krumpholz should be doing. All artists start out wanting to tell their story, but once you’ve drained that well where do you go? For Krumpholz the answer is to tell other people’s story and in doing so he has reinvented himself as an artist. It’s a valuable lesson for creators of any age.

Karl Christian Krumpholz (W/A) • Self-Published, $5.00

Review by Robin Enrico

[…] Robin Enrico writes about 30 MILES OF CRAZY! #5 – 6 by Karl Christian Krumpholz, writing that in these issues, Krumpholz “demonstrates not only a […]