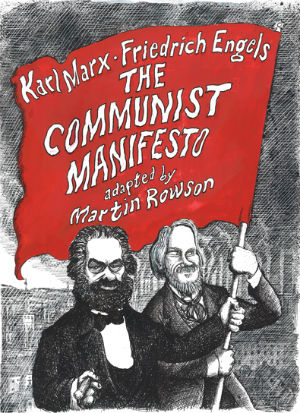

Communism is back baby. It’s good again. Awoouu (wolf howl). It may still be a dirty word to those on the right and centre, but a century after the October revolution partially inspired by the writing of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, there’s a resurgent left wing speaking openly about socialist policies and politics that’s also (almost0 perfectly timed for the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth.

Heck, even comics creators have been discussing the possibility of unionising again, something which would surely benefit the famously precarious profession and yet hasn’t been seriously considered since, I don’t know, the Sixties? (The creators-first formation of Image Comics in the Nineties, further espoused by bad small press comics men like Dave Sim and Brandon Graham, had a more Randian, libertarian, individualist bent). It is this anniversary, uptick of interest in his ideas, and the centuries of intervening history informed by his most seminal text which haunts Martin Rowson’s comic adaptation of Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto.

Heck, even comics creators have been discussing the possibility of unionising again, something which would surely benefit the famously precarious profession and yet hasn’t been seriously considered since, I don’t know, the Sixties? (The creators-first formation of Image Comics in the Nineties, further espoused by bad small press comics men like Dave Sim and Brandon Graham, had a more Randian, libertarian, individualist bent). It is this anniversary, uptick of interest in his ideas, and the centuries of intervening history informed by his most seminal text which haunts Martin Rowson’s comic adaptation of Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto.

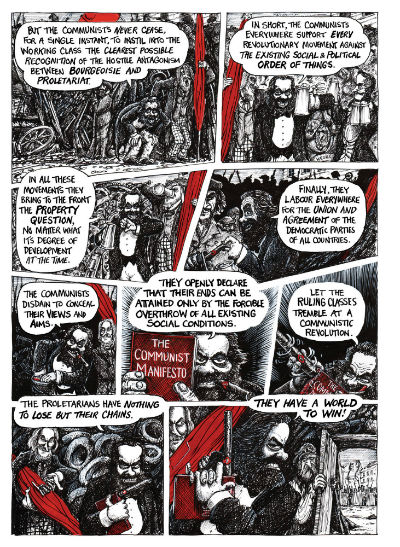

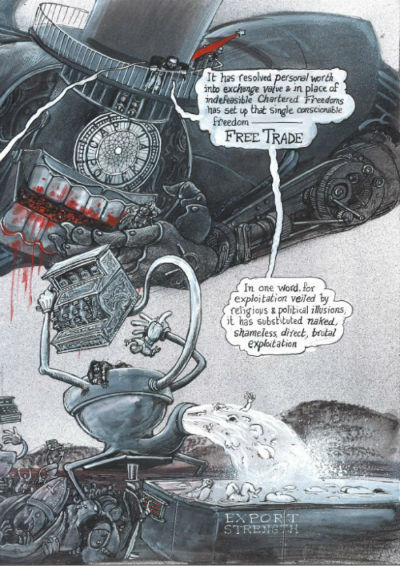

Besides all the nice drawings and that, historical perspective is the principal thing Rowson brings in the adapting. As he notes in his introduction, “history has failed to unfold precisely as Marx either hoped or prophesied, though it’s not Marx’s fault that in most revolutions the battering ram aimed against the walls of the elite always end up buckling at the last minute, ending up buttressing the even higher walls of the new elites.” At the end of the book, after completing the published text of the Manifesto, Rowson illustrates what came after. Symbolic statues of Marx and Engels are left to deteriorate before being felled to make way for a repressive state power whose allegiance to the markets — represented by walking toilets with screens depicting stocks rising and falling, their bowls alternately full of money and shit — that could stand in for Western and Soviet powers of the late 20th and early 21st century alike.

Before that: his cartoon Marx, with a Cheshire cat grin on his face while he leans conspiratorially towards the reader at the bottom of successive double page spreads, notes that the zeal with which the powers of old Europe brand their opposition as communists thus proves the very power of communism. At the same time, Rowson ironically deploys the iconography of anti-Soviet propaganda to make the exact opposite point those in power hoped to by depicting Marxism as a nightmarish dystopia.

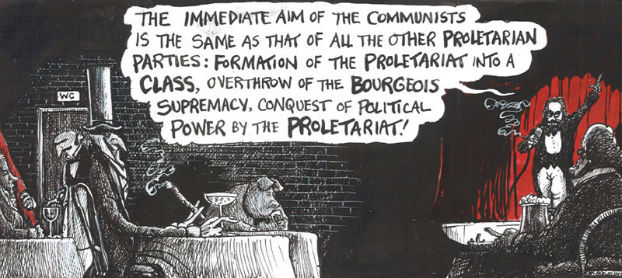

Serfs chained to the hamster wheel of indudtrialised labour, sweating blood, is an image here not of the Soviet workforce, but the system of labour the Manifesto implores workers of the world to unite and rise up against. When Marx and Engels lead the working men of all countries into battle at the end of the book, wielding copies of Das Kapital and the Manifesto as their weapons, it’s copping to the awesome power those texts wield.

Rowson also borrows the aesthetics of such propaganda to effectively illustrate the inescapable nightmare The Communist Manifesto makes life under a privileged ruling elite out to be. Capitalism is variously personified as a top hat-wearing Iron Giant tearing down old buildings to build factories, picking people up and throwing them into an industrial-sized mincer before the pulped mass of flesh is spat out into a “Surplus Value Villa,” as a fleet of flying pigs, and as a monocle-wearing bourgeoisie gleefully drowning labourers in market-won currency.

When I first flicked through a copy of Rowson’s book, I was worried he was deploying the anti-communist style unironically; that he instead does so in pursuit of a (mostly) pro-communist point of view is both a personal relief and canny artistic flourish. I know his work from his editorial illustrations in The Guardian, where he’s always halfway between the contemporary anarchy of peer Steve Bell and the didactic ink splatters of 19th century satirical cartooning, but his work has also appeared regularly in The Morning Star. To complete his bonafides, in his foreword Rowson talks about how upon reading the Manifesto as a 16-year-old, “it made complete and immediate sense.”

He also predicts that a significant number of self-described Marxists will “hate this book,” in part due to the broad spread of the “Marxist diaspora [which] encompasses everyone from former Trot Ayn Randists…to things as worryingly weird as… wizened old Maoists,” but also because there are implicit critiques of the source material in his Ralph Steadman-like drawings.

Marx decries the way capitalism reduces labourers to a commodity, yet throughout speaks of the proletariat in the same dehumanising terms as the bourgeoisie do. Accordingly, Rowson illustrates Marx — who is nominally addressing the world’s workers — as distant from them on the page as the murderous means of production that stamp on them and grind them to paste. The underclass are uniformly found under Marx, too, squashed at the bottom of the page. On almost every page they are shown being put through another Bosch-indebted torture, whipped by centurions and ground by gears and literally put through a wringer.

The pages where Rowson is faithful to the polemical spirit of the text are often the weakest, exposing the more literal (i.e. less artistic) side of satirical cartooning, as when the “collisions between the classes of Old Society” is illustrated as two steam-powered colossi scrapping in an arena, flanked by winged bourgeoisie holding plaques with things like “LAW,” “MORALITY” and “FAMILY VALUES.”

Above – Rowson at work on the book

Ultimately, his illustrated Communist Manifesto is neither the hatchet job nor hagiography I feared. It is certainly a left-leaning socialist comic, but one which gives as much time to critiquing capitalism as it does to Marxism itself, one which both subverts and in some way reinforces classic Western fears of communism by deploying familiar imagery, and one which acknowledges in its final pages that there is still a spectre haunting Europe.

The book ends with a mostly-wordless epilogue of Rowson’s invention, the double-page spreads reduced to single pages with constrictive white borders. The possibility of communism is replaced the dehumanising neoliberal present where, once again, iconography associated with the USSR — prison camps, chilly white climate, repressive police state — is repurposed as our current society, in thrall to banks and Silicon Valley, more unequal than ever.

A last bleak image has the rich at the top, enshrined in barbed wire and tossing champagne off a balcony onto the grimy slums below. In this context, the first words of the Manifesto leak out of what could be a rusted pipe, but could just as easily pass for spilled entrails, suggesting they — and this updated, accessible adaptation of his Manifesto — might inspire revolt yet.

Martin Rowson (W/A) • SelfMadeHero, £12.99/$19.99

Review by Tom Baker