One of the best things about the first and second issues of Live/Work by Pat Palermo is that they feel like comics from a different era, specifically the early 2000s. It’s a factor that greatly adds to the way in which Palermo portrays the experience of being a broke New York City creative around that same time period. While the story is an Altman-esque caper centered around the lives of a small group of twenty-somethings on the periphery of the New York fine art scene, it is Palermo’s ability to capture all the tiny points of verisimilitude of that time, that place, and those roles, that make it shine. That era, for all of the cartoonists who lived in the city at that time, is rarely represented in the medium. With his keen sense of character and precise naturalistic style that recalls both Scott McCloud and Dylan Horrocks, Palermo has created perhaps the most pitch perfect representation of that time, place, and life.

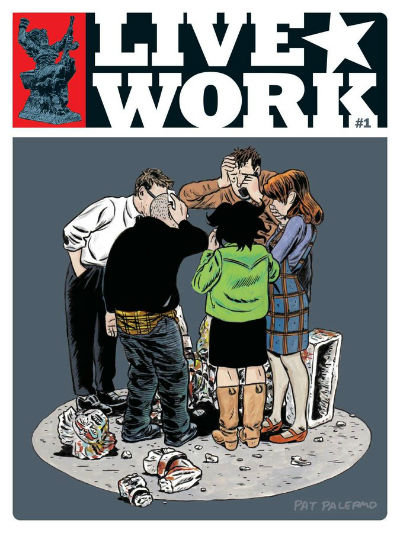

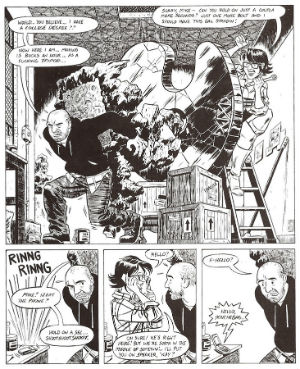

The two central threads pushing the action forward in Live/Work are the perpetual New York experience of needing to find an affordable apartment, and the sitcom-style search for the story’s bizarre McGuffin. In the case of the latter, a replacement for a life-sized statue of public domain Soviet superhero sex bomb Octobriana that broke off a larger sculpture by famous gallery artist Martha Ratzinger. This new statue of Octobriana will be chased after by an ad hoc Scooby Doo gang including: Martha’s kitsch finder Richard, her frazzled assistant Abby, gallery receptionist Veronica, and surly art handler Mike. All are satellites around the larger art world force that is Ratzinger, all aspiring artists in their own right, all eventual roommates in search of the titular live/work space.

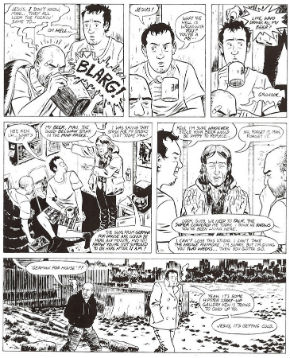

In between the various schemes to replace the statue, Palermo lets the reader hang out with our bumbling gang as they hang out with each other. These scenes are keenly observant of the New York milieu; be it bonding over being a big city transplant, having a serious conversation about your life while waiting for the subway, or smoking and grilling on a rooftop while watching fireworks. We are given further characterization when we see our protagonists showing their art to one another. In the kind of critique that could only come from a place of deep empathy, Palermo highlights the somewhat amateur nature of their creations. Abby’s twined paintings rely on salvaging other artist paintings, Veronica’s movie posters for movies of the near future are more clever than insightful, Ben’s comic murals on condemned buildings have the wit of a webcomic from that era, while Ben’s only artistic pursuit is painting endless portraits of a woman he is in love with from the internet.

The paper thinness of the gang’s art makes sense in the light of Ratzinger’s shallow recontextualization of the Octobriana statue and her later pile of garbage bags capped with a kitschy Buddha figurine. The aspiring protagonists are naïve and uninformed when it comes to art-making, likely following Martha’s cynical lead. Palermo’s real critique here is for those who exploit the labor of others for their own gain. In trying to secure a second statue of Octobriana Richard has a run-in with the disheveled original sculptor who is incensed that Ratzinger has used his work to turn a profit in the hundreds of thousands. While it is Richard who catches the apple in the face, the reader is keenly aware of how much that apple is directed at Martha. In a subtly elegant bit of parallel plotting, Palermo also includes the story of Pastor Omar who has been fleecing his parishioners to finance his gambling addiction. Though his story never intersects with that of the gang’s quest for Octobriana, his having to flee town after his bookie’s daughter threatens to let his parishioners know where their money is being spent results in our protagonist finally finding an apartment.

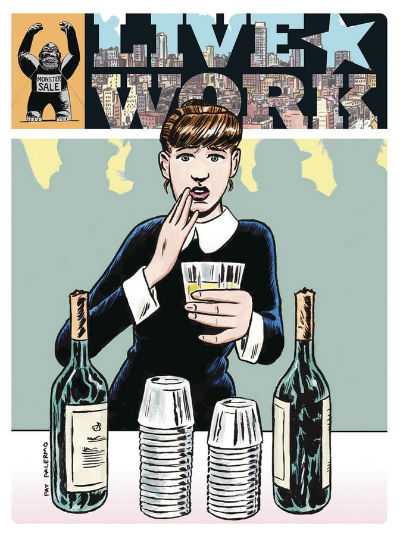

While Pastor Omar leaves his place trashed in hopes of throwing of his creditors, the protagonists still jump at the chance to live there. For just as important as their search for Octobriana and their artistic identities is their search for an affordable apartment. Palermo wrings a lot of comedy out of their mad scramble to find a place within their budget that will also facilitate their art making in an ever-gentrifying city. An early lead becomes a bust when it is revealed that a squatter is living in the back yard, another potential apartment is next to the borough’s largest slaughter house, a third is a basement with no shower or kitchen. So even though their new place is next to the car lot with the giant inflatable gorilla it comes as a godsend. At least they’ve found one of the things they have been looking for.

Beneath these more tangible searches is an even deeper one for happiness. For Veronica, her desire to be approved of by her artistic elders has her dating an older dilettante artist. But in seeking Ratzinger’s approval Veronica strikes out to find her own apartment and studio when confronted with the question of whether she wants to be an artist or an artist’s girlfriend. In the second issue Abby is torn between her old college flame Clytie and her girlfriend Frankie who is currently halfway across the world. Abby misses the way Frankie has helped her keep it together, but their long distance phone call also suggest that Frankie has been trying to open up their relationship to other partners. Given the stress of the Octobriana hunt, it is unsurprising that Abby takes Frankie up on the suggestion and sleeps with Clytie at the end of an especially hard day. After securing the long sought for apartment Ben leaves Mike in the lurch to run off to France to be with his Internet girlfriend and a chance at love. Perhaps the only thing more valuable than New York real estate.

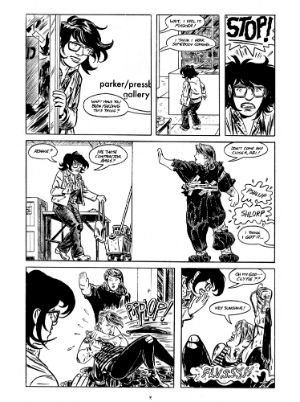

All of these small dramas and human comedies come together seamlessly through Palermo’s high-level draftsmanship. His mixture of detailed line work, and scratchy hatching from both pen and brush creates a look akin to a looser Jaime Hernandez or a denser Craig Thompson. His backgrounds are lush, detailed, and present in the majority of panels; giving a consistently strong sense of place and atmosphere. The characters come to life through their never over-exaggerated but always animatedly in motion body language and facial performance. Palermo’s pacing is also excellently controlled with a constantly moving camera that always seems to pick the perfect angle and moment. That he manages to fit multiple talky word balloons into a panel yet never have the composition feel cramped or even overly wordy is a testament to what a high level of cartooning he is working at.

These two issues of Live/Work are the perfect short story of young people at the time of peak chaos and excitement in their lives in New York City. If you are living or have lived that moment you recognize yourself in the trials and tribulations of these aspiring artists. Even if you haven’t their persistence in the face of all the obstacles life throws at them makes them endearing, faults and all. In a year full of strong debuts this is one of the strongest. Palermo is an accomplished cartoonist whose storytelling is confident and effecting. But most impressive is that the reader comes away from these two issues with the same level of empathy for the characters and their world as Palermo has for them.

Pat Palermo (W/A) • Adhouse Books, $6.00

Review by Robin Enrico