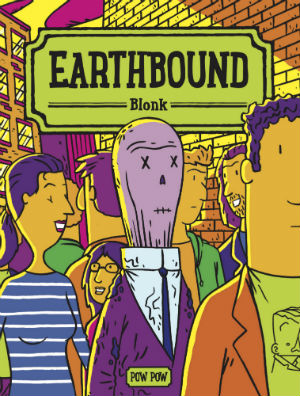

Earthbound by Jean-Claude Aumais (aka Blonk) is the kind of comic that ends up being more than the sum of its parts. Blonk takes the Twilight Zone-esque premise of a man unexpectedly returning from the dead and uses it as a form of hyperbole to dig into what it means to keep going after a disaster. For the protagonist of Earthbound being undead might unmoor you from the social contacts of the living, but you are still as chained to your past as anyone else. The book’s grounded approach to its fantastical premise, along with its uncluttered straightforward cartooning, lets the character’s interactions take the forefront, allowing the reader to ponder their actions and motivations as they try to sort out their lives and un-lives.

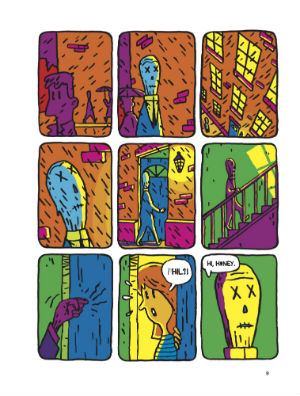

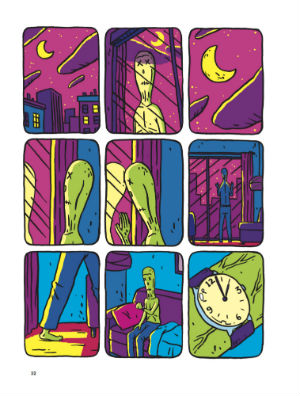

The tone of Earthbound is set nicely from the beginning when the zombified Phil rises from his grave and casually walks out of the cemetery. His blank expression as a bird lands on his head, combined with the electric blue and yellow coloring, cueing the reader into the off-kilter graveyard humor that’s to come. Equally important is the scene that follows wherein Phil returns to his ex-fiancé’s apartment and ends up frustrated to find that she has moved on with her life in the nine months that he has been gone. Phil is unable to understand that the world has continued on without him in it and can only process his time in the ground as a minor absence. Yet what else can he do? Where else would he go?

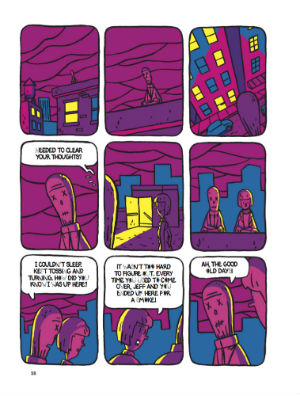

That people don’t run screaming in terror from the walking corpse that Phil has become is both part of the comedy of Earthbound but also the key to its deeper messages. Blonk subverts all of the classic zombie tropes by making the return from the grave more of a problem for the undead than the living. After his former fiancé rejects Phil, he has nowhere to go and ends up sleeping on a park bench only to be offered shelter and solace by a minister who mistakes him for a derelict. This is moment is played for laughs, but the fact remains that Phil has lost all connection to the life he once knew. Though not seemingly a metaphor for any specific tragedy, Phil’s return to the world of the living could parallel many people’s re-entering the world after a dark period in their lives.

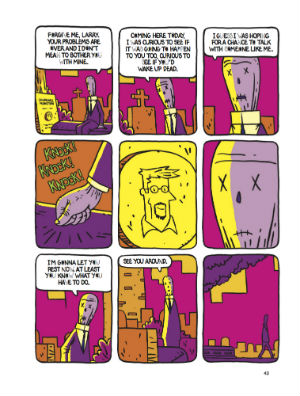

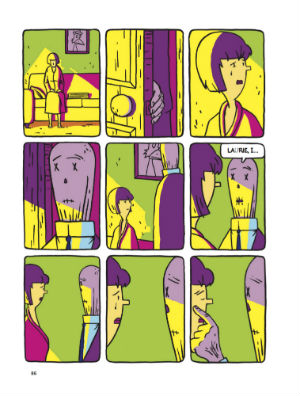

With nowhere else to go and no one else to turn to, Phil is fortunate to find both a friend and a place to stay in mild-mannered comic book store owner Jeff. The moment of zombified Phil and superhero-costumed Jeff reuniting and rekindling their friendship is ridiculous in its packaging but deeply human in its dialogue. The longstanding friendship between the two shines through as Jeff is certainly not going to let a little thing like Phil being a zombie get in the way of picking up right where they left off. Jeff’s live-in girlfriend Laurie is significantly less enthusiastic about Jeff bringing home his undead friend to crash on their couch in a way that again recalls less supernatural scenarios. Phil is everyone who has been down on his luck and had to rely on the good fortunes of their friends whose lives are more together. Somewhere between pitiable and a burden, he is a disruption in the comfortable life Jeff and Laurie have built together.

Phil is more than just an unwanted guest as it soon becomes clear that his unresolved past with Laurie may be what brought him back from the grave. In another interesting subversion, when Phil goes to the funeral of his recently deceased friend instead of feeling fortunate that he has returned from the dead he feels survivor’s guilt that he has been granted a second chance and Larry has not. More than that, he realizes that the complications of Larry’s life are at least over. Phil’s return may be a chance to square any unfinished business from his former life, but those problems have only become more complicated than when he departed. In still living after his life has collapsed, Phil has to face the repercussions of not only his absence, but also his actions before then. His neglect of his friendship with Larry and his romance with Laurie still haunt him even after he has become a ghoul.

The middle section of the book unfortunately verges more into melodrama than the subtler opening act. In a sequence that feels a bit too contrived, we see Phil’s desire to fully live his un-life renewed after a young woman is hit by a truck directly following her meet-cute with him. In a conversation that wouldn’t past the Bechdel test, Laurie confesses to her co-worker that she had cheated on Jeff with Phil before he died. It feels stock when the two women debate the difference between the comfortable life represented by Jeff and the exciting one represented by Phil. Later when Laurie gets upset at Jeff for getting injured in an attempted mugging, it almost feels like Blonk is trying to gin up the drama instead of letting it play out naturally as it did in the first section. Perhaps the biggest failing here is that the comedy derived from Phil being undead fades into the background when it was this over exaggeration that made similar earlier scenes off-kilter in a way that allowed for deeper meaning. As interpersonal drama the events feel far too familiar, where interpersonal drama with a walking corpse felt fresh.

The book’s finale however is a return to form for Blonk. All the tension between the story’s central characters explodes in moments that regain that perfect balance between the emotionally dramatic and supernaturally off-kilter. Phil’s status as a walking dead man adding a level of absurdity to the story’s love triangle, allowing the reader to take them at more than face value. Yet in a final set of subversions neither Jeff nor Phil are actually mature enough to deal with the complexities of the situation the have gotten themselves into. With one trying to escape by fleeing town to travel the world and the other donning super-hero garb and seeking an equally selfish escape from his problems. This inability by both men to realize that they need to face that the world moves on with out you is highlighted by the book’s somber coda where Phil’s un-life has come almost full circle back to the moment when he crawled out of the grave at the beginning.

For what Phil didn’t learned from his experience is that clinging to the past is an unwinnable scenario. Despite multiple opportunities to reshape his life anew he continues to tread water so that while on the surface he might have appeared to be more adventurous than Jeff, at the end of the day he is just a much a prisoner of his own nostalgia. It makes an earlier comment from Laurie’s co-worker about her own undead ex-boyfriend who purposelessly hung around her apartment for two years all the more prescient. Though she is at times portrayed as a scold, Laurie is the only character able to continually move forward. By the end of the story the reader realizes that her frustration with the pathetic men in her life has as been completely justified. Living or undead they have all been unable to create purpose in their lives outside of being with a woman and keep projecting this insecurity on to her.

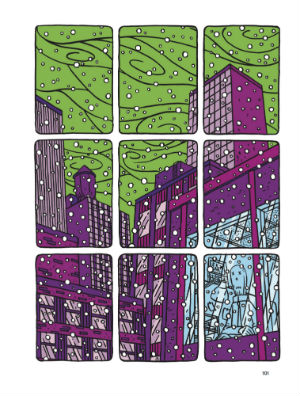

What is striking is that when Blonk is nailing the beats of his story the reader becomes so invested that it becomes easy to overlook some of his aesthetic limitations. The consistent nine panel grid works wonders at keeping the plot moving along at a brisk pace. Though he relies a heavily on above-the-shoulder facial close-ups for many of his panel compositions, when the dialogue is clicking they do an adequate job at conveying the emotion of the scene. His rare atmospheric wide shots, splash pages and cutaways always stand out and function as compelling images even outside of the context of the scene they are in. Perhaps the interjection of a few of these expressionistic panels in the melodramatic scenes might have helped sell the drama more than the stagey presentation he employs. A special note must be given to the color, which is absolutely sings in its willingness to be as impossible as the dead returning to life. Blonk’s orange sunsets cast light onto purple trees and yellow grass, while his orange clouds and magenta buildings breakup a pale green sky. In eschewing representation over vibrancy with his coloring, he makes the world he has created shimmer with energy and life.

Earthbound is a good first graphic novel for Blonk. If some sections don’t fully land, the ones that do hit their mark so strongly. He gives the reader some memorable moments and a conclusion to really chew on. As a cartoonist he shows himself fully capable of telling a complex story within his simplified style, occasionally showcasing his ability to create gorgeous mood-rich images. It is many of those strong silent panels that linger with the reader, where by simply observing these characters and their world we feel a part of them. By leaning even further into the things he does well here his work can only become more affecting and resonant.

Blonk (W/A) • Pow Pow Press $24.95

Review by Robin Enrico