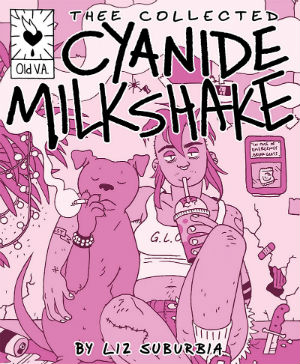

Powerful as any given issue of a minicomic can be there is a certain weight to having a larger collection of an artist’s work. With the thicker spine comes not only the added perception of a more substantial body of work, but being able to read several years of an artist’s creative output in one sitting creates room to reflect on just how much they have grown as a creator. Thee Collected Cyanide Milkshake by Liz Suburbia collects seven issues of the titular series in a nicely digestible format that, on deeper reading, serves as a document of Suburbia’s artistic and personal development. Though the work is only occasionally autobiographical, the shifts in Suburbia’s narrative and aesthetic choices are often just as revealing as the sections in which she directly addresses the audience.

Powerful as any given issue of a minicomic can be there is a certain weight to having a larger collection of an artist’s work. With the thicker spine comes not only the added perception of a more substantial body of work, but being able to read several years of an artist’s creative output in one sitting creates room to reflect on just how much they have grown as a creator. Thee Collected Cyanide Milkshake by Liz Suburbia collects seven issues of the titular series in a nicely digestible format that, on deeper reading, serves as a document of Suburbia’s artistic and personal development. Though the work is only occasionally autobiographical, the shifts in Suburbia’s narrative and aesthetic choices are often just as revealing as the sections in which she directly addresses the audience.

Few collections ever present a perfect record of an artist’s development as there is always material edited out or left on the cutting room floor. In place of the first issue of Cyanide Milkshake, Suburbia opens this collection with a preface explaining the reasons why it was not included. It’s a story that any cartoonist reading will know all too well. Not only is she now mortified at the content of the issue, even drawing the second issue a few years later she maintained nothing of the first issue’s visual style. When she expresses that she hopes that the handful of punks she gave copies of the first issue to outside a show used theirs as toilet paper the completist reader may wince. But the cartoonist who has also shared this experience of artistically maturing in the public eye breathes a sigh of relief. That Suburbia prefaces the collection in this manner is a good reminder that part of the reason for collecting older work is to demystify the journey of the artist. Creating comics that you couldn’t bear to let anyone to read years later is all part of the process of getting to place where you can create better work.

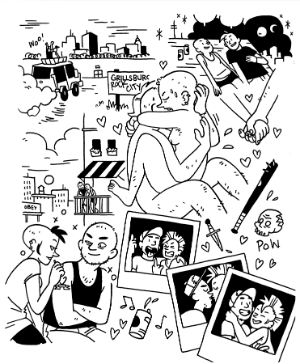

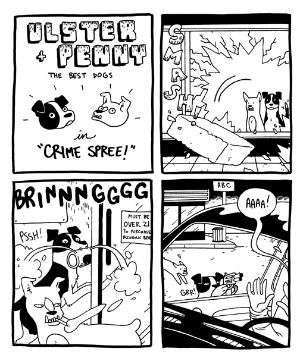

Meanwhile, the issues that are present in Thee Collected Cyanide Milkshake can best be described as a structurally freeform hodgepodge of various short comics that all hang together thanks to Suburbia’s signature aesthetic and theming. The pages of Cyanide Milkshake contain fake exploitation movie advertisements, funny animal goof-‘em-ups, autobiographical pieces, a guide to making ramen, sexy pin-ups, super-hero parodies, and a serialized post-apocalyptic erotic gag comic. Almost all are conjured with a bawdy and spirited sense of humor, as Suburbia is never one to shy away from a good bodily functions joke. In a one-pager about trying to learn how to urinate standing up as a woman, the punchline is her roommates returning to a spotlessly cleaned bathroom. For Suburbia the body is both lovably ridiculous and potently majestic. There is a joy in her drawings of body hair, be it punk rockers with pubic hair spilling out of their pants or Princess Mononoke–esque feral women whose wild locks cascade out from beneath wolf furs. Equally joyous are the fictional misadventures of her dogs Penny and Ulster as they drink at a bar, mosh at a concert, commit crimes, and bite big-eyed aliens. Though early drafts of Suburbia’s graphic novel Sacred Heart appear in the pages of Cyanide Milkshake, it appears that the latter was a place to cut loose, be gross, and have fun away from the heavier tone of the former.

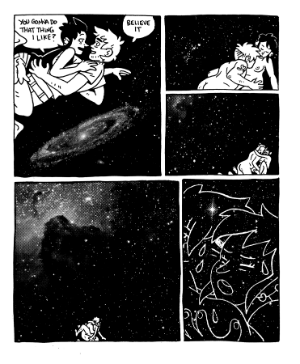

The clearest distillation of what Suburbia wants to do with Cyanide Milkshake comes in the form of the serialized post-apocalyptic erotic Boy Girl Adventure comic that anchors each issue. Surrounded by zombies and a myriad of other dangers, bumbling wasteland punks Bruce Barefoot and Kimberly Phister are busy trying to figure out their romantic boundaries. With the heightened danger and nearness of oblivion continually goading this dirty pair into sexual congress. Though almost a graphic novel in and of itself, Boy Girl Adventure is thematically of a piece with the rest of Cyanide Milkshake. All of Bruce and Kimberly’s adventures functioning as impetus to get them back to taking joy in the meshing of their bodies. The couple’s lovemaking is depicted at times as tender, other times as times comical, but always as the reason why they both are willing to do what it takes to survive. So that when they eventually transcend earth and fly off into space, Suburbia renders their final union as a celestial event. It’s an amazing trajectory for what might have begun as a joke comic about sex at the end of the world.

This more heartfelt ending is Bruce and Kimberly feels in keeping with Suburbia’s own journey during the making of Cyanide Milkshake. Near the end there is a short comic in which she discusses how she feels broken and exhausted after completing Sacred Heart. It is striking what a radical change this is from the DIY never-give-up energy espoused in her introductions to the in early issues. Yet over the course of the series’ seven-issue run Suburbia’s letters to the reader slowly transitioned away from punk rock screeds to more philosophical essays. Gag strips start to disappear as more and more autobiographical ones slip in to take their place. Her sex and fart jokes give way to more emotional moments such as the conclusion of Boy Girl Adventure or the final Penny and Ulster appearance being an ode to the simplicity and joy of a dog’s understanding of the world. By the end of the series Suburbia has finally been able to put words to thing she had been exploring all along. The best joys are the simplest ones and often the physical ones. The world is to be experienced in the moment together with all our other fellow animals.

The less noticeable change over the course of the series is the way in which Suburbia alters her visual style. While the second issue has a slightly more realistic look to its characters, this is dropped but the third issue in favor of a more cartoony style with a much thicker line, one she maintains for the rest of the run. Suburbia’s switch to using sharpie markers on copy paper for line work gives it a much lively feel, and likely allowed her to more easily balance her compositions with huge patches of black. Though her figures are rendered simply Suburbia employs little patches of cross-hatching that do the heavy lifting of texture and shadow with precision. Even with her low detail presentation she consistently draws some form of setting into her panels, and when called for she is easily able to pull off a crowd that feels like it’s made up of a group of individuals or a rendering of the Washington DC Metro that accurately captures the idiosyncrasies of that space. There is just something about Suburbia’s art here that in combination with the content projects the sense that she enjoyed drawing it, doing much to let the reader know to enjoy themselves as well.

The less noticeable change over the course of the series is the way in which Suburbia alters her visual style. While the second issue has a slightly more realistic look to its characters, this is dropped but the third issue in favor of a more cartoony style with a much thicker line, one she maintains for the rest of the run. Suburbia’s switch to using sharpie markers on copy paper for line work gives it a much lively feel, and likely allowed her to more easily balance her compositions with huge patches of black. Though her figures are rendered simply Suburbia employs little patches of cross-hatching that do the heavy lifting of texture and shadow with precision. Even with her low detail presentation she consistently draws some form of setting into her panels, and when called for she is easily able to pull off a crowd that feels like it’s made up of a group of individuals or a rendering of the Washington DC Metro that accurately captures the idiosyncrasies of that space. There is just something about Suburbia’s art here that in combination with the content projects the sense that she enjoyed drawing it, doing much to let the reader know to enjoy themselves as well.

While the individual issues of Cyanide Milkshake have long been something for indie comics convention-goers to look forward to, it is a boon to the larger comics reading public to have them collected. Thee Collected Cyanide Milkshake is the perfect introduction to what makes Suburbia such a vital artist. A coming-of-age story both on and between the pages and a testament to Suburbia’s work as an artist, the book is both hilarious and sincere. It brings the reader as close to her characters as they do to Suburbia herself, and hopefully as inspired to take the same journey.

Liz Suburbia (W/A) • Gimme Action $19.95

Review by Robin Enrico