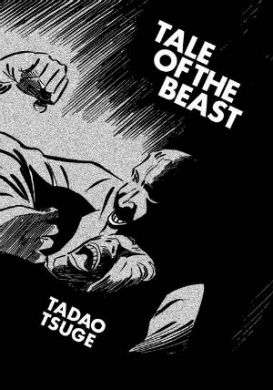

On a dark and stormy night in late December, a hooded stranger pulls into one of Tokyo’s struggling dive bars. He convinces its ageing female custodian to give him a place to stay and a bed to share. A few streets over, the bludgeoned body of a local pharmaceuticals employee, and the half-million yen Christmas bonus he’d just left work with, is discovered by a couple of inebriated lovers. Thus is the setup to Tadao Tsuge’s Tale of the Beast – a hardboiled proletarian crime noir from the cult mangaka who brought us Slum Wolf and Trash Market – now printed for the first time in English since its original publication in 1987.

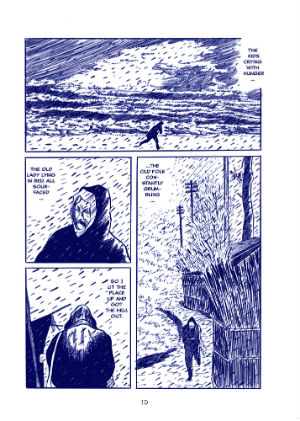

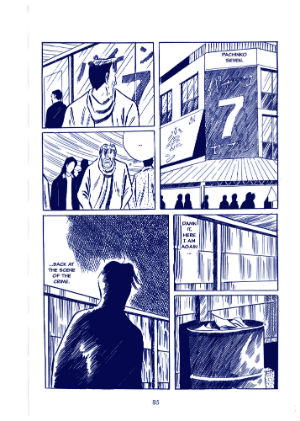

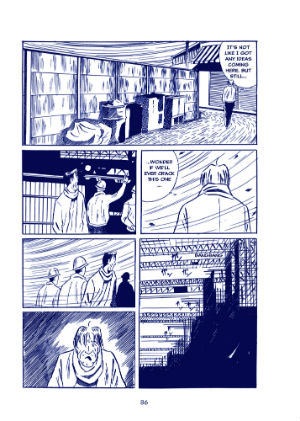

With its guilty party identified from the outset, Tale of the Beast‘s heart lays more in a philosophy than a whodunit narrative. Whether intentional or otherwise, this favouring of ideas over action is felicitous, since, unbeknownst to Tsuge at the time, the magazine in which it was serialised would fold before its completion. On one hand, the panels that Tsuge did put to paper could be read as scene setting for a story that never really takes off. Yet Tale of the Beast‘s incomplete form in many ways complements its message. The Japanese working class experience that Tsuge presents is one of loose ends; characters striving for and then losing all hope of an imagined satisfaction that only exists in the movies. Plot development is slow and subtle, with the reader catching shards of information from an intimate whisper, a curse muttered into the wind, or an overheard news bulletin. Movement takes place in the shadows, and silent, abstract panels illuminate individuals amid street crowds, their wearied faces contorted in grief or ecstasy. Settings are transient, and those who populate them rootless, making a murder case with seemingly no motive all the more impossible for a jaded detective to crack. Almost by accident, a narrative begins to emerge, with nihilistic construction worker Kiyohiko Ogura at its centre.

Distinguished by his glassy eyes and maniacal laugh, Ogura targets white collar victims for sums of money that bring him minimal economic or social advantage. His own life being of little value to him, he easily dispenses with those of others, claiming to have no choice or control over his actions. If any motivation can be attributed to Ogura’s character, his frenzied violence strikes as a bid to claw some limited sense of power from the middle classes, or as an attempt to feel something – anything – after a post-war childhood of poverty and abuse has left him “empty, like a shell.” The hostess who ditches her residence and employment to join him on the lam is equally numb, achieving none of the intimacy or excitement she might have half-heartedly expected from their Bonnie & Clyde-style adventure. Her attempts to break free from her existence succeed only in setting her on a different path to disappointment and despair.

Together the fugitive couple leaves no leads for the exasperated detective heading the investigation, whose worldview becomes just as hopeless as theirs. “There’s people gettin’ whacked every day. No one gives a damn no more,” he laments as the endless news cycle of murder and brutality steamrolls ahead while his case remains cold. Shared anxieties of apathy and impotence haunt both criminal and law enforcer, along with a mutual disdain for the contented masses; “idiots” and “mugs” who drink and spend instead of giving a thought to issues of morality and mortality. “They don’t think about nothin’ … They only care about havin’ a good time.” The characters’ feelings of madness and frustration at an individual and institutional level find no resolution, with Tsuge self-consciously setting them on a doomed search for meaning as if to prove there is none to be found.

Together the fugitive couple leaves no leads for the exasperated detective heading the investigation, whose worldview becomes just as hopeless as theirs. “There’s people gettin’ whacked every day. No one gives a damn no more,” he laments as the endless news cycle of murder and brutality steamrolls ahead while his case remains cold. Shared anxieties of apathy and impotence haunt both criminal and law enforcer, along with a mutual disdain for the contented masses; “idiots” and “mugs” who drink and spend instead of giving a thought to issues of morality and mortality. “They don’t think about nothin’ … They only care about havin’ a good time.” The characters’ feelings of madness and frustration at an individual and institutional level find no resolution, with Tsuge self-consciously setting them on a doomed search for meaning as if to prove there is none to be found.

In the absence of a tidy conclusion or a triumph of ‘good’ over ‘evil’, the main source of satisfaction within the world of Tale is in the glee Ogura derives from anarchy and disorder. He marvels at his own criminal and sexual exploits – which become increasingly depraved after each kill – and at the relative freedom afforded him by the big city, compared to his rural origins. “Seems you can get away with anything in this town,” he laughs to himself. Signing his name with an encircled capital ‘A’, Ogura signifies the chaos that threatens a despondent, desensitised generation that has grown up in the shadow of war, witnessing the PTSD and lost youth that plagues their parents, and responding with an attitude of reckless abandon. He is equally a symbol of proletarian retribution; the blood that is spilt when those who are comfortable and complacent are confronted by those who roam from town to town, hungry for food, work, and purpose.

Where a murder mystery relying on action, plot twists, and a binary tussle between right and wrong might now be long forgotten, Tale of the Beast’s narrative openness allows its reader to imprint contemporary concerns onto a skeptical worldview in which everyone is suspect and most are guilty (“These days you’ve got regular folks putting hardened criminals to shame with some of the things they do”). Non-prescriptive in message, Tsuge’s writing remains vital thirty years after its creation, even overlapping thematically with comics’ most timely breakout hit, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina.

Where a murder mystery relying on action, plot twists, and a binary tussle between right and wrong might now be long forgotten, Tale of the Beast’s narrative openness allows its reader to imprint contemporary concerns onto a skeptical worldview in which everyone is suspect and most are guilty (“These days you’ve got regular folks putting hardened criminals to shame with some of the things they do”). Non-prescriptive in message, Tsuge’s writing remains vital thirty years after its creation, even overlapping thematically with comics’ most timely breakout hit, Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina.

With a manga career spanning over 60 years, Tadao Tsuge’s work has appeared in the likes of Garo, Yagyoand Gento, but has so far been relatively unavailable to English-speaking audiences. Tale of the Beast provides a topical entry point to his world, unflinching and unromanticised in its scrutiny of the disenfranchised, yet nevertheless darkly beautiful in tone and visuals. This year will also see the collected works of his more widely known brother, Yoshiharu Tsuge, published for the first time in English by Drawn & Quarterly.

Tadao Tsuge (W/A) • Black Hook Press

Available to order online here

Review by Ally Russell