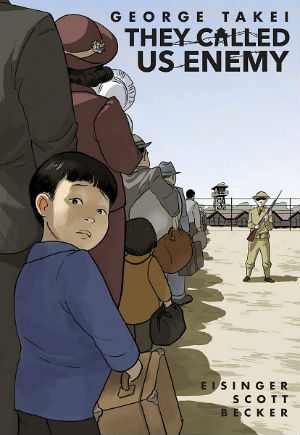

Legendary actor; LGBTQ+ advocate; community activist; social media influencer. As one of the most visible Japanese Americans in the public eye, George Takei has consistently used his platform to draw attention to urgent social issues. Now, with They Called Us Enemy via Top Shelf Productions, Takei adds graphic novelist to his resume, blending Japanese manga and American comics traditions to examine his own childhood experiences as a second generation immigrant growing up amid one of the most shameful, yet most overlooked, chapters in US history.

Working with co-writers Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, and artist Harmony Becker, Takei’s story begins in 1941; the year the United States declared war against Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. Responding to public and political pressure to “lock up the J*ps” (with vocal proponents including the Attorney General of California and the Mayor of Los Angeles), President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered in February 1942 that all persons of Japanese ancestry be “excluded” from certain areas of North America’s West Coast, which had by then been declared a military zone. The eldest of three children, George Takei was just four years old when his family – along with tens of thousands like them – was uprooted from their home in Los Angeles, California; made to abandon all their belongings beyond what they could carry; and forced to live in converted racetrack stables repurposed as an internment camp. George, his parents, and younger brother and sister were tagged by armed personnel, and made to build a new life in a cramped horse stall. There they would be treated as “alien enemies”, in the country his father had called home for the past quarter century.

Working with co-writers Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, and artist Harmony Becker, Takei’s story begins in 1941; the year the United States declared war against Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. Responding to public and political pressure to “lock up the J*ps” (with vocal proponents including the Attorney General of California and the Mayor of Los Angeles), President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered in February 1942 that all persons of Japanese ancestry be “excluded” from certain areas of North America’s West Coast, which had by then been declared a military zone. The eldest of three children, George Takei was just four years old when his family – along with tens of thousands like them – was uprooted from their home in Los Angeles, California; made to abandon all their belongings beyond what they could carry; and forced to live in converted racetrack stables repurposed as an internment camp. George, his parents, and younger brother and sister were tagged by armed personnel, and made to build a new life in a cramped horse stall. There they would be treated as “alien enemies”, in the country his father had called home for the past quarter century.

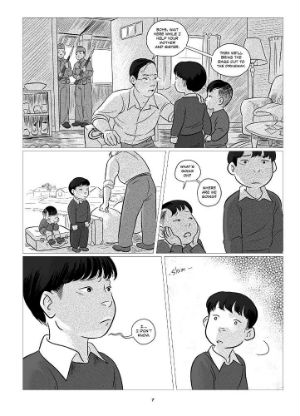

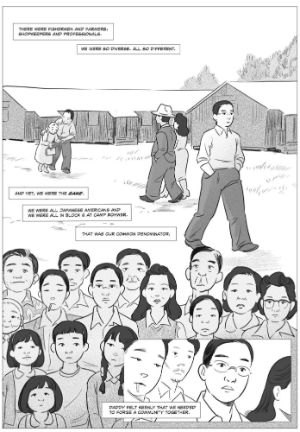

They Called Us Enemy depicts a turbulent upbringing spent in unimaginably dehumanising and degrading circumstances, as interpreted through a child’s naïve gaze. Hours spent on the hot, crowded trains transporting George and his family to each new internment camp seem to him a vacation. He and his playmates share fantasies that the barbed wire fences surrounding them are in place to keep out dinosaurs. Small moments, traumatic or tender, take on huge significance, as they are wont to do in childhood. Particularly formative to George are the nightly movies screened in the camp mess hall, where his imagination, and the power of film, are able to transport him from a harsh reality. Becker’s expressive linework makes emotions jump off the page, whether in wide-eyed wonder, determination, or embarrassment. Meanwhile, parents’ anxieties at having their hard won freedoms, assets, and dignity seized are successfully kept out of view from their children, lessening the impact of the devastating blows dealt by a callous, racist system. Somehow, thanks to the unwavering tenacity of his mother and father, young George manages to maintain his innocent outlook, where others in his position may not have.

Interspersed narration from a now adult Takei explores the nature of memory, and offers perspective afforded by hindsight. He shares his realisation that the incendiary words of a few men seeking political power can scapegoat a minority group overnight; that the seemingly innocuous wording of a President’s Executive Order can have ruinous effects on whole populations. He acknowledges the incredible strength it took for his father to hold steadfast to his belief in American democracy, in spite of the officially sanctioned crimes committed against his own rights and liberties. He appreciates the courage of his mother, who smuggled her sewing machine into each new camp; a forbidden effort to make a home for her family in a hostile environment.

Interspersed narration from a now adult Takei explores the nature of memory, and offers perspective afforded by hindsight. He shares his realisation that the incendiary words of a few men seeking political power can scapegoat a minority group overnight; that the seemingly innocuous wording of a President’s Executive Order can have ruinous effects on whole populations. He acknowledges the incredible strength it took for his father to hold steadfast to his belief in American democracy, in spite of the officially sanctioned crimes committed against his own rights and liberties. He appreciates the courage of his mother, who smuggled her sewing machine into each new camp; a forbidden effort to make a home for her family in a hostile environment.

By 1946, with the war over, we see the Takeis return to their native Los Angeles, where nothing remains of their former lives. Homeless, living on the streets, they almost find themselves yearning for the safety and routine of incarceration behind barbed wire; for that prison which had been their home for the past four years. Again, through the quiet determination of his mother, and the community activism of his father, we see how one family managed to build a new life out of nothing. It would still be forty years until the US Government would officially acknowledge its interment of over 120,000 Japanese Americans during the Second World War as wrongful.

The combined vantage points of George both past and present allows this graphic memoir to communicate complex issues simply and succinctly, and to present the universal through the personal, without diluting the nuance of its messages. For example, it wasn’t until he reached adulthood that George would come to terms with the misplaced shame and isolation that those subjected to the detainment would carry for the rest of their lives, haunted by a trauma which most refused to talk about once the war had ended. We see him as a fourth grader singled out by a prejudiced primary school teacher; “I was old enough by then to understand that camp was something like jail,” Takei narrates, “but could not fully grasp what we had done to be sent there.”

The combined vantage points of George both past and present allows this graphic memoir to communicate complex issues simply and succinctly, and to present the universal through the personal, without diluting the nuance of its messages. For example, it wasn’t until he reached adulthood that George would come to terms with the misplaced shame and isolation that those subjected to the detainment would carry for the rest of their lives, haunted by a trauma which most refused to talk about once the war had ended. We see him as a fourth grader singled out by a prejudiced primary school teacher; “I was old enough by then to understand that camp was something like jail,” Takei narrates, “but could not fully grasp what we had done to be sent there.”

Caught between two worlds and identities (an idea intrinsic to the book’s format, which reads from left to right in English, yet adopts a black and white manga visual style), Takei finds himself in a unique position from which to ask: Who gets to decide what it means to be American? His memories of his camp experience champion the diverse community of first, second and third generation Japanese Americans – all different, yet the same in the eyes of white America – who banded together to forge a community, building an inhabitable place for each other and their families. He celebrates not only the bravery of the interned, but also those supporting them from the outside, like the Quaker missionary committed to delivering books and personal items to internees on a weekly basis. To close, Takei quotes Barack Obama, stating that history “must be a manual for how to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.” The connections made to today’s American landscape of unlawful imprisonment, family separation, and immigration bans, though indirect, are undeniably poignant. By sharing his story, and thereby highlighting a largely unknown part of US history, Takei delivers a cautionary message, albeit one invested in hope, and the resilience of the human spirit.

George Takei, Justin Eisinger & Steven Scott (W), Harmony Becker (A) • Top Shelf Productions, $19.99

Review by Ally Russell

George Takei can next be seen in “The Terror: Infamy” – a horror-infused anthology series centred around a Japanese-American community during World War II – on which he also serves as a consultant.

The series premieres Monday October 7th at 21:00, exclusive to AMC UK.