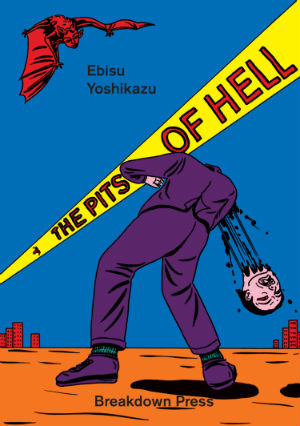

“Television star, father of three, professional gambler, writer, cartoonist, pioneer”. Add in mop rental salesman, and there reads the resumé of Ebisu Yoshikazu; the alternative mangaka whose raw, visceral and ever vital work is collected in new English language edition The Pits of Hell via Breakdown Press.

Originally published by the likes of Garo and Jam between 1969 – 1981, the nine proletarian nightmares comprising this new volume well represent the themes and visual style that established Ebisu as one of the leading figures of the ‘Heta-uma’ manga movement; translating to “bad-good”, and representing to Japan what New Wave meant to the French and Punk did to the British. Etched in an intentionally primitive, wonky style – Ebisu’s self-taught draftsmanship befitting the unskilled work settings at the centre of each tale – are absurdist visions of what can happen when tempers reach boiling point, and that which is repressed is allowed to surface. We see patronised labourers and put-upon salarymen pushed to their limits as they exact graphic, violent revenge on Ebisu’s image of capitalist hell; abusive employers, demanding wives and complaining children, coupled with rising food prices and falling wages. From adolescence to adulthood, school to employment, Ebisu’s male protagonists are treated like kids their whole lives, enslaved first to their parents and teachers, and then to bosses, romantic partners, and even machines (as seen through the arcade game in ‘Pachinko’).

Originally published by the likes of Garo and Jam between 1969 – 1981, the nine proletarian nightmares comprising this new volume well represent the themes and visual style that established Ebisu as one of the leading figures of the ‘Heta-uma’ manga movement; translating to “bad-good”, and representing to Japan what New Wave meant to the French and Punk did to the British. Etched in an intentionally primitive, wonky style – Ebisu’s self-taught draftsmanship befitting the unskilled work settings at the centre of each tale – are absurdist visions of what can happen when tempers reach boiling point, and that which is repressed is allowed to surface. We see patronised labourers and put-upon salarymen pushed to their limits as they exact graphic, violent revenge on Ebisu’s image of capitalist hell; abusive employers, demanding wives and complaining children, coupled with rising food prices and falling wages. From adolescence to adulthood, school to employment, Ebisu’s male protagonists are treated like kids their whole lives, enslaved first to their parents and teachers, and then to bosses, romantic partners, and even machines (as seen through the arcade game in ‘Pachinko’).

Working full time as a sign shop worker at the time of writing, Ebisu infuses his stories with potently personal resentments, while also speaking for the multitudes of fellow high-school-educated baby boomers who similarly moved from Japan’s agricultural regions to its big cities to take on unskilled work in the late ’60s and ’70s. These characters and their experiences will be familiar to readers of other golden age underground manga, such as the comedy of Fukutani Takashi, or the noir of Tsuge Tadao. Yet where his peers employed symbolic, allegorical devices to explore the issues of their generation, Ebisu’s work offers perhaps the most unfiltered portrait, as he takes down with unparalleled candidness and quite literal violence the neo-feudal structures and social injustices that coloured post-war Japan. Take ‘Workplace’, for example. The story follows a sign shop worker who is forced to endure the daily verbal, physical and psychological torment inflicted on him by his employer. The situation boils up slowly as the employee withstands insults, beatings, and is even made to gulp down the maggot infested food cast off by his boss, until a final slight pushes him to explode into a murderous rage. Such downtrodden blue-collar workers serve as unmasked conduits for Ebisu, who slays his tormentors through comics in a psychic bloodletting so forthright it chills.

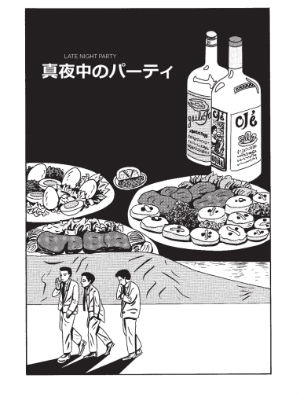

Men aren’t the only victims of the capitalist system, and Ebisu does give voice to the domestic abuses suffered by women and children – albeit at the hands of his protagonists (see ‘Wiped Out Workers’, ‘Battles Without Honor’, ‘Salaryman in Hell’). In many ways, The Pits of Hell prints Ebisu’s id on its pages for all to see. In the retrospective essay written in 2016 and included in this volume, the artist admits embarrassment at having to go back and read some of these stories now, having been just a few years out of high school at the time of their creation, with much to learn in the ways of maturity. These are certainly the more uncomfortable and potentially triggering moments to read for their sexual violence (‘Late Night Party’, ‘Tempest of Love’). Yet the ugliness of such dystopian visions are, disturbingly, not far from realities and attitudes that still persist in society today.

Like dreams and nightmares, the situations arrived at in The Pits of Hell are both believable and exaggerated to the point of absurdity, going hand in hand with the “fujōri” (meaning illogical, irrational) visual style which incorporates fantastical imagery such as UFOs hovering over herds of identical salarymen. A particular highlight comes in ‘ESP’, which observes the battle of psychic energies between gamblers desperately trying to influence the outcome of a boat race through telekinesis to make a few yen. Inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), specifically their depiction of a “slow shift into madness”, Ebisu’s work takes its place in a long legacy of surreal satire, energetically speculating on ideas of civilisation’s self-destruction and society reverting to savagery, which remains ever pertinent (see Bong Joon Ho’s feature film Parasite released this year). Alongside the aforementioned commentary by Ebisu himself, The Pits of Hell features a foreword by Minami Shinbō, and an essay from Ryan Holmberg.

Ebisu Yoshikazu (W/A), Ryan Holmberg (T) • Breakdown Press, £14.99

Review by Ally Russell