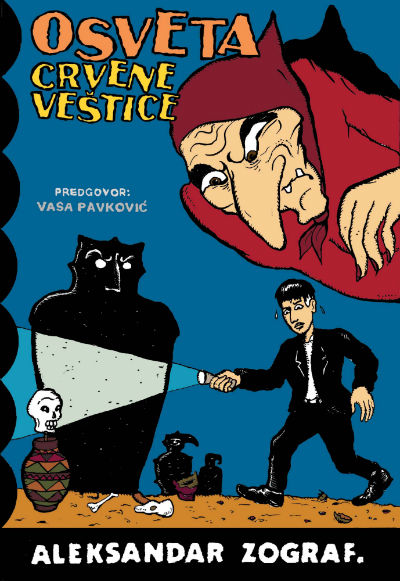

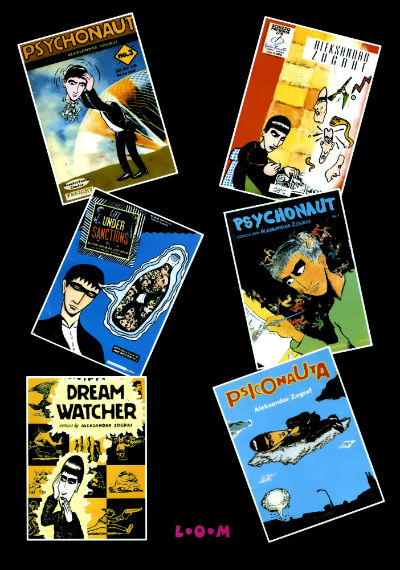

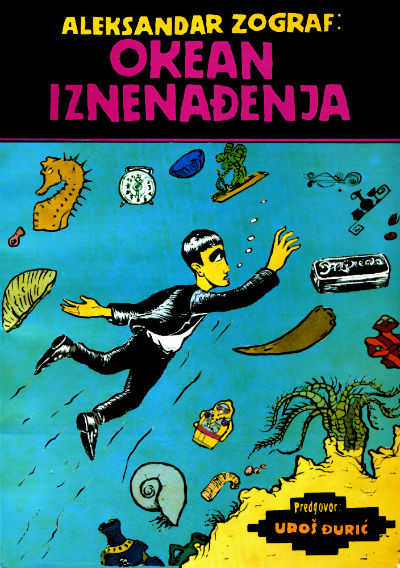

Aleksandar Zograf is an extremely distinctive figure in Serbian comics with a strong international reputation. Both poles of comic culture are combined within him – the alternative impulse and his love for comics traditions and the early comics. With such a creative aura he became famous, and has had work published by Fantagraphics, Kitchen Sink Press and Top Shelf Productions. There is also his “archaeological passion” for trivia. Any difference between the universal and local doesn’t exist for him. Whether at the Pancevo flea market or in a nearby village, or in some small Italian town, everywhere, he finds things that radiate some universal value to him, and at that moment “Sasha”’s meditation about the past and the present begins. As he would say, the flea market is a timeless adventure, an expression of the collective unconscious, like a museum of the human race or an amusement park.

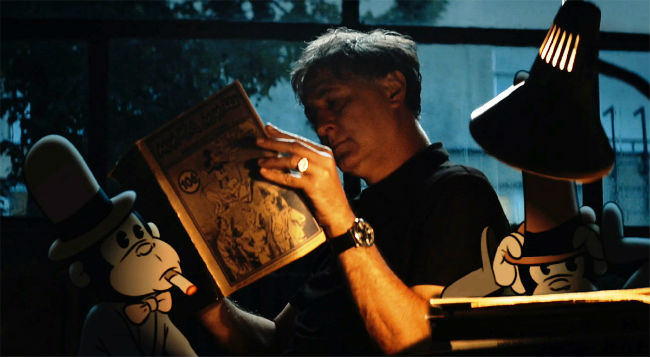

ZORAN DJUKANOVIC: Last year, a long feature documentary The Final Adventure of Kaktus Kid was released, and it started being screened at European film festivals. It features you, the Kaktus Kid, a prickly potted plant and the absent tragic hero. The movie is not easy to define. Is it a documentary, an animation, an investigation, a history of comics…?

ALEKSANDAR ZOGRAF: The film is actually a hybrid. It is first of all a documentary, but there are parts which are live action with a set of actors, and there is animation too. It touches the little known (outside this part of Europe) history of Serbian comics, which was very productive in the 1930s. Also, it speaks about the power of drawing, and its ability to provoke strong reactions. But it also is the search for information about Veljko Kockar, a largely forgotten cartoonist from Belgrade, whose death was put under the carpet for many decades.

Finally, the idea of the directors was also to speak about myself, as I am doing research about this long-lost artist and colleague, so to say. So the film has a lot layers, and its director Djordje Markovic was previously active mostly as an author of TV commercials. So it has a strong visual design, but is just as well deeply rooted in serious research. We were really discovering documents, right during the filming. I think that it looks really professional, but all is done the Serbian way, with very limited resources, and the smallest budget imaginable. Us cartoonists usually sit alone in the room and draw, but this was quite an adventure for me, the premiere in Belgrade was in a big venue with some 1500 (at least) people.

The film gathers historians, witnesses, and some comics connoisseurs and international stars like Robert Crumb, Mirko Ilic… As for plot keywords, the Internet Movie Database (IMDb) mentions: identity and violence…

ZOGRAF: We tried to film a number of comics-related people, artists and theoreticians, both from Serbia and abroad. We even had somebody all the way from Amsterdam, that is you, Zoran Djukanovic. But we also managed to find the older (!) sister of the cartoonist as well, in her 90s and almost completely senile, she wasn’t able to remember the names of her parents. But she used to compose music when she was young, and surprisingly – when she started to play piano in front of the camera, it was as if the 1930s were only yesterday…

This film took 7 years to complete, and during the filming Zdravko Zupan, comics historian and really good friend, died abruptly. It was he who actually started the researches about the fate of Veljko Kockar, a cartoonist active in pre-war Belgrade. We knew that he was shot in 1944 by the liberators of Belgrade, allegedly because he was collaborating with Nazis during the occupation. This sounded strange, because by knowing his comics (his main character was a kind of an introvert cactus-guy), it sounded unbelievable that he did anything which would even distantly be connected with any kind of propaganda. Our research only proved that he never collaborated with Nazis, and that most probably he was killed because of personal dislike or jealousy by someone who was probably well connected with the production of comics. Kockar was only 24 years old, and he didn’t even tried to escape Belgrade when the Nazis were withdrawing, while other cartoonists, who really collaborated with Nazis on creating the most disgusting propaganda, had left Belgrade together with the German army…

How do you perceive your friendship with Robert Crumb? When did it start and how it evolved through the years?

ZOGRAF: Crumb was one of the biggest inspirations for me to even start working on comics. I actually started a correspondence with Jay Lynch, another of the original underground cartoonist, while I was working in an animation studio in Belgrade, in the early ’90s. It was Jay who inspired me to start drawing comics more extensively, it’s a long story, and it was at the moment when I knew very little about alternative comics. But I knew about Crumb, and I knew that he is the greatest, the Picasso of comics, and by a strange twist of fate, I started to exchange letters with Crumb too at the moment when he was working on the final edition of Weirdo magazine, for which I did a 1-page comic. Anyway, this story was among the ones which were documented in a book named The Book of Weirdo written by Jon B. Cooke. During our early exchange of letters, I realized that Crumb knows a lot about early Serbian and Balkan music, and it was before it became fashionable, through Bregovic’s music and Kusturica’s films. Crumb learned about it through old recordings of the Serbian and other Balkans emigrants, which were made by American radio stations, way back in the 1920s and 1930s…

So we stayed in contacts for years, and he sent his drawings for the book that I co-edited for Kitchen Sink Press in 1998 I think, named Flock of Dreamers. It was an international anthology of dream-inspired comics. We also did a jam comic together, about me meeting Mr Natural on the streets of Belgrade. It was fun! When he came to Serbia for the first time in 2012, as a guest of Belgrade’s Comics Salon, I hosted a talk with him, in front of a tightly packed venue, with a lot of film directors, writers, and art people. Crumb is published and loved in Serbia, and during the Venice Biennale of Art, I designed the catalog of the Serbian pavilion, which included Crumb’s exclusive story – Serbia, the Land of Opportunity, haha. But basically, before I started to publish my comics, I was into exploring different dream states, and was known as a writer in my country, writing mostly about avant-garde rock music. I wrote about The Residents, during the early stage of their career, for example. And I never moved from my hometown, Pančevo, so contact with such luminaries as Robert Crumb was a deep and profound experience. When he agreed to appear in the film that we were making, it was a great encouragement.

You had once an opportunity to interview Will Eisner in the form of a comic strip?

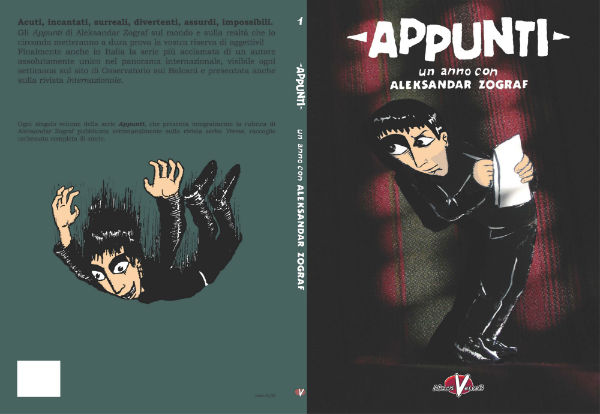

ZOGRAF: I met Will Eisner at the comics festival in Norway, it was shortly before he died, and he was constantly making fun of the fact that he was so old, and god only knows how long is he going to live. Anyway, I made an interview in between his talks, and decided to use it as a 2-page comic, rather than to write an article. We had a common friend, Andrea Plazzi, who was the editor of the Italian editions of my comics, and a European agent of the great Will Eisner. My opinion is that comics could also be used to create reports, or interviews, and that was just one of the many comics reports that I did.

You insist “It doesn’t matter where I live. I did not choose Pančevo (a smaller city neighboring Belgrade), I was born there, and it is a safe haven to which I return.” Are notions of the epicenter and the world periphery valid categories for you?

ZOGRAF: I think that world is round, so you can think of just any point in the map as a “center”, or perhaps “center of the universe, private or otherwise”. Pančevo is a great place to return, after an interesting trip.

Nevertheless, you travel a lot. Not only visiting comics festivals, but you also search for small, often neglected places, abroad as well in Serbia. What are you looking for?

ZOGRAF: I believe that world is incredible place, and very much worth exploring. Even some seemingly unimportant places could maybe hide a story within. I am often making comics about the little towns which don’t seem appealing – but I also did a story about Venice, the most visited place by the tourists from all over the world, as seen by its inhabitants, often sarcastic and humorous, since it’s hard to live in a town with canals instead of streets. They know that it appears beautiful, and it is, but yet it is also difficult…

Along the years, your creative interest was slowly shifting from “hypnagogic visions” (the haunting imagery that occurs in a state between sleeping and waking) towards subjective archeology of small, neglected and forgotten fragments of everyday life from the past…

ZOGRAF: Past some years, I am really obsessed with archaeology. Especially from the prehistoric times – Balkans is a rich soil for the exploration of that kind of artifacts. I learned to pay attention to the details around me, and if you know what you are really looking for, you may find objects (or, more often, fragments of objects) made by people 1000s of years ago. We are stepping on it! These objects are telling stories, we just have to learn to be sensitive to it.

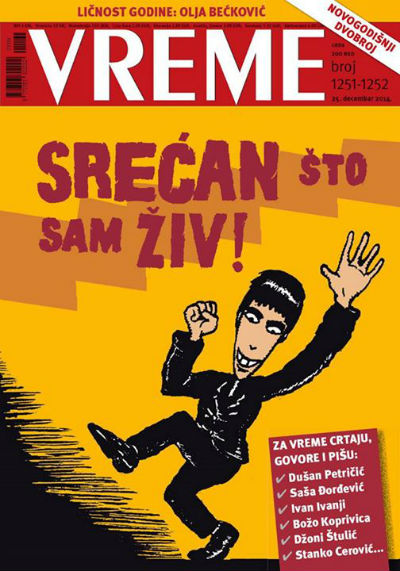

How important was your decision to start regular work at Vreme, an independent political weekly in Belgrade, at the approximate rate of two pages in color per week? Did that lead you to focus on short autobiographical records, travelogues and history?

ZOGRAF: Yes, since I started to publish with them in 2003, now the overall number of pages published exceeds 1000 pages! And it’s always a different story each week, so it demands research and self-discipline to find the new material. Sometimes I would do a travelogue from some trip, sometimes it’s an illustration of a passage from a forgotten book from the 1930s, or a letter found in a flea market. So I learned to track down all these things. It was a process which made me learn a lot about people, about history, about myself. Also, the very existence of an ever approaching deadline is a great thing to keep you productive…

Can you explain your utter fascination with flea markets? You are finding things there by chance. Or, is there a method in it? How it became a poetic device in your hands?

ZOGRAF: Flea markets are great, because you never know what you may find. It’s utterly different from going to a regular shop, for example a shoe shop. You know the size of your shoes, and you pick up one pair among the 5 or 6 models or something. But in a flea market, it could be anything coming your way. This feeling of numerous possibilities feeds my curiosity, and it quietens my intellect which is always caring about practical problems. Somehow it all makes me dive directly in the subconcious, maybe collective subconcious – there hardly is a method to it, but I find some sort of poetry in searching and finding stories behind things.

How do you handle the political dimension of life in Serbia? Populism entered Serbia much earlier, almost three decades before it invaded politics globally?

ZOGRAF: I work for the independent political weekly, and I occasionally enjoy meeting journalists, because they know a lot of things going on behind what you read in the news. But it’s most of the time hard to predict political developments; at least it’s difficult for me. I never expected that Yugoslavia would split in a bloody war. In Serbia we went through all kind of political instability, so we learned how to cope with just any kind of crisis. I believe that populism is a signal of crisis – the fact that it’s present all over the West now means that Western societies are in a kind of crisis. Despite all the resources, and the technology, modern people live stressful, difficult lives, but going through crisis also could be a part of the learning process. So, as contradictory as it may sound, idiotic populist politicians could actually teach us how to find the balance within and overcome the hardships imposed by the society – it’s a painful process, which may take years…

You are a short form master. Have you ever considered creating a graphic novel?

ZOGRAF: I don’t know, maybe it will happen someday, but I enjoy creating shorter stories. It is something that is not selling well in today’s market I know but it enables me to explore more details, more subjects. I often find graphic novels too ambitious, too baroque, while I prefer exploring little things. At the market, I always buy smaller tomatoes, and I find them more tasty then the big ones.

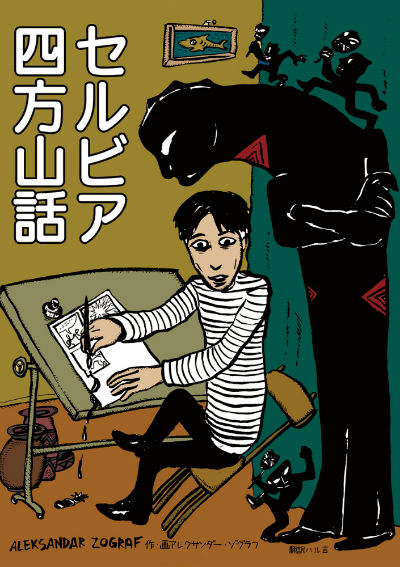

In Japan, the second book of your comics has been recently released… In how many countries you have been published in up to now?

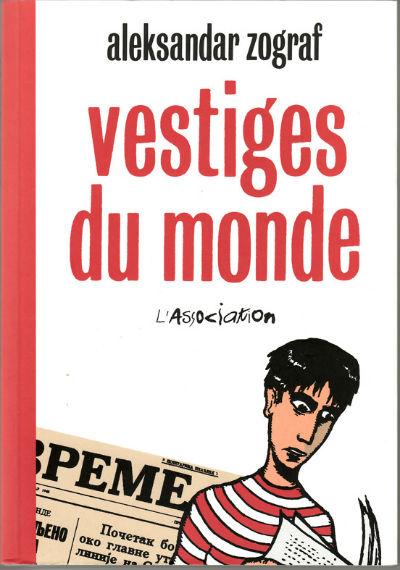

ZOGRAF: One of the things that I enjoy, is getting in contact with people from many different countries, many different realities. My solo books came out thus far in the US, the UK, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Japan, Croatia and Serbia, if I remember correctly. But I published in magazines in many more countries. It’s great how art could overcome the boundaries these days – you don’t have to be stuck in your little club, in your little country, in your little village. The modern world puts you in contact with somebody 10,000 km away, in a minute, and you may not even have to leave your little village while making these contacts. Don’t you think it’s fun?! Should we use it somehow? Yeees!

You are preparing a new World War II comic book collection for an Austrian publisher…?

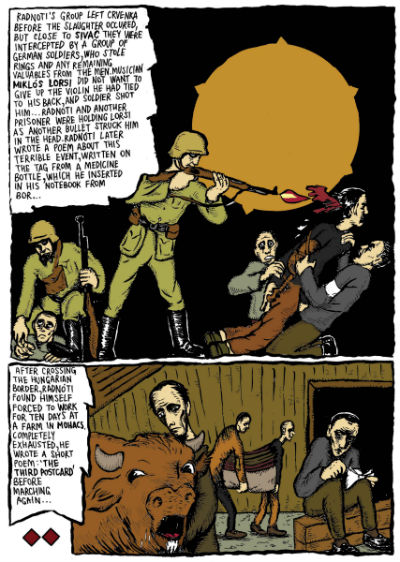

ZOGRAF: Yes, during the years I have accumulated a number of stories from the Second World War. These were special times, the whole of humanity went into a trance-like state, while confronting the violence on such a large scale. One of the stories is about the Jewish-Hungarian poet, Miklos Radnoti, who was among the people sent to the labor camps in Serbia, established by the Nazi occupiers. There are large copper mines in Eastern Serbia, and Germans needed it for their war industry. So this little town and its surroundings was transformed into a conglomeration of 40 labor camps, where people from all over Europe, mostly war prisoners, Jews, and Slavs, would toil like slaves. Radnoti wrote the poetry while in the camps, and during the forced march when he was eventually was killed by the guards, just in front of the Hungarian-Austrian border. His poetry was found in the mass grave a few years later, and somehow his poetic substance managed to survive even though his biological existence had to end. After he died, he became one of the most respected poetical figures in the post-war Hungary, and all over the world. This is just one of the stories that will be enclosed in this book…

Your wife Gordana Basta creates impressive embroideries based upon panels from your comics and from some other comic artists. I know about seventy of them. Did she contemplate to collect them for an exhibition?

ZOGRAF: Gordana was making embroideries for years. It’s funny because it is work that cannot be done in a fast way. It requires time, and patience. Even though it’s rather modern in expression, the technique is quite an old one, and is now part of the traditional art in this part of the world. It’s interesting to know that ethnologists think that embroidery (as part of the kitchen ornamentation) actually reached the Balkans through Central Europe, but it originates from Holland.

Yes, Gordana has made quite a few exhibitions, mostly as part of the Aleksandar Zograf’s expos, in many European countries. And she is preparing to exhibit jam drawings embroideries, with participation of cartoonists from several countries, but it’s still in progress. As I said, it takes time.

When in mid-July the president of France Emmanuel Macron visited Serbia, he met you. Enki Bilal was with him. What was the purpose of that meeting?

It’s a rather bizarre development, and a long story, but generally I was invited by the French Institute in Belgrade to coordinate the exchange of Artist in Residence programs among the town of Angoulême and my native Pančevo. It means that selected Serbian cartoonists will stay in Angoulême for some time while the French will come to Pančevo. It became part of the inter-state agreement, and Enki Bilal, who was born in Belgrade but is one of the most important figures of French comics and film, has worked on making it possible. During his visit to Belgrade, French president Macron insisted on talking with the local artists, so that is how I met him and explained this idea etc. I think that the whole project is very positive, because it brings different realities together, and enables a great exchange of ideas.

For more on the work of Aleksandar Zograf visit his site here

Interview by Zoran Djukanovic