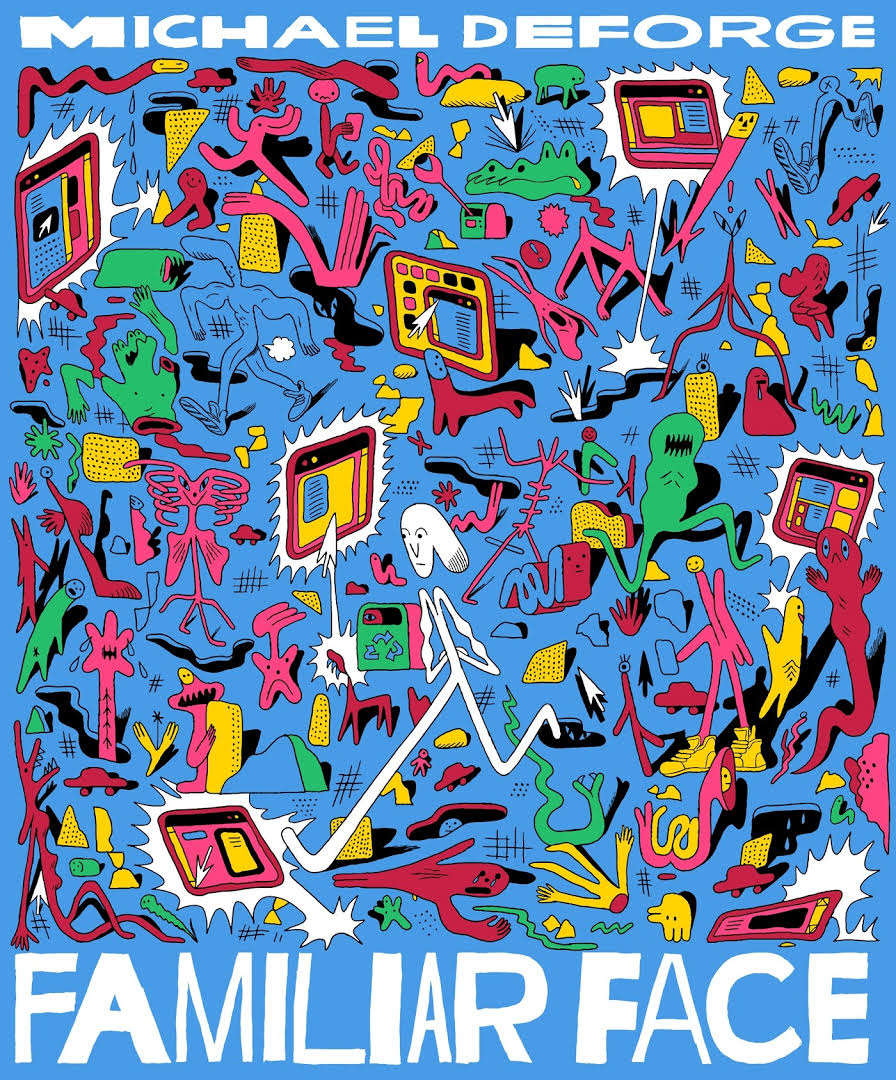

For all the surface appeal of Michael DeForge’s frenetic pop surrealism, his real gift is an ability to use that dazzle to land punches of sobering pathos and wry commentary on the particular flavour of the modern world.

In his latest full-length book, Familiar Face, he takes a very timely look at the effect on us of the technology (and the companies that produce it) that we eagerly embrace every time we grab a sparkly new tool and click the little box to say we accept the terms and conditions.

In his latest full-length book, Familiar Face, he takes a very timely look at the effect on us of the technology (and the companies that produce it) that we eagerly embrace every time we grab a sparkly new tool and click the little box to say we accept the terms and conditions.

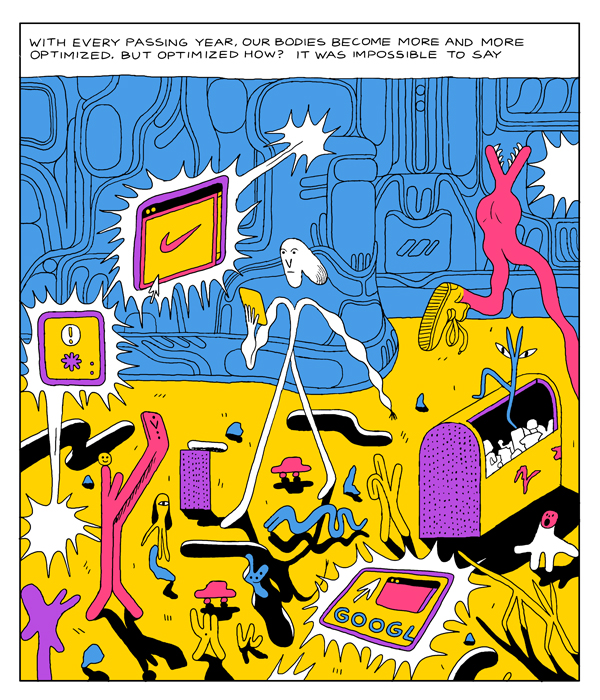

DeForge plunges us into a world where it’s not just the apps on our phone that keep constantly updating. Instead, the very fabric of the world is subject to an “unending stream of fixes, upgrades, refinements, additions and subtractions”: roads disappear or turn into inescapable cul-de-sacs; doors suddenly lead to new places; even body parts are added, removed or amended, leaving the book’s protagonist unable to recognise herself in old photographs.

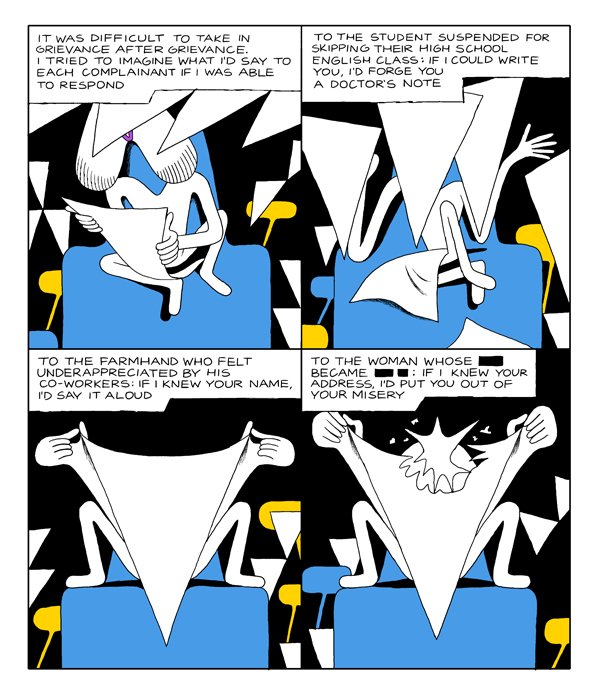

That protagonist – never named – works for the government department that deals with complaints. However, her only task is to read them, in an apparent effort to give the process a human element. The complaints themselves – a mixed self-regarding bag of whingeing grievance, emotional trauma and paranoid fantasy that will be familiar to any Twitter user – are dealt with elsewhere by another automated system, and she has no idea how or even if they were resolved.

The nature of her work intensifies her alienation: “Some days it was difficult to not come home with the impression that the world was populated with whiny crybabies”. However, the situation at home doesn’t offer any relief. She and her girlfriend are not allowed to know each other’s jobs (as a “safety precaution”), although the protagonist senses that her partner is one of the city’s meddling cartographers.

The nature of her work intensifies her alienation: “Some days it was difficult to not come home with the impression that the world was populated with whiny crybabies”. However, the situation at home doesn’t offer any relief. She and her girlfriend are not allowed to know each other’s jobs (as a “safety precaution”), although the protagonist senses that her partner is one of the city’s meddling cartographers.

Things come to a head when, during an overnight upgrade, the girlfriend vanishes. Or has she left of her own volition? After some fruitless attempts to track her down, the protagonist becomes convinced that her ex is part of a resistance movement – a group of rogue cartographers that hacks the automated map system to make their own radical changes to the city. As the updates become more erratic, she begins to sense that they’re messages from her ex. Desperate to rekindle their relationship, she begins to look into finding and joining the cell.

Running through the book’s various threads and diversions is a very familiar sense of unease about the amount of agency we hand over when we sign up to apps and providers that barge their way digitally into our lives. One of the book’s most telling sequences features an online bank enforcing its ID protocols with the outbursts of a controlling and neurotically overprotective parent. As we eagerly check our social media for likes and shares, to what extent are we letting our feelings be programmed by the environment we’ve backed ourselves into?

Running through the book’s various threads and diversions is a very familiar sense of unease about the amount of agency we hand over when we sign up to apps and providers that barge their way digitally into our lives. One of the book’s most telling sequences features an online bank enforcing its ID protocols with the outbursts of a controlling and neurotically overprotective parent. As we eagerly check our social media for likes and shares, to what extent are we letting our feelings be programmed by the environment we’ve backed ourselves into?

That intrusion is characterised by the protagonist’s increasingly impertinent personal digital assistant. At one stage it bursts out of character, telling the protagonist, “It’s OK to be mad… Hold onto it! It’s what makes us human” (my emphasis). Later, the PDA becomes one of the protagonist’s complainants, revealing that its design is meant to “simulate the tangle of disgust, co-dependence and infatuation of ‘natural’ relationships”.

DeForge’s familiar graphic style depicts vividly the feeling of being overwhelmed by a visual torrent of icons and logos competing for your focus. Meanwhile, the surreal physicality of his characters highlights the constant change they face. Overall, the book captures the exhausting digital lust for superficial novelty – an ever-accelerating race in which The New Thing is always The Best Thing and no-one dares to comment on the emperor’s new clothes. The book might end in a slight anticlimax (albeit with the teasing hint of a ‘happy’ ending), but throughout its 170 pages DeForge evokes a palpable sense of the impermanence and insecurity that increasingly characterise the contemporary capitalist world.

Michael DeForge (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly, $21.95

Review by Tom Murphy