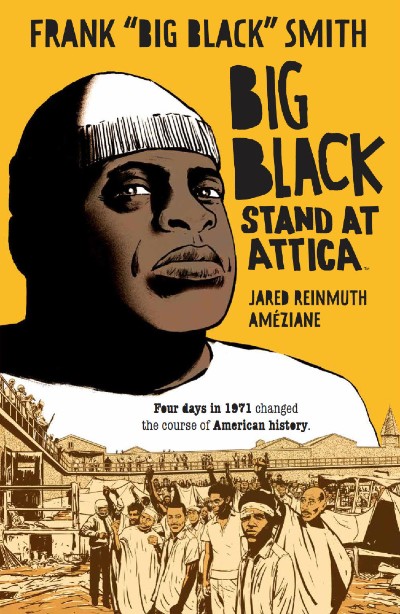

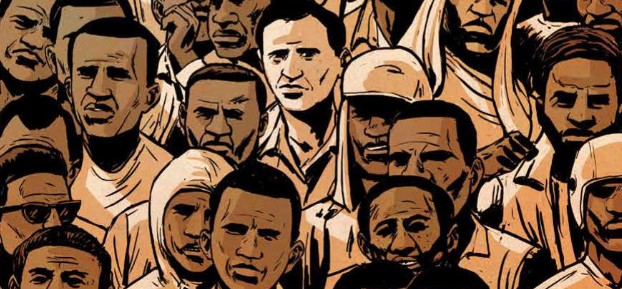

Recalling a moment in US history from 1971, the story of Frank ‘Big Black’ Smith and the Attica State Prison rebellion feels no less timely today. A collaboration between Big Black and Jared Reinmuth (whose attorney stepfather Dan Meyers filed the Attica Brothers’ civil suit in 1974), the graphic novel recounts how a peaceful rebellion of unarmed inmates was met by bullets and tear gas at the hands of New York State troopers, Deputies, and Corrections Officers. A face-off divided along racial lines, with one side requesting such basic human rights as nutritious meals, freedom of religion and access to medical treatment; and the other seeking to aggressively demonstrate their dominance; the traumatic events at Attica and ensuing government cover-up remain resonant as ever, and must be known.

One shower per week. One roll of toilet paper and one bar of soap per month. These were just some of the inhumane living conditions which inmates at the Attica maximum security penitentiary endured. Titular character and narrator Big Black – a figure respected by guards and inmates alike, and who plays an integral part in this story – earned just 30 cents a day in his job at the prison laundromat; measly pay for what essentially amounted to slave labour. Designed to deny the predominantly Black prison population of their dignity as human beings, the systems and circumstances at Attica and similar institutions around the United States in many ways represented a ‘new plantation’ for the incarcerated. Upon their release, inmates would be set forth into the world with just forty dollars and a suit to their name; a package reminiscent in both cadence and concept to the ‘forty acres and a mule’ promised to freed people after the fall of the Confederacy.

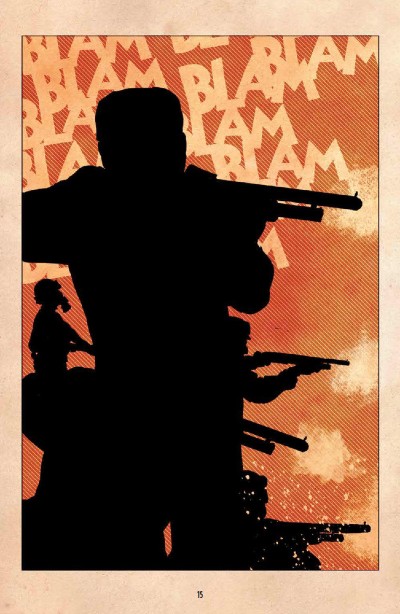

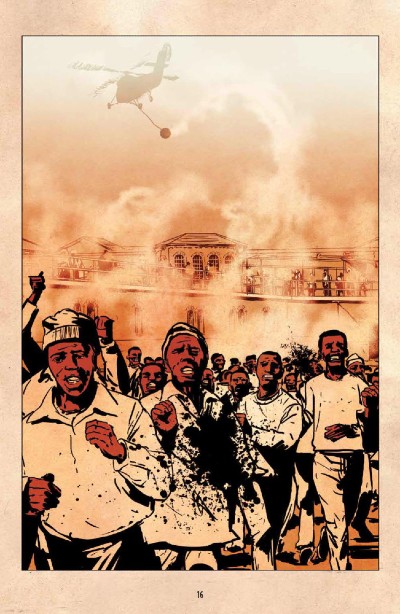

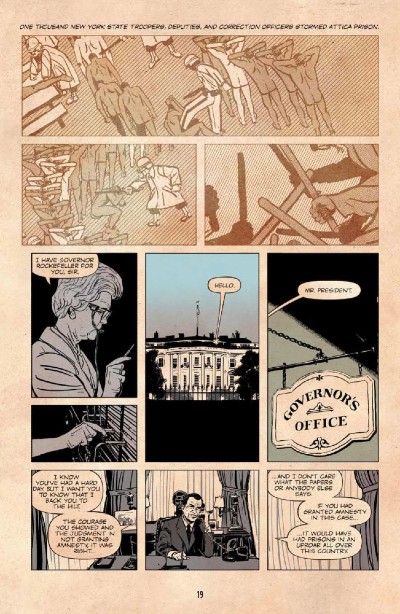

A strike in the metal shop, silent fasting, and a manifesto drafted for the attention of Prison Commissioner Russell Oswald were some of the non-violent means by which inmates at Attica hoped to rectify the abuses inflicted on them when tensions reached a head in September 1971. But when a guard was injured trying to break up a misinterpreted sparring match between two prisoners, the powder keg of an already fraught atmosphere was ignited, and the Attica Prison riot was begun. We see how his fellow inmates – who would become known as the Attica Brothers – appointed Big Black to act as their chief of security, making sure both inmates and negotiators were safe during the rebellion. However this preservation of human life was not a priority for their adversaries. Peaceful negotiation was not of interest to Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who ordered 1,000 state troopers to storm the prison, resulting in the deaths of 29 inmates, and 10 of the correctional officers and civilian workers they had taken as hostages. More than 80 others were injured.

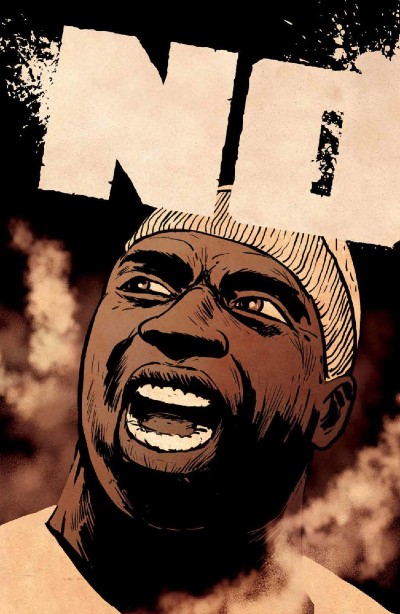

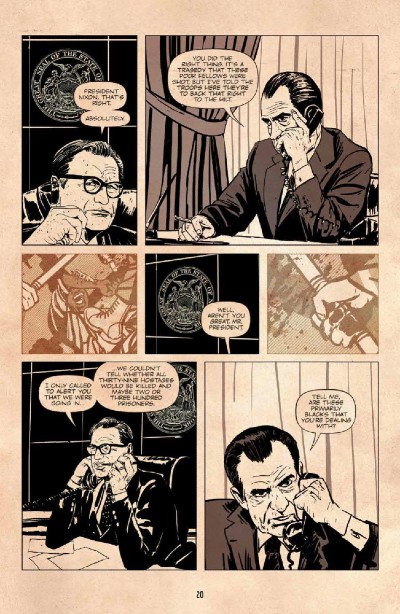

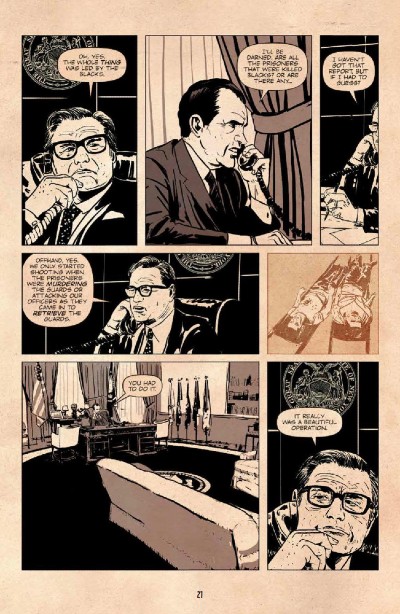

Stand at Attica opens with a graphic depiction of these defenceless men being gunned down by faceless shooters in riot gear, before contrasting the chaos of the prison yard with the clinical calm of the Governor’s office, as Rockefeller – himself known to harbour presidential ambitions – informs President Richard Nixon over the phone that the prisoners shot were “primarily blacks”, and that the violent retribution exacted on these unarmed men “really was a beautiful operation”. Such juxtaposing vignettes are where artist Améziane (Cash Cowboys, Clan) transforms an otherwise scholastic-style text into graphic storytelling. Chapter title pages adopt a blaxploitation aesthetic à la Luke Cage (incidentally the bulletproof character first appeared in Marvel’s pages one year after the events at Attica), and panels are shaded in a sepia toned, film grain style; subliminally reminding the reader that this is not fiction, but instead a chapter of history. One particular wordless sequence seemingly pays homage to the graphic style of Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party.

Elsewhere Améziane employs a recurring visual motif of Big Black in the posture of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man; a figure of humanity, strength, and beauty, which in many ways represents all that the prison guards tried to strip from the Brothers, through hideous torture methods intended to emasculate and demean. Central antagonist Officer Holt is characterised by demonic eyes bulging from snarling face that just about foams at the mouth. Holt and his men are shown to have snuffed out those kind white voices which did exist on the prison staff, highlighting how white men are also the victims of toxic white masculinity. Meanwhile the inmates treated their own hostages with dignity: “They was beastly to us, but we was humane to them”, one of the Brothers is quoted.

The depiction of the media and its impact on public sentiment is another of Stand at Attica‘s strong points, and one which makes the events of 1971 feel chillingly reflective of today’s reality. The reader learns how news reportage on the rebellion neglected to mention what exactly the prisoners were demanding in their demonstrations, instead alluding to the prisoners’ actions as part of an “international conspiracy”. Government officials broadcasted barefaced lies intended to paint the inmates at Attica as savage and inhuman, thereby collectively framing them for the State’s own crimes. Primary among these untruths were the claims that the Attica Brothers had murdered their hostages — a statement later proved false as autopsies showed the deaths were caused by trooper fire — and that officers had fired at the prisoners in self-defence — when evidence proved that the prisoners were shot in the back, or back of the head. Those recognising the cover-up for what it was are shown demonstrating their solidarity in the streets, carrying signs with such slogans as “no justice, no peace”. These images feel especially current. Big Black and co-writer Jared Reinmuth credit the support from this protest movement and such Black leaders as Angela Davis, alongside the facts revealed by Medical Examiner John Edland’s autopsies of the hostages, for amplifying the positive impact the prisoners’ rebellion would eventually have on American society. However the trauma that would remain long past the events at Attica, and the fact that these abuses continue to underlie our society today, question whether ‘justice’ can ever be truly achieved.

While Big Black: Stand at Attica‘s educational tone might recommend it for a classroom setting, its writers quite rightly refuse to shy away from depicting the relentless violence, both physical and psychological, committed against the inmates. Nor do they tone down the hateful racist language spouted by those in Government, the media, and the general public. This decision to include more mature content makes the graphic novel feel more authentic and relevant, yet may prevent it from reaching a younger, school-aged audience which might otherwise benefit from its timely message. A remaining question pertains to the nature of the collaboration between Reinmuth and Big Black (said to have existed since 1997), considering Big Black’s death in 2004 and the graphic novel’s 2020 release. Greater transparency here would be a valuable, though not necessarily deciding, addition to the work.

For an in-depth account of the Attica State Prison rebellion, Heather Ann Thompson’s Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy is considered a definitive text on the subject.

Frank ‘Big Black’ Smith & Jared Reinmuth (W), Améziane (A), Andworld Design (L) • Archaia/BOOM! Studios, $19.99/£14.99

Review by Ally Russell Shields