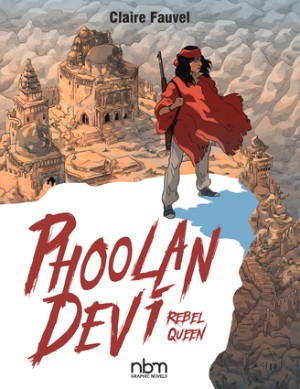

What could compel Claire Fauvel, a French illustrator and animator, to create a 220-page graphic biography of Phoolan Devi, arguably India’s most famous dacoit? A question like this would never have been asked of filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, of course, who made a film on Devi called Bandit Queen in 1994 and was sued by his subject who disputed its accuracy. And yet, the implication that a perceived outsider cannot comment on culture is absurd.

What could compel Claire Fauvel, a French illustrator and animator, to create a 220-page graphic biography of Phoolan Devi, arguably India’s most famous dacoit? A question like this would never have been asked of filmmaker Shekhar Kapur, of course, who made a film on Devi called Bandit Queen in 1994 and was sued by his subject who disputed its accuracy. And yet, the implication that a perceived outsider cannot comment on culture is absurd.

Fauvel’s answer to the question lies in her foreword, which explains how she stumbled upon the dacoit via stories written by her father. She was captivated instantly, which has often happened to most people even vaguely familiar with the strange, difficult, and compelling life of Phoolan Devi.

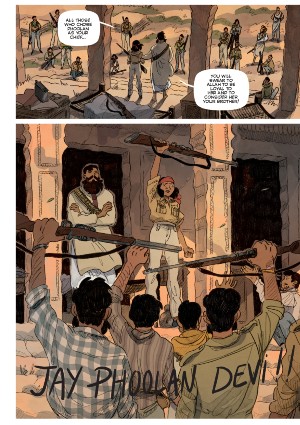

Born into an impoverished family in rural India, married off as a child, pummelled by an unforgiving caste system and tyrannical patriarchy, Devi could easily have succumbed to her fate like millions of other Indian women in her position but chose to fight instead. She broke free of a society that had consistently let her down, embraced the life of a dacoit that she had no choice but to accept, and eventually returned to become a member of Parliament. It makes for the kind of story that would inspire anyone, working in any medium, irrespective of language.

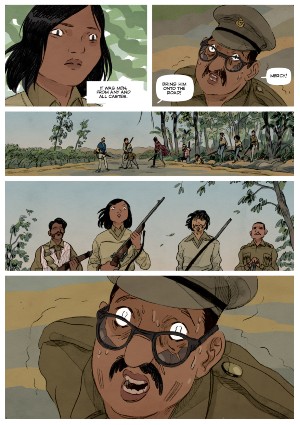

Fauvel’s book first appeared in French in 2018, and this new English translation by Montana Kane suffers in parts, especially with spelling errors that could easily have been avoided. That seems like a minor quibble though, when one acknowledges the obvious homework put in by Fauvel to get nuances about her heroine right. There are the signposts in Devanagari script, for instance, the right use of titles for relatives and, most impressively, the accurate depiction of posture and clothing that could only have been possible if Fauvel visited the places she recreates in her pages.

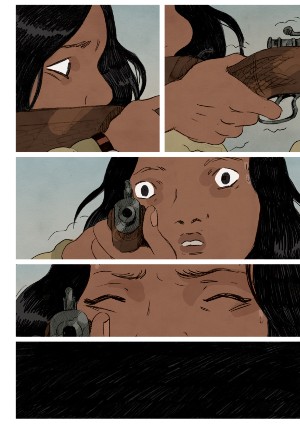

There are many horrifying aspects of Devi’s story that are hard to stomach, such as her marriage to a man who was decades older, her assaults at the hands of her husband and then the police, and other instances of casual violence that are accepted as a matter of course by India’s lower castes. To Fauvel’s credit, she deals with these incidents in an understated manner. A simple panel depicting Devi’s tiny hand in the grasp of a man’s large fist, for example, cuts to the heart of how unnatural the act of child marriage is.

Phoolan Devi was not an innocent woman. Her years as a dacoit resulted in crimes ranging from robbery to kidnapping and murder. She spent over a decade in prison before her controversial release and her rehabilitation, but her past caught up with her in 2001 when she was assassinated.

Fauvel chooses to end her story at the moment Devi steps out of prison, not knowing where life will lead her next. It is a poignant way to finish, especially for those who know how the story ends.

Review by Lindsay Pereira