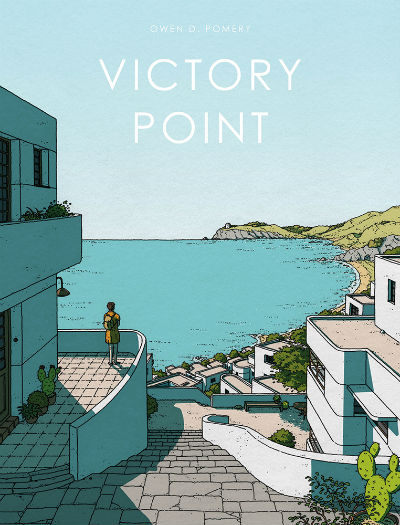

Owen D. Pomery’s Victory Point tells the story of Ellen, a young woman who returns to the seaside town she grew up in – the titular town – and brings with her a new perspective gained through her years in the city. Pomery is a constant creative; this is already his second graphic novel to be released this year. As with all of his work, this is a comic that really deserves commitment; every panel invites exploration and, in return, offers a breath of fresh sea air. As the reader wanders through the streets with Ellen, this invitation extends further as antithetical considerations of permanence and change are woven throughout.

Owen D. Pomery’s Victory Point tells the story of Ellen, a young woman who returns to the seaside town she grew up in – the titular town – and brings with her a new perspective gained through her years in the city. Pomery is a constant creative; this is already his second graphic novel to be released this year. As with all of his work, this is a comic that really deserves commitment; every panel invites exploration and, in return, offers a breath of fresh sea air. As the reader wanders through the streets with Ellen, this invitation extends further as antithetical considerations of permanence and change are woven throughout.

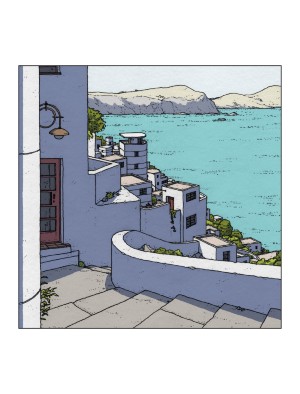

On the one hand, Victory Point encapsulates that feeling of returning to a smaller town after moving to the city, the contrast of the fast-paced city-life to the life left behind making the latter appear stagnant and consistent. Indeed, Victory Point is a decisively unchanging town, due to its nature as an archaeological experiment. Yet, on the other hand, Pomery draws attention to importance of perspective. Ellen may return to her dad in the same home she has known since a child, the same shops in the same places they were before, the same garage run by the same family, but there is also the flipside of this apparent precedent for perseverance: the change within the details. For example, the shop owner Gemma has moved up the ‘corporate ladder’ since Ellen has been away and has had children, Ellen’s dad has been making progress building his boat, and a new café has appeared.

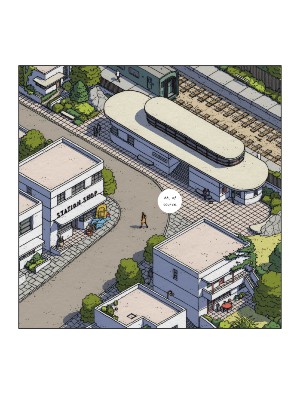

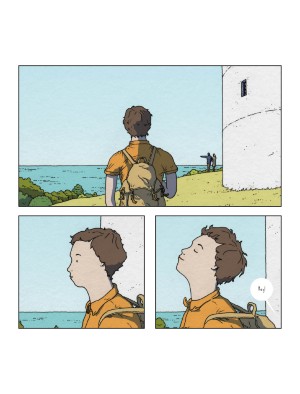

It is this attention to detail that is encouraged also in the artwork itself. The linework is intentional down to the minutiae of every shrub and every shape of dappled sunlight. As Ellen walks through the streets of Victory Point, the details in the landscape converge so that we can smell the salty sea in the air and feel the warmth on our skin. The heat is palpable in the selective use of high contrast shadows. Certainly, without the use of gradients, Pomery’s technique allows this notion of perseverance to pervade every panel. It is the landscape that endures, with its intricacies and deliberation. Conversely, characters are illustrated with a refreshing simplicity. As is discussed in comic theory, the more devoid of realism a character is, the more this allows for self-projection. For Pomery, this simplicity is utilised especially in the facial features of characters; whereas clothing is personal and individualised, faces are made up of a few simple lines. Ellen becomes a convenient channel for the reader’s keen eyes, allowing us to take in the details of Victory Point along with her.

These details are further fleshed out for the reader through the spaced interruptions of Pomery’s text-based paragraphs. Again, this continues to add weight to the notion that perspective is built up through various layers of details, with these layers corresponding to varying layers of perspectives and beliefs. The narrative itself, by revealing only fragments at a time and focussing on the visuals within the panels, routinely asks the reader to piece things together as they go, only to inform them directly at a later point.

By forcing the reader to seek out meaning in the details, Pomery encourages a concurrent acknowledgement of the act of comic-creation itself. Starting the comic with the train arriving at the station tells the reader clearly that a journey is taking place and, therefore, that an unbridled attention is called upon. Each panel is shouting to be given its due quota of focus and admiration. It is only then that Victory Point will reveal itself as something that is really as fluid and nebulous as the rest of the world, and just as susceptible to change as anything else. As one character admits candidly when talking to Ellen: ‘I don’t think it suits me to see anything as too permanent”.

Owen D. Pomery (W/A) • Avery Hill Publishing, £14.99

Review by Rebecca Burke

[…] • Rebecca Burke reviews the refreshing antithesis of Owen D. Pomery’s Victory Point. […]