One of the many problems facing aging freelance writer Max Winter is that his pulp-magazine publisher has taken the rights to his cowboy character, the Red Rover Kid, away from him. Pulp’s creative team, Ed Brubaker and the father-and-son Phillips, also tackled creator rights in their Criminal trade-collection Bad Weekend. But while Hal Crane was embittered his successful cartoon-strip provided little reward, Max’s cost is more personal. See, these pulpy Westerns are autobiographical, based off Max’s own experiences as an outlaw during the last gasp of the 19th century in the Wild West. Now scraping by in 1930s Depression-era New York, Max’s life-story is falling out of his hands like his heart is weakening with age. Max wants to tie things up, to let his Red Rover Kid move onto new adventures. But the publishers wish to keep him in the familiar routine, ironically pushing Max back into his former outlaw ways to make ends meet.

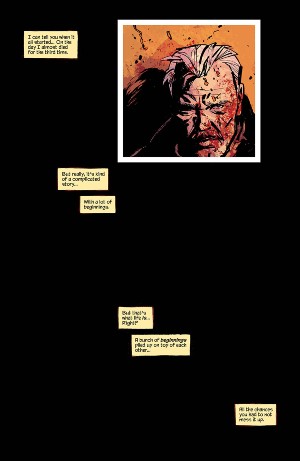

Brubaker often writes world-weary people making desperate, if calculated, bids to secure themselves. He crafts characters who feel authentic and lived-in, Max demonstrating his knowledge of both bank robberies and freelance writing without it feeling expository. Brubaker writes Max’s internal narration with that wonderful mix of sympathy and understatement, allowing him to become a relatable protagonist without being irreproachable. Max remembers fleeing some cattle-barons in Wyoming, when his brother was shot in the spine, and Max didn’t even turn around. It’s these details which enrich Max’s character, who views these flashbacks with regret, and also a certain wistfulness.

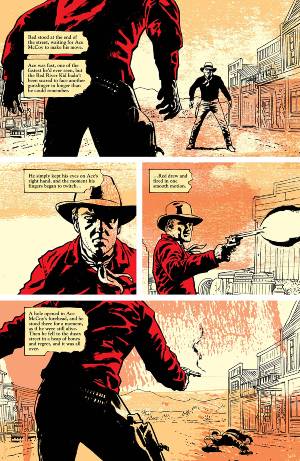

The flashbacks are especially vibrant thanks to Jacob Phillips’ colouring. He renders the 1899 West in sun-drenched gradients of orange and yellow, the bright-red coat of the Red ‘Rock’ Kid (Max making minor efforts to alter details) standing out. These colours fill the whole panel, becoming a background for the sharp line-work of Sean Phillips (Jacob’s father) who pencils and inks Pulp. Their artwork is dourer and heavier during the 1930s, capturing its gritty urban environment. Phillips reliably brings vivid detail to the backgrounds, and the gestures and expressions of the characters.

Pulp also sees Max encounter the 20th century threat of Nazism, which has prominent support in pre-WW2 New York. Pulp doesn’t exactly interrogate this American Nazism, aside from showing its existence, but it does provide a cornerstone in Max’s disillusionment with a cruel world, and a point to measure his potential ‘redemption’ against. However, more than most Brubaker works, Pulp is rather tied to Max’s perspective. It lacks the ensemble casts of Gotham Central or Criminal, nor are ‘pulp-magazines’ explored with the same depth as the ‘comics industry’ was in Bad Weekend. Max is a fine character, but the tight focus of Pulp only expedites a very brisk and economical read.

Pulp, for better or worse, is pretty much what you’d expect from Brubaker and the Phillips. Max mentions wanting to free his characters from genre conventions, but although Pulp itself does have a retirement-age protagonist, his story is a familiar one of crime and tragedy. The time-setting and pulp industry are ultimately minor set-dressing over typical themes. But Pulp is undeniably well-made even if it’s recognisable, showing you don’t have to reinvent the wheel to deliver a good story. Brubaker and the Phillips remain a fantastic team for satisfying and compelling crime stories. They might have remained in their comfort zone, but for the moment, they show little reason to move out.

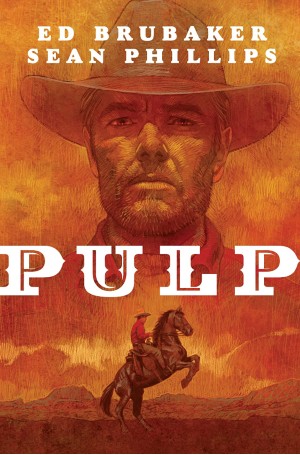

Ed Brubaker (W), Sean Phillips (A/L), Jacob Phillips (C) • Image Comics, $16.99

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong