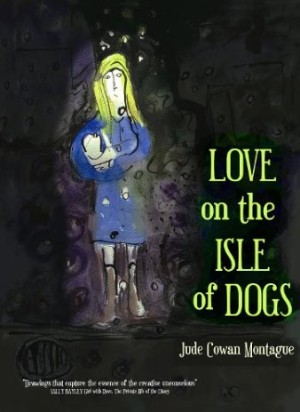

On the surface, Love on the Isle of Dogs is a story about love that constantly interrogates itself, asking even in the beginning: “What & Who is Love anyway?”. This interrogation is reflected in the act of recollection itself, as Montague reflects upon her relationship with a man suffering with extreme paranoia, among other mental health issues, following from a head trauma. On this deeper level, Love on the Isle of Dogs is about truth as much as it is about love, and maybe even more so. It is about hard truths, subjective truths, and the colliding truths of two souls trying to form an unbreakable union together, using love to stitch the pieces together.

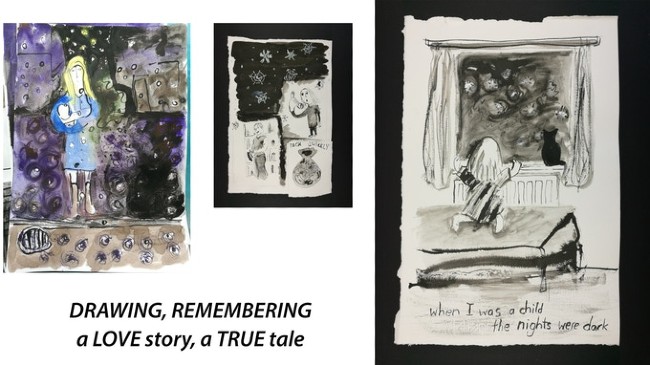

Love on the Isle of Dogs continuously engages with its own narrative whilst also observing it from a distance. For example, Montague often draws herself standing beside herself, both as a natural consequence of the unpanelled illustrations being boundless and free-floating, and as a visual representation of this engagement with the self. The truth is being bargained with and reconciled as Montague constantly questions what to show, what to leave out, what was real and what was perceived. On some pages, the emotions are the only truth left for the reader to grasp as the chronology is left patchy and inconclusive. Yet, we always feel around the edges of what is being depicted – feeling it resonate through the emotions on the page. We know, but we also do not know. This appears to be one of the aims of the comic itself: for Montague to filter through her own past and to reconstruct the narrative within.

Love on the Isle of Dogs continuously engages with its own narrative whilst also observing it from a distance. For example, Montague often draws herself standing beside herself, both as a natural consequence of the unpanelled illustrations being boundless and free-floating, and as a visual representation of this engagement with the self. The truth is being bargained with and reconciled as Montague constantly questions what to show, what to leave out, what was real and what was perceived. On some pages, the emotions are the only truth left for the reader to grasp as the chronology is left patchy and inconclusive. Yet, we always feel around the edges of what is being depicted – feeling it resonate through the emotions on the page. We know, but we also do not know. This appears to be one of the aims of the comic itself: for Montague to filter through her own past and to reconstruct the narrative within.

This calls to mind the writing of the Existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre who, in his prose work Nausea, discussed the human inclination to force a narrative lens onto our experiences: “This is what fools people: a man is always a teller of tales, he sees everything that happens to him through them; and he tries to live his own life as if he were telling a story”. Comics are, of course, one such medium that allow us to structure our experiences sequentially. Yet, Love on the Isle of Dogs holds itself accountable to this notion of an imposed narrative. First, we are given the illustrated version of events, and then the written account. This comparison allows the reader to consider the functionality of the comic form whilst testifying to comics’ versatility and ability to do things that prose narrative alone cannot. In fact, you feel obliged to reread the comic after the insights revealed in the prose: to put more pieces of Montague’s world together.

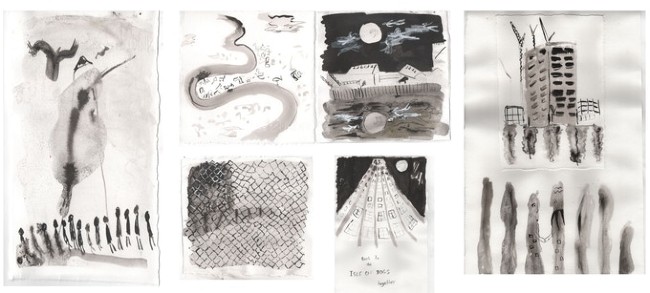

The temperamental nature of memory is a major theme of the comic, shown through landscapes that are abstract and incomplete, featuring broken bridges, floating roofs, and dissolving skyscrapers. The disproportions of these illustrations lend themselves to the varying weights of one moment compared to the next, and the chaos of these recollections: sometimes the husband is reduced to disembodied facial features, showing us where the focus has shifted and where priorities now lie. Often it even appears as though fragments of paper are layered on top of previous iterations of the layout so that the pages themselves become a physical manifestation of the knitted quilt of memories Montague is sorting through.

Plus, the choice of ink as the exclusive medium in Love on the Isle of Dogs also affirms this act of recollection: the high contrast of the black against the white page marks out the clear binary between that which is forgotten and remembered. Additionally, where strokes are less precise, this brings with it a sense of uncertainty or overpowering emotion. As Montague’s husband will remark to a doctor later on: “black and white are honesty”. This reveals Montague’s ongoing commitment to the truth whilst also epitomising the difficulty of this task due to the distorted reality of her husband’s mental illness.

As well as an act of intense self-reflection and recollection, Love on the Isle of Dogs is a vulnerable story about the exasperation and devastation of loving someone who is suffering internally to themselves, and the isolation and self-deception this can result in. It reveals how one person’s trauma can seep into others. It is this shared trauma that leaves Montague shouting at buildings: “What is happening”, until they bend and recoil from her words. There is desperation in the scrawled handwriting – “who can I talk to?” – as ink blots the paper like inky tears: “There was something on his mind. If only I knew what it was!”.

Love on the Isle of Dogs asks us to question the nature of truth and consider whether something is true just because we believe it. For her husband, his distorted reality was completely true and real to him, for Montague as a child, catching a falling star was as true as anything else could be, as she insists to us: ‘it’s what really happened’, and for the reader, well, they will finish reading with their own unique version of the truth. By telling this story in such an abstract and experimental way, Montague is asking us to question what truths we can discover through comics, and whether it really matters if the truths we take away are an actual representation of the way things unfolded, or whether the most important thing is the impact these truths have on us.

Jude Cowan Montague (W/A) • Friends of Alice Publishing, £10.00

Review by Rebecca Burke

[…] • Rebecca Burke reviews the versatile experimentation of Jude Cowan Montague’s Love on the Isle of Dogs. […]