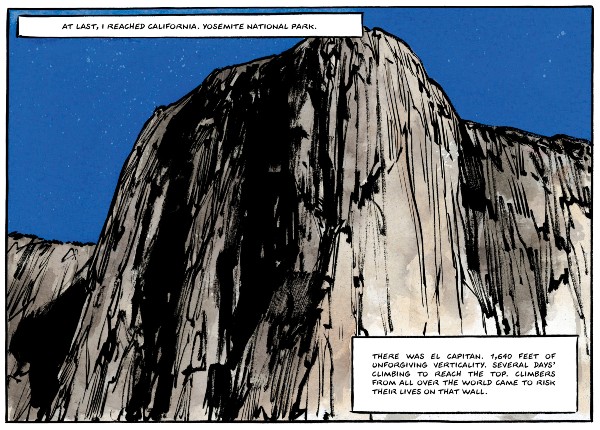

Artistry and mountain climbing might seem like radically different interests. One is physical and dangerous, requiring tactile grasping with Nature, while the other is quiet, contemplative and achieved through reflecting on Nature in solitude. Yet for Romantic poets, Nature was a visceral sensory experience that artforms could only aspire towards. And for Jean-Marc Rochette, mountains represented “beauty in their purest form”, an aspect of the Sublime which he not only marvelled at in art-museums but physically grappled with throughout this childhood of mountaineering. Altitude is Rochette’s autobiography, co-written with Olivier Bocquet and translated to English by Edward Gauvin, which recounts Rochette’s experiences and adventures in mountain climbing from its awe-inspiring heights to the rough and coarse lows.

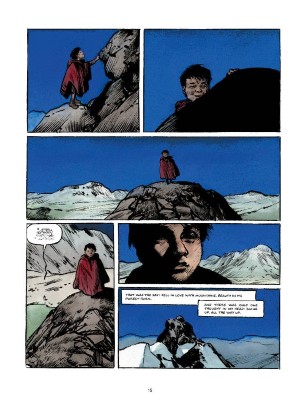

Rochette’s rough and solid artwork does a good job of capturing the varied terrain and climbing-gear needed for mountaineering, as well as the more domestic scenes as a young Jean-Marc develops his interest in climbing. The opening chapter – which sees Jean-Marc entranced by a painting before becoming transfixed by a mountain-peak on a later hike – does particularly well at showing him becoming moved by the sheer power of the images. Unfortunately, the script and dialogue are less stirring, making the first half of Altitude somewhat a slog as Jean-Marc runs through generic conflicts with authorities who disapprove of his activities, or detailing the climbs themselves without much depth. The writing of Altitude is not awful, but it’s unmemorable and overall comes across as rather flat. Jean-Marc’s cold-hearted mother has some interesting moments, but is not given enough depth or character to break away from Jean-Marc’s vilification and feel ‘real’ (Rochette himself dedicated Altitude to his mother, so his own feelings are likely more complicated than what comes across).

Rochette’s rough and solid artwork does a good job of capturing the varied terrain and climbing-gear needed for mountaineering, as well as the more domestic scenes as a young Jean-Marc develops his interest in climbing. The opening chapter – which sees Jean-Marc entranced by a painting before becoming transfixed by a mountain-peak on a later hike – does particularly well at showing him becoming moved by the sheer power of the images. Unfortunately, the script and dialogue are less stirring, making the first half of Altitude somewhat a slog as Jean-Marc runs through generic conflicts with authorities who disapprove of his activities, or detailing the climbs themselves without much depth. The writing of Altitude is not awful, but it’s unmemorable and overall comes across as rather flat. Jean-Marc’s cold-hearted mother has some interesting moments, but is not given enough depth or character to break away from Jean-Marc’s vilification and feel ‘real’ (Rochette himself dedicated Altitude to his mother, so his own feelings are likely more complicated than what comes across).

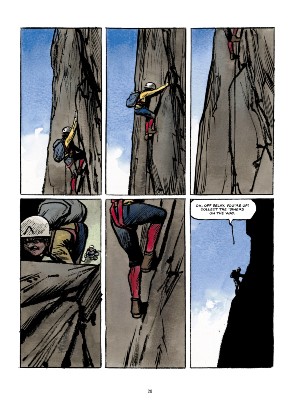

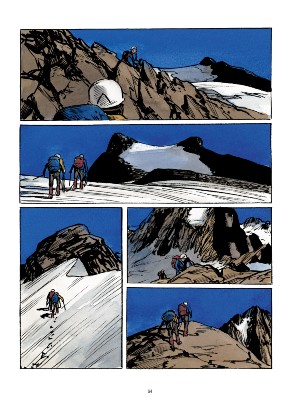

As for the mountaineering itself, Altitude also gives a mixed-bag. Each climb is impressively detailed but after a while they begin to feel rather lacklustre. Late into Altitude Jean-Marc complains about the boring statistics of art-history classes; “art is subjective. If the history of art is just being objectives about artists and their works, count me out”. Yet this is exactly the approach which weighs down so much of Altitude’s content. It overwhelms readers with names of slopes, terrains, climbers, equipment, throwing around terms like “crampons” and “verglas” and “glissalding”, and detailing the difficulty and times of various routes. But it all feels a bit myopic, so enamoured with the facets of mountaineering it often forgets to make the actual experience engaging. Plenty of books and films have made me interested in worlds I am unfamiliar with, but Altitude frequently gets so lost in the reminiscences of mountaineering it does not guide the uninitiated along.

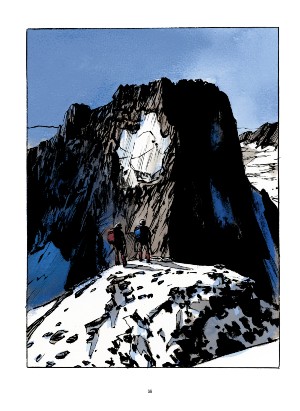

But Altitude does not always fail in this footing, as there are notable sequences which do install the sense of excitement and achievement that climbing is meant to convey. Rochette’s bold artwork, quietly strong colours and sense of scale make the magnificent mountain-top views especially swelling. Many times the repetitive climbs and jolly attitude (Jean-Marc and his friends having big laughs on these cliffs) can drain the tension, but perhaps it’s a necessary foundation for when the routine comfort of the climbs falls out of Jean-Marc’s hands.

It might be sadistic, but it’s when things begin to go wrong in the latter half of Altitude that the book starts really working. Friends and climbing-partners fall away due to adult responsibilities, and soon Jean-Marc is risking increasingly dangerous routes with people he is unfamiliar with, or even by himself. Sequences that detail Jean-Marc’s accidents and mis-steps are particularly gripping as they remind readers of how dangerous this activity is, and how feeble climbers appear next to the indifferent might of Nature. The book can be a slow-burn which doesn’t provide much insight to the mountains of its climbers, but there is something engaging and honest once it lays the ground-work and begins reaching its apex. Rochette still clearly loves mountaineering to this day, but ironically, it’s when portraying the dark and dangerous side of the sport that Altitude really soars.

Olivier Bocquet & Jean-Marc Rochette (W), Jean-Marc Rochette (A), Edward Gauvin (T) • SelfMadeHero, £16.99

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong