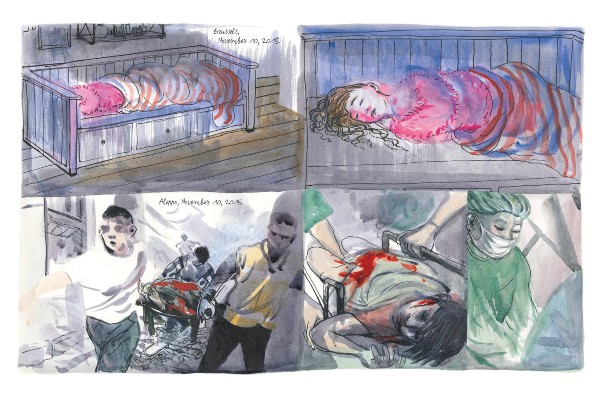

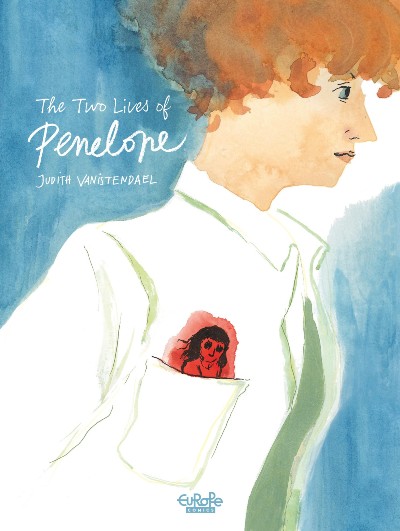

Judith Vanistendael’s The Two Lives of Penelope tells the story of a woman living two parallel lives – one as a mother, in a cosy home, with a loving husband and daughter, and the other as a surgeon in Aleppo, struggling to saves the lives of adults and children who are injured during conflict and violence. On this particular occasion, when she returns home, she realises that she has inadvertently brought something back with her – a ghost.

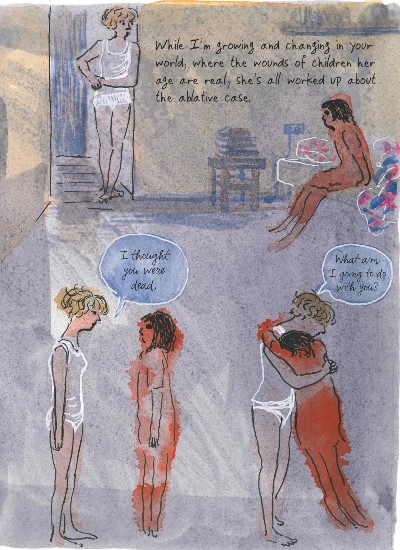

The Two Lives of Penelope tells the story of Penelope’s struggle to reconcile her role as mother with striving to continue her purposeful work. Judith Vanistendael’s artwork elevates every scene and emotion, at moments rough, vibrant, and unabashed, while at other times revealing a more gentle, tender subtlety. Indeed, the subtleties of the watercolour reveal equally slight shifts in mood: an expanding dark wash shows the distance between Penelope and her husband as they talk late at night, a tiny hint of red in the background reminds us of the ghost that haunts her, and the complete omission of line art during one scene heightens the release felt in a moment of intimacy.

Borderless panels allow contrasting events to bleed into each other, the wash of watercolour uniting the two worlds: the chaotic and the calm. Vanistendael’s linework is generally restrained, hinting at objects and people but often leaving the colours uncontained and abstract. This adds a dream-like nature to the story, which makes sense when we recall that the vast majority of it is set in in the past. With this in mind, the abstract art can be seen to epitomise the fleeting nature of this time, of this respite, of Penelope being at home with her family. Oftentimes, the more emotional dialogue is told without focussing on facial expressions but instead through a contrast with the everyday, such as the act of eating a soft-boiled egg. This emphasises the duality of Penelope’s life and how she struggles to connect to the life of her family anymore – so routine and simple compared to the fast-paced, urgent nature of her work elsewhere.

Vanistendael also raises issue of gender equality and perceived gender roles through Penelope’s internal conflict. Penelope herself considers the guilt that she is often forced to feel for her recurring absences, noting that, on the contrary, men are often praised for putting their work first and foremost. At the same time, she notes how people are concerned for her child being solely looked after by her husband, whereas they would have no issue if only the mother was around: “I’m sure that… if the situation were opposite… you never would have asked”. The Two Lives of Penelope looks at the societal role and personal significance of being a mother and calls out the disparity around parental expectations. For example, the difficulty of identifying as a mother whilst also trying to maintain the other facets of your identity is a core dilemma of this tale.

With every page brimming with beautiful, delicate artwork and an intriguing and sensitive story, The Two Lives of Penelope ignites the heart with a sense of humanity and empathy. This is what makes this story so powerful; by drawing us in with the familiarity of family life and contrasting this with Penelope’s internal conflict, we see how hard it is for those who, in helping others, sacrifice their own wellbeing, their own comfort, and their sense of family to navigate these separate realities. The duality of these lives is never fully discrete – they carry their ghosts around with them.

Judith Vanistendael (W/A) • Europe Comics, €9.99

Review by Rebecca Burke