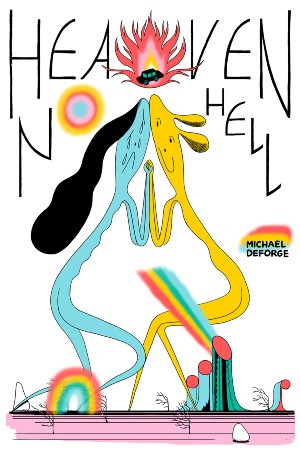

Following on from his review of Michael DeForge‘s Heaven No Hell last week at Broken Frontier, Lindsay Pereira talks to DeForge about his art, being productive during a pandemic, and the origin of his mysterious, amorphous figures…

BROKEN FRONTIER: I couldn’t help smiling at how so much of Heaven No Hell made for perfect reading during our state of quarantine. How did the pandemic affect you as a writer and artist?

BROKEN FRONTIER: I couldn’t help smiling at how so much of Heaven No Hell made for perfect reading during our state of quarantine. How did the pandemic affect you as a writer and artist?

MICHAEL DEFORGE: Thank you! I think like most other artists right now, I’ve found it pretty tough to focus on work. I don’t think it’s just the crushing despair (although that doesn’t help,) but it’s been difficult for me to write anything in the moment that I can’t imagine becoming hopelessly dated in, like, 6 months. There’s just too much to react to. A portion of Heaven No Hell was written pre-2020, and a portion written during it. Hopefully, it’s relatively seamless for the reader, but those stories feel worlds apart to me.

Anyway, I think I’ve decided to mostly embrace it and accept the fact that most of the art we’re all creating right now will be completely cringey and embarrassing to look at by the time 2022 rolls around. I draw a daily comic called Birds of Maine that really leans into it, since I’m attempting to construct an explicitly utopian world there.

BF: Familiar Face was a startling critique of technology and the impersonal nature of lives we increasingly seem to lead. How optimistic or pessimistic are you about that changing in the years to come, given what we have been through in 2020?

DEFORGE: I felt a little more optimistic about this at the start of the pandemic. I thought being tethered to our computers even more would help push us to demand a more democratic, collectively-owned vision of the Internet, but I’m not sure I really saw that happen. A small number of Silicon Valley evangelists and technocrats still have the stranglehold on these conversations. Most people recognize there’s a problem — if you look at, for instance, social media, almost anyone can pick out the parts of social media that are positive and useful, and the parts of social media that are actively making the world miserable — but have a hard time imagining any alternative aside from a handful of meagre calls for insufficient “reforms.”

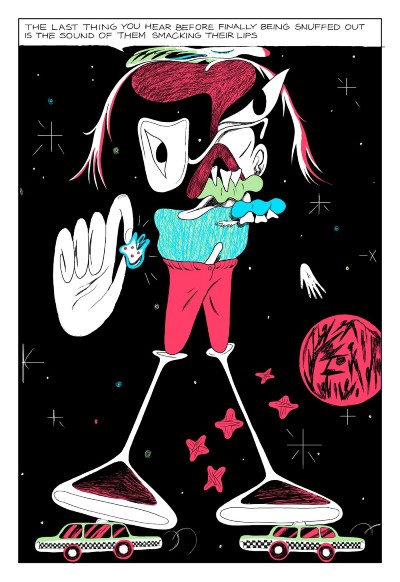

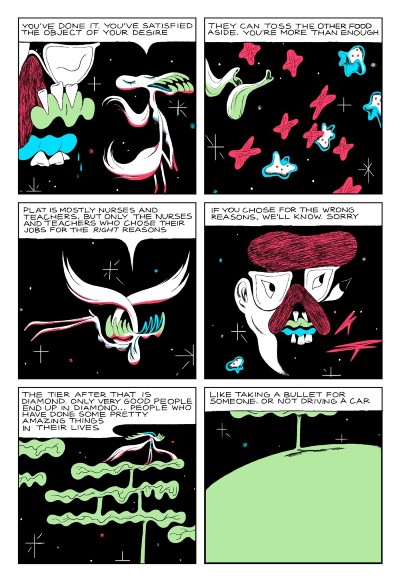

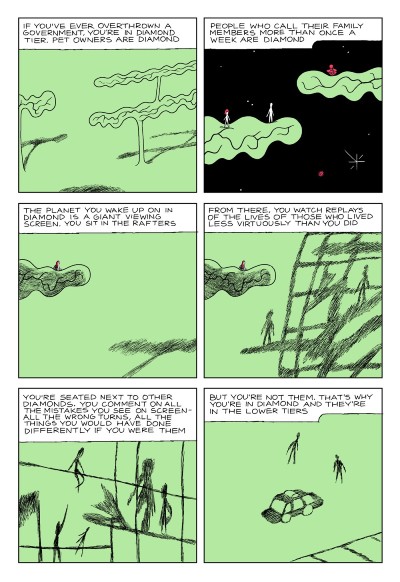

BF: The figures that populate your work are incredibly hard to describe because of how amorphous they are. I was wondering if you could talk about where they come from, and how they have evolved over the years.

DEFORGE: I’m always trying to be a more elastic cartoonist, especially with my character designs. My drawing used to be a lot more rigid, so I like paring down, blowing up, squashing, pulling or pushing figures to their limits when I’m able to. I think it’s partially because I’m attracted to that sort of elasticity in other cartoonists, and also because it’s a more joyful type of drawing for me. Making comics can be such a rigorous process that finding those small moments of exuberance can be really crucial. I hope my characters keep getting blobbier as I go.

BF: We live in a time when artists are routinely compelled to put their careers before their opinions and keep their personal views to themselves. This makes your Twitter account a breath of fresh air. Do you feel any pressure to stay apolitical?

DEFORGE: I don’t feel very much external pressure or anything. Part of that is because I think comics are kind of low stakes, to begin with, and also because I’m at a point in my career where I’ve already established myself and built up enough of a readership that I can afford to speak more freely. I know I’ve burned a non-zero amount of bridges talking about industry issues, but I’m thankfully in a place where that hasn’t completely screwed me over yet. I doubt I’d feel the same way if I had to be 20 again. The risks are much higher for artists just starting out.

BF: You have a large group of fans who love everything you do. Are there any new, exciting books by other artists you would like to nudge them towards? Something that has caught your eye and stayed with you during these last months?

DEFORGE: I confess to not having kept up that much with new comics over the past year, since I’m not able to aimlessly browse through Beguiling (a comics bookstore in Toronto) shelves the way I used to. (They’re still doing curbside pickups and online orders, of course!)

I only recently came across Mara Ramirez’s work and I think it’s fantastic. I’ve been liking Wayne Bruce’s drawings a lot — @animalhomosexuality on Instagram — and in addition to their comics, seeing Paterson Hodgson’s flyers all across Toronto has been really energizing. I love looking at Nicky Minus’ posters. Outside of comics and print, Annapurna Kumar has been making very inspiring animation.

BF: Heaven No Hell has been described as a collection of modern parables. Do you agree with that? How would you describe it to someone who isn’t familiar with your earlier work?

DEFORGE: I guess so! Short story collections are so tough to pin down, and I don’t envy my publishers who have to write the copy for them. I think a lot of Heaven No Hell is about the different ways we tend to recreate and relitigate the same traumas and regrets over and over again, which is a holding pattern I certainly find myself in a lot. But I also hope it’s funny. So, if someone is coming to it with zero prior knowledge of my work, I guess I’d tell them it’s a funny collection of funny cartoons.

Interview by Lindsay Pereira

[…] Pereira speaks with Michael DeForge about Heaven No Hell, the retroactive cringe of pandemic art, cartooning elasticity, and aiming for […]