“If someone stepped back and looked at all the times superheroes went into the afterlife, yeah, it’s ridiculous and perhaps even embarrassing.”

A. David Lewis has always had an affinity for the area where comics and religion meet. The comics scholar and writer is a student of both domains and that has resulted in a book to be released next month, American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife.

A hefty title that requires a hefty explanation of the subject matter. Lewis provided an excellent opener for our conversation: in the press release announcing the book, he was quoted saying that superhero mortality “has less to do with sales, nothing to do with spandex, and everything to do with American selfhood.”

A bold statement, but Lewis holds firm that there’s enough available data to back up those words.

A. DAVID LEWIS: Take only superhero comics published in the U.S. from approximately 1985-2010, twenty-five years. The characters travel into the afterlife with stunning frequency; besides maybe New York City or outer space, I’m hard-pressed to find any other setting that superheroes quest in as often. So, it’s conspicuous: Why are superheroes constantly journeying into the afterlife?

A. DAVID LEWIS: Take only superhero comics published in the U.S. from approximately 1985-2010, twenty-five years. The characters travel into the afterlife with stunning frequency; besides maybe New York City or outer space, I’m hard-pressed to find any other setting that superheroes quest in as often. So, it’s conspicuous: Why are superheroes constantly journeying into the afterlife?

And that leads to the bigger question: Why are audiences supporting stories of characters frequently going to the afterlife – and returning? Perhaps the overall question could be why people are reading the superhero genre to begin with, and how is it happening at an industry-sized scale?

All these questions lead me to the same answer: The audience follows superheroes, follows them into the afterlife, follows their endless narratives because it serves the audience itself. Superheroes give readers something – perhaps hope in morality, perhaps a sense of escapism, or perhaps (and here’s where religious studies, literary theory, and the social sciences all lean) perhaps its input into their own sense of selfhood.

Superheroes may do far more than influence our morality; they may help us determine what it means to be individuals.

Meanwhile, Amazing X-Men #8 makes my whole argument in SUPERHERO AFTERLIFE for me. pic.twitter.com/o2ptZw0rIp— A. David Lewis (@adlewis) June 4, 2014

Are you also saying that sales have absolutely nothing to do with the endless dead/resurrection cycle?

No, no, it has less to do with sales than with this narrative cycle. Of course there are those big event deaths and returns that influence sales: Brightest Day, “The Death of Superman,” Avengers Disassembled, Final Night, Day of Judgment, “Wolverine Goes to Hell.” In fact, right now, we have The Death of Wolverine unfolding with next-to-no chance that he won’t be back by, say, 2016. And, yes, in those high-profile instances, it’s likely being done for the sales income.

But what I don’t think enough people recognize is how much more common these storylines are, beyond the high-profile events. When Hawkeye and the Thunderbolts headed into the afterlife to liberate to liberate Mockingbird, the issues didn’t fly off the shelves. Nor did the Hellstorm mini-series, necessarily, or the Justice League of America 80-Page Giant 2011. As a genre, superheroes keep returning to this setting and the dilemmas associated with the afterlife far more often than just sales-driven motivation would dictate. It’s almost, dare I say, a compulsion.

A scene from Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man #6 where Peter Parker jokes about coming back from the dead.

Does this cycle hurts the validity of the superhero genre among readers in the long run as they grow older, or do most people accept that it’s an inherent part of the genre?

I think, if left unexamined, it hurts the credibility of the genre when taken at large. That is, if someone stepped back and looked at all the times superheroes went into the afterlife, yeah, it’s ridiculous and perhaps even embarrassing.

But that’s only if someone both looks at the big picture and then fails to ask: Why?

If readers, particularly older readers with (I hope) the advantage of experience and its wisdom, take that extra step to analyze, as I have attempted to do, just why these stories keep recurring, then they may arrive at something much more satisfying and enlightening—the notion that this critical mass of superhero afterlife comics is coming about as readers’ desire and creators’ impulse for investigating the self.

What are we if we’re not (only) our bodies? What layers do we have to our selves?

What led you to write this book? Was it a combination of ‘the sign of the times’ so to speak, combined with your in-depth study of the comics medium over the years?

My interest grew rather organically, I think. That is, during my doctoral work at Boston University, I was growing more and more attracted to both thanatological and eschatological research; I was interested in what religions thought about death, about the afterlife, and about the end of existence. Since my degree was in Religion and Literature, I was especially drawn to the stories and narrative each religion told about these subjects.

Long story short: I was finding similar stories being told with remarkable frequency in my own comic book reading. Hal Jordan as a disembodied spirit? The Thing goes to Heaven? Lobo released from his prison in Hell? I was seeing it everywhere and, the more I looked, the more I found.

On top of that, I discovered very few people talking about it—talking about the why of it all. So, I was compelled to cap my doctoral studies with the most intensive analysis I could personally bring to it.

Have you spoken to any of the creators responsible for the stories you’ve mentioned?

Yes, I have, though, admittedly, I didn’t hit any of them over the head with the full weight of my doctoral thesis. Instead, I’ve simply asked for their thinking and reasoning when it came to writing certain stories.

Folks like Mark Waid and J.M. DeMatteis have been wonderfully forthright, and they even assented to writing blurbs of support for my book! I’ve also spoken briefly with folks like Jim Krueger (Earth X trilogy) and Brian Michael Bendis (“Avengers Disassembled”) over the past few years.

Essentially, they each confirmed that there was no “template” they individually followed, necessarily, regardless of whatever interesting similarities I was finding between the whole subgenre of superhero afterlife stories.

Unfortunately, I never really got to speak to Mike Wieringo in depth before he died, though I do have an original page of his from the Fantastic Four: Hereafter storyline that I cherish. I think his art, dating back to his work on The Flash, had a great influence on me; he’s one of the men to whom I dedicated the book. I’ve also been collecting original art like Doug Braithwaite’s pencils from Paradise X of heaven and the hereafter.

I would still like to follow up once the book is out with Warren Ellis and Alan Moore, perhaps Geoff Johns and Jason Aaron, as well.

The one legendary character that has remained dead for quite some time is Jean Grey, though Marvel’s found a way to bring her back by dropping the original X-Men in the present. Why do you think the Jean Grey that died in Grant Morrison’s New X-Men hasn’t been revived yet?

It’s been some time since I read Morrison’s New X-Men, but, if I remember correctly, after Jean died, she was subsequently located in some extra-dimensional “white-hot room,” no? That is, she achieved some sort of cosmic afterlife and, from there, nudged Cyclops to allow himself a romance with Emma Frost. Am I misremembering?

At any rate, I think two factors have held back Jean’s wholesale resurrection. As much as “young Jean” serves as its own manner resurrection for the time being, the comic book Jean is operating under the much higher-profile death of the cinematic Jean Grey in the X-Men movie franchise; Hugh Jackman’s The Wolverine might have needed Jean to stay dead (what a funny idea, huh? “stay dead”) for its plot to work at all well. Of course, she’s now been restored by the Days of Futures Past movie, so that may unlock her character in comics.

But, the second reason for her lack of resurrection is, frankly, how overt this trend is becoming. That is, with “normal” superheroes repeatedly coming back from the dead (e. g. Green Arrow, Hawkeye, Aquaman, etc.), I think audiences may be a bit leery of characters whose main trait is immortality: not just Jean, but Wonder Man, Resurrection Man, Mr. Immortal, etc.

To some degree, I think this might explain Marvel’s current “Death of Wolverine” storyline – “look folks, he can die!” – even if we all know it’ll ultimately be, heh short-lived.

Non-believers of comics as an art form may find the academic study of the medium awkward, perhaps even ‘non-academic’. But you’re going a step further and mixing the study of comics with the study of religion. How do your students respond when you tie the two together in class?

Of course, it depends on the class and the campus. On occasion, I might have a harder time with students at a science-geared school versus those at a humanities-based, liberal arts college. But, on the whole, the students are fairly accepting of comics as a legit medium for analysis.

In fact, some of them find it almost quaint! The average millennial has grown up in a media environment where they were constantly seeing reports of “comics coming of age,” so I don’t think they’re at all entrenched or set against it.

Rather, it’s the dyed-in-the-wool, old-school academics who maintain any remaining opposition to Comics Studies. We, the scholars who work with/in comics, are getting more positive attention than ever before.

I think we’re on the cusp of a real break-through in terms of Comics Studies specialties and departments becoming a reality on university campuses nationwide.

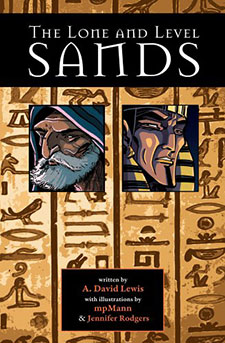

Most of your comic stories, from the early Mortal Coils to The Lone and Level Sands and Some New Kind of Slaughter have all had religion or existentialism as one of their core themes. Do you fathom yourself ever writing a different kind of story?

In The Lone And Level Sands, A. David Lewis retells the Book of Exodus, drawing on the Bible and the Qur’an.

Oh, I’ve dabbled in plenty of other themes and stories here and there. I’ve done some superhero scripts, a romance story, and my stab at an espionage adventure became the Empty Chamber series I did with Jason Copland (POP) back in 2006.

In fact, I’ve had the chance to return to some historical fiction: Back in 2007, I was part of editor Jason Rodriguez’s Postcards: True Stories That Never Happened collection, and now I’ve written a new story for his Colonial Comics: New England, 1620-1750. The story, featuring art by JT Waldman, is about the first permanent Jewish settlement in America, part of Newport, Rhode Island.

But, sure, I suppose I do gravitate to existentialism and religious lore for much of my creative work. In fact, my first published work in comics was for the small press publisher Committed Comics who wanted a story concerning Barabbas, the bandit released by Pontius Pilate instead of Jesus in the New Testament.

I suppose it’s always been in my proverbial wheelhouse!

Are you working on a new graphic novel at the moment?

For the first time in years, yes, I am! It’s still a rather embryonic project at the moment, but I’m very excited about it. The plan is to take a Golden Age superhero and reexamine him with, you guessed it, a religious/existentialist lens. However, it’s like nothing I’ve ever worked on!

American Comics, Literary Theory, and Religion: The Superhero Afterlife will be published by Palgrave Macmillan on November 19, 2014. You can pre-order a copy on Amazon. For more on A. David Lewis, visit his website at captionbox.net.