To say that Alex de Campi is unflinching in her approach to creating comics would be akin to saying Warren Ellis is a little skewed: neither statement does their subject real justice. Whether putting the screws to a group of coddled, first-world millennials on an ill-fated bus trip to the Mexican outback or drawing attention to Wonder Woman’s cellulite in the digital pages of Sensation Comics, de Campi isn’t one to pull her artistic punches.

It is this dedication to courageous, original storytelling that informs every comic she’s put her name to, from the seminal Smoke/Ashes to the all-ages whimsy of My Little Pony. In No Mercy, her new creator-owned series from Image Comics, de Campi teams up once again with talented and ultra-popular trailblazer Carla Speed McNeil (Finder) for one of the most harrowing, grueling journeys in funny books today.

Or “not-so-funny books”, as the case may be.

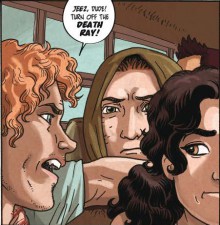

From its biting and at times painfully accurate social commentary to its visceral, no-holds-barred realism, No Mercy is a disturbing thrill ride that taps into first-world travel phobias, while shining a glaring spotlight on our over-reliance on technological comforts in our day-to-day lives. De Campi and McNeil challenge our perceptions of what it means to be safe outside our borders, and more importantly, in our own skins.

Broken Frontier had the opportunity to speak with the gracious de Campi about her own travel experiences, culture shock, and the changing language of comics.

No Mercy isn’t your typical comic book story; its plot and cast set it apart from the majority of books on the shelves today. Could you give us a little insight into the plot and some of the major themes you want to explore in the series?

ALEX DE CAMPI: Isn’t it a typical comic book story? Sometimes I feel I live in a bubble and/or am a terrible solipsist. In a way, I suppose No Mercy appeals to my minimalism. Take as little as you can, and make as thrilling a story as you can. No powers, no talking animals, no secret government agencies that employ supernatural creatures to fight crime. No time travel (this year’s trend).

ALEX DE CAMPI: Isn’t it a typical comic book story? Sometimes I feel I live in a bubble and/or am a terrible solipsist. In a way, I suppose No Mercy appeals to my minimalism. Take as little as you can, and make as thrilling a story as you can. No powers, no talking animals, no secret government agencies that employ supernatural creatures to fight crime. No time travel (this year’s trend).

Just kids. Just a trip. No Mercy seems mainly to be a good old-fashioned disaster story: 20 kids go on a service mission to Central America before their freshman year of college, and A Tragic Event quickly occurs. Things get worse from there. The book starts off being about privilege, on many levels, and then over time, slowly and quietly morphs into being about the nature of a tragedy, and how it never really ends.

Whistleblowing, cover-ups, an institutional closing of ranks, the all-American blame game… Some of these kids will be plaintiffs in court cases for the rest of their lives. What’s most interesting for me is how the greatest tragedies, the worst parts of the story, happen after some of the kids come home.

This is a series that taps into an almost primal fear first-worlders like ourselves have of traveling to third-world countries, where poor infrastructure, unstable political climates, and crime and corruption are far below the standard of living we are used to. Have you ever experienced the same sense of culture shock that some of the cast struggles with on their journey?

I spent a little over 15 years living outside the US – five in Hong Kong, a year in Manila, some time in Latin America, a decade in London. I’ve been places where I exist in a cone of silence as I don’t really speak the language. I’ve also been that privileged white kid behaving abominably in foreign countries. I’ve also stayed alive through sheer luck rather than judgement.

But also, I’ve realised often how well certain things work in what we call the “third world”: healthcare is often fantastic; sometimes public transport networks are amazing (in Tunisia, for example); kids in this third world are often better educated and speak more languages than we do; the mobile phone situation is like 200% more sane in terms of cheap, flexible contracts (because the landline situation is often terrible).

And some places are more dangerous for white people than others. Though actually the majority of the characters in this book are non-white, they are gringos, and they’re in a bad country to be a gringo.

How do you think you would react if you ever found yourself in a similar harrowing situation as the poor kids in No Mercy?

The me of, say, 1998 would have been amazing. The me now? I’d probably be toast. I am quite organised and level-headed in times of disaster/stress, but I’m such a homebody now I’m sure I’ve lost all my elite travel skills.

Carla Speed McNeil and yourself enjoy a wonderful creative synergy on No Mercy. It truly feels like one person wrote and drew the comic. As an accomplished writer in her own right, as seen in works like Finder, what have you learned from Carla as a storyteller working on No Mercy, one of your longer-form projects?

It’s just wonderful that Carla has my back. This is our third project together, after Smoke/Ashes and My Little Pony. We pass dialogue back and forth, and she pencils in word balloons (artists! DO THIS!) and tweaks/improves dialogue from my scripts in them as she goes.

Both of us are inveterate tinkerers – why go over a line of dialogue once, when you can go over it five times? Her lettering is also sublime, and I try to replicate her pencilled hand-lettering effects in my rather unhinged lettering for the book. And me? I just try to write a book that she’ll enjoy drawing. It’s working so far.

You seem to prefer lettering your own comics. Where does this preference come from and what are some of the benefits of lettering your own stories?

It means you can be a little lazier/sketchier at initial script stage, and still catch the cruddy bits before anyone sees them (there are always cruddy bits). It means you can truly hand-tailor the book to the art when it comes in – I find this is especially important with sound effects, either adding more in or dropping them for best storytelling effect. I really enjoy the lettering process.

Lettering is incredibly time-consuming for me, though, as I freehand all my balloons in Adobe Illustrator, adding in all sorts of odd effects. I letter maybe one page of No Mercy every two hours. It’s a hopelessly inefficient way of working, but I love the craft of it.

I love integrating words into the art so it’s a coherent whole, not just these sterile blobs and lurid, gradient-happy SFX crapped onto the nicest bits of the page without empathy or shame.

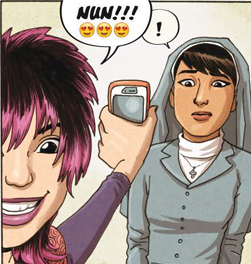

As a letterer, you aren’t afraid to push the boundaries of the craft, using icons and emoji in place of words – especially in the character of “the Quiet Kid”. How important is it for readers and creators to update their perception of what constitutes comics lettering, in the face of social media’s massive impact on the way we communicate with each other on a daily basis?

As a letterer, you aren’t afraid to push the boundaries of the craft, using icons and emoji in place of words – especially in the character of “the Quiet Kid”. How important is it for readers and creators to update their perception of what constitutes comics lettering, in the face of social media’s massive impact on the way we communicate with each other on a daily basis?

I love language. But I love language as a fluid, quicksilver thing that has abbreviations and icons and dialect and slang, and new expressions being forged every day in the heat of the moment. So much of this book is about how kids communicate with each other, I just tried to represent the way me and my friends communicate on social media as that will still be hopelessly behind the kids, but not wild enough to frighten the horses, yes?

And emoji amuse me. They’re fun. Why not use them? The fun of a comics speech balloon is, we are still reading it. So emoji and chatspeak and acronyms look right in them.

“The Quiet Kid” is one of my favourite characters of No Mercy, so far. He seems to say and do far more in his silence, than the other kids. How do you go about building such an eclectic ensemble cast without letting a prominent trait such as his define him?

It’s funny. Everyone has a different favourite kid. At first we worried this might be a problem for the series, in that there is no clear hero. Then… readers seemed okay with it. They had their favourites, they had the characters they wanted to see die horribly, and then we do bad things like make some of the die-horribly characters actually reveal themselves to be okay or at least relatable, so you may change your opinions of them.

One thing we really tried to avoid was having kids fall into obvious categories – the goth, the nerd, the jock, the popular girl, etc. The kids are all more nuanced than that. And they’re out of their usual milieu, so they will be a little more toned down than if you met them with their crew of high school BFFs.

So yeah, Quiet Kid is pretty awesome. I just wrote him as I thought might happen if meeting him in real life. There are a few other kids – Deshawn, for example – who we don’t even really get to know until we get into issues 7, 8, 9… not that he’s hiding anything, but certain stuff doesn’t just come up in conversation. You assume you know them. They assume they know each other. This is not necessarily true.

So yeah, Quiet Kid is pretty awesome. I just wrote him as I thought might happen if meeting him in real life. There are a few other kids – Deshawn, for example – who we don’t even really get to know until we get into issues 7, 8, 9… not that he’s hiding anything, but certain stuff doesn’t just come up in conversation. You assume you know them. They assume they know each other. This is not necessarily true.

Finally, after only one issue, things look pretty grim for these poor kids…Will they ever catch a break? Is there really “no mercy”?

I just finished writing issue 8, our last before a break. Nope. No mercy. That issue has two hardcore mic drops at the end. They’ll leave a dent. I want to leave them cursing us, while we take off on break.

(But to be serious – there is joy. There is happiness. There is hope. There are even poop jokes. All of this, of course, makes the bad turns so much worse.)