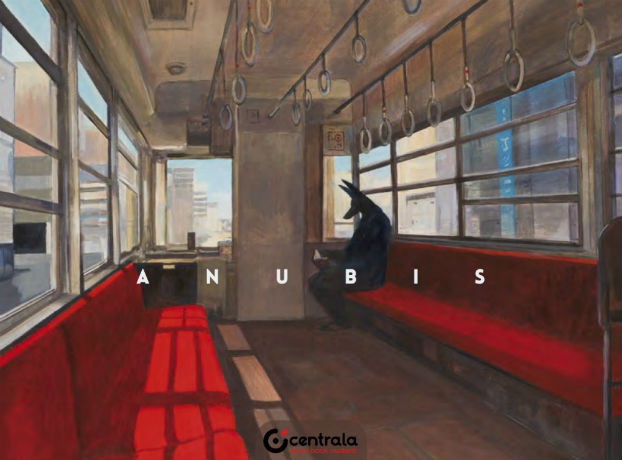

Anubis, Egyptian God of Death, hangs out in dark corners, watching, then goes to the beach, the museum, the aquarium, visits the set of Twin Peaks, stairs at you out of a beautifully painted image and asks you what you are doing with your life…

From Centrala, Anubis is a cumulative painted comics meditation on the absurd and poignant nature of existing in the modern world, where image and experience so often blur and overlap. Krakow artist Joanna Karpowicz’s paintings bring the viewer the familiar aching pathos of identifying deeply yet remaining at a distance from the lives and stories we see around us, and through screens big and small.

Let’s not talk about the fact that the postperson bent my copy of Anubis in half when they shoved it in the post box. That is not the fault of the publishers, it is the fault of the postperson. Bent in half it is still, of course, a beautiful book. Whether or not it is to be considered a ‘comic’ is a debate taken up in earnest in the afterword by Sebastian Frackiewicz. The Polish cultural critic makes much of the emotional territory between the fine and sequential arts that Karpowicz’s work so elegantly straddles, mentioning visual references to a wide range of popular culture texts (Twin Peaks, Miyazaki, Edward Hopper), although to my mind failing to mention one of the most obvious visual echoes that is present throughout the book. Does Anubis not, with his dark menacing silhouette, broad shoulders and pointy ears atop his head resemble Batman a little? OK the ears are considerably longer than we usually see the caped crusader donning, but still, if this is a comic, that’s the analogy I would be reaching for.

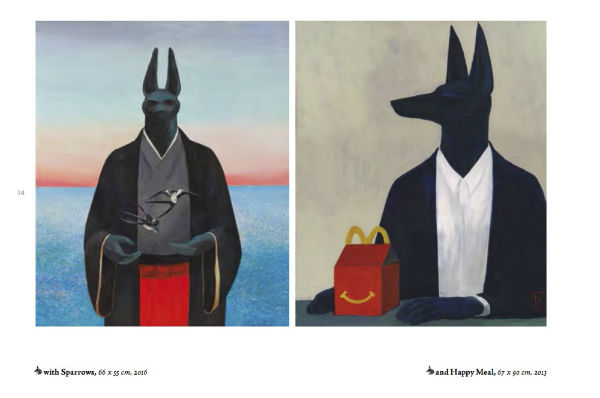

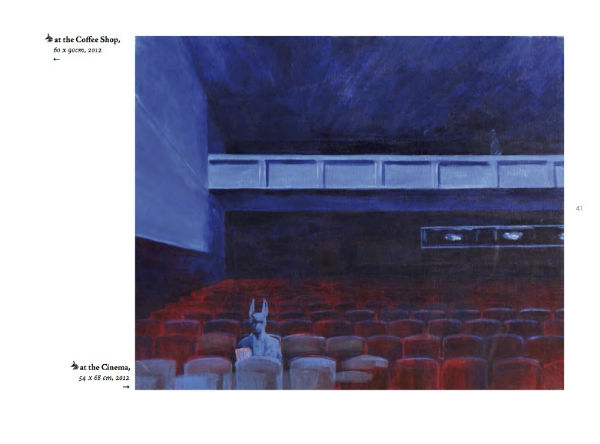

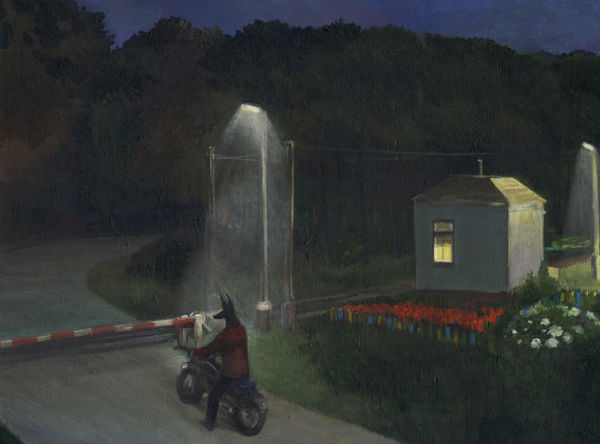

Of course Anubis is not Batman, he is “a mythical Egyptian god who safely conducts the dead to the other side”. He features in every one of the paintings presented sequentially in the book, sometimes more visibly than others. He stands alone in a dark aquarium, contemplating the manta rays, he lurks in shadows behind train platforms, and in doorways. He is the concierge at ‘The Overlook Hotel’, the audience of a lonely ‘Burlesque Queen’, he joins a circle of dancing children in the woods and has a picnic with a view of Clifton Suspension Bridge.

The mundane specificity of such a scene makes me assume that there must be many references in these pictures that I am missing. Without a window into the artist’s brain, it is hard to tell how many of these paintings are direct echoes of the world, art or movies. Some seem deliberately generic, while others have very clear visual links to specific cultures – most obviously America and Japan . The clothing and architecture often appear dated, but not consistently enough to pin the action to a particular decade, or even century.

The more I flip back and forth through the book, the greater my affection for this dog of death becomes. He gets everywhere. Which is I suppose the point, but seems reductive of what is a great, subtle accumulation of images. As a body of work, Anubis is nothing short of a masterpiece, achieving arguably what can only be done by an accumulation of images – what has been called the aim of all Art – a mirror of reality. But I’m still not entirely convinced it is a comic. I love that it is a book, putting all of these paintings in a room to be perused in a less controlled order might be an even better way to experience the series, but would inevitably be less accessible and less re-visitable.

In his epilogue, Frackiewicz bemoans the graphic novel medium for not embracing more avant-garde unstructured approaches to narrative. In as such this is a comic in the way that Koyaanisqatsi is a film. Arguably it would work just as well in a number of different orders. In fact I’m not a fan of the very first page being ‘Tribute to Nighthawks’ – a very clear and straightforward pastiche of Edward Hopper’s famous painting. Having this as the first image made me expect the rest of the book to be full of art history references just as clear, which (spoilers) it really isn’t. As I said, some of the allusions are obvious – such as the literal recreation of the Twin Peaks town approach shot, with Anubis proceeding creepily towards the viewer. But ‘Tribute to Nighthawks’ is the only piece that acknowledges its reference in its title, and many of the others are not clear at all in their allusions and origins. Perhaps beginning with this painting is supposed to be a clue – look for visual echoes in these paintings, because there is more here than what you can see. Even when there isn’t.

Which really is a great metaphor for life and all isn’t it? I would argue that this is far more than a good old-fashioned momento mori/”death is always with us” artwork. This is a story without time that is about being timeless. Death is always with us of course; at the beach, in the woods, at the all night café, in the museum, at the hotel check-in desk, at the LA swimming pool. But more importantly life is always with us, messy, varied, culturally specific, generically popular cultural referenced and totally individual. You cannot walk through this world without a rich, visual internal monologue of reference points, which is how good art is able to communicate on both the universal and personal levels simultaneously. Karpowicz has tapped into that global cultural imagination in a very beautiful way.

We bring our viewpoint to everything we experience. Anubis is with us every step of the way, and so is Batman.

Joanna Karpowicz (A) • Centrala, £12.00

Order online here

Review by Jenny Robins

[…] as a justification for hate that often evoked pseudo-science.” * Jenny Robins looks at ANUBIS by Joanna Karpowicz, which “is nothing short of a masterpiece, achieving arguably what can […]