There’s something about South Korea that doesn’t always make sense to an outsider. On the one hand, an increasing number of its cultural assets have become striking examples of soft power, from award-winning television and movies to the inescapable force that is K-pop, its reputation as a technology powerhouse to TikTok videos on its food. On the other hand lie inexplicable issues related to gender inequality and misogyny, complicated censorship laws, and a history of political repression. Art, one imagines, becomes the only viable means of navigating and expressing these opposing narratives.

Yeong-shin Ma presumably knows these waters well. South Korea has had conscription rules in place since 1957, requiring male citizens between 18 and 35 to perform compulsory military service. He began working with graphic novels only after completing his service, and the book that brought him acclaim was, surprisingly but tellingly, about four middle-aged women — the kind of people who simply don’t feature in the flashy South Korean art occupying centre-stage on Netflix and Instagram.

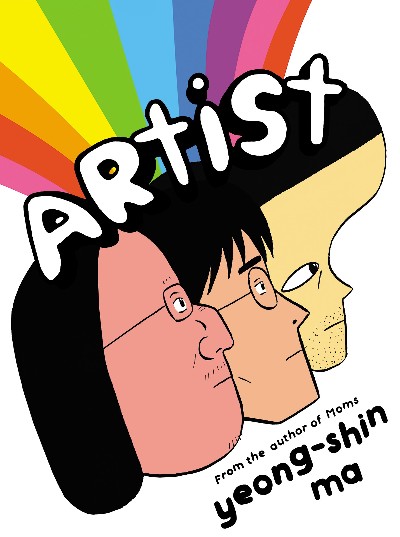

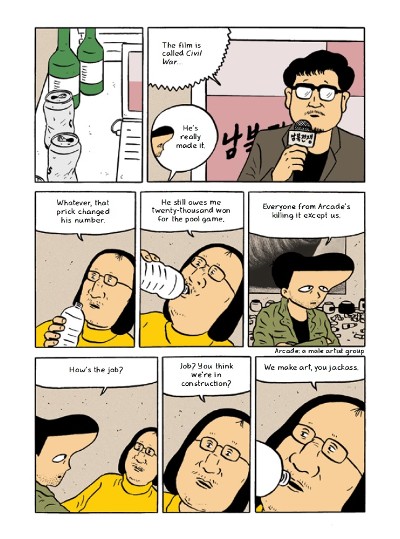

Moms was an intimate, powerful look at marginalised lives, full of poignancy and humour. He brings that same deftness of touch to Artist, which focuses on three South Korean men in their forties, gently stripping away the bluster to reveal their insecurities and perceived inadequacies. What emerges is a compelling portrait of male friendship as well as a nuanced critique of how attitudes towards art are shaped by society. It gives readers an interesting glimpse of life in a country that has emerged in our post-pandemic world as a primary exporter of pop culture and entertainment.

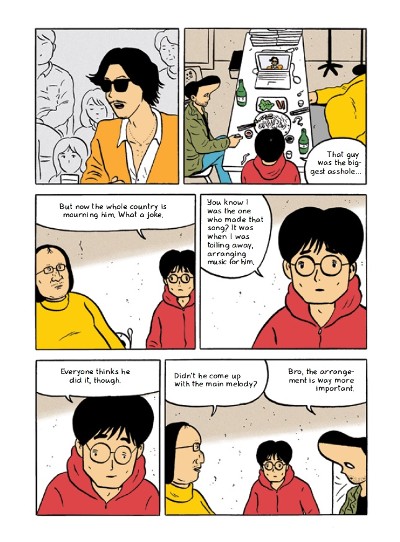

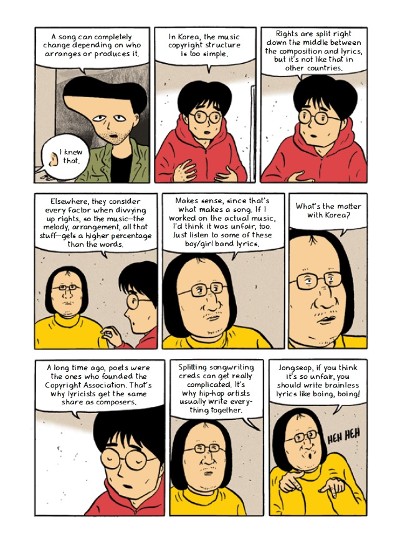

The men — 44-year old writer Shin Deuk Nyeong, 46-year old painter Kwak Kyeongsu, and 42-year old musician Chun Jongseop — exist in a world that, they feel, has failed to recognise their worth. For artists, it is a feeling as old as time, and Yeong-shin Ma introduces the tantalising prospect of success for one of them to show how his characters respond and subtly change the way they behave in its aftermath. Rolled out over 600 pages, this seems like a daunting prospect but, to translator Janet Hong’s credit, the banter is casual and flows easily, in a vernacular that doesn’t seem stilted or forced.

Hong’s work becomes more important when it comes to dialogue that shines a light on everything from the significance of last names in Korean culture to definitions of good art. These arguments presumably help Yeong-Shin Ma arrive at a sense of what he hopes his body of work will eventually convey. There is also some pointed commentary on prejudice and exploitation of labour, poking holes in systems that routinely escape attention in the glare and glamour of K-dramas and K-pop. It is in these moments that one can appreciate the larger picture that Yeong-shin Ma’s characters allude to.

Koreans refer to comics and cartoons as Manhwa and, unlike manga, offer characters with unrealistic facial features (which explains the way foreheads are depicted in Artist) and realistic bodies, paying much attention to backgrounds and clothing. Artist doesn’t always stick to this format but still acknowledges the form’s roots in political and social commentary.

One sour note here is the relative shallowness of female characters, given the richness of their predecessors in Moms. Their interior lives don’t seem to matter in Artist, which is sad because a counter to male perspectives on the commodification of art could have enriched the narrative. Also, the extended notes on law and history don’t always fit in, making for some clunky passages. That said, this is still a great follow-up from a writer who clearly has a lot to say about his corner of the world and isn’t afraid to poke around its deepest, darkest corners.

Yeong-shin Ma (W/A), Janet Hong (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $39.95

Review by Lindsay Pereira