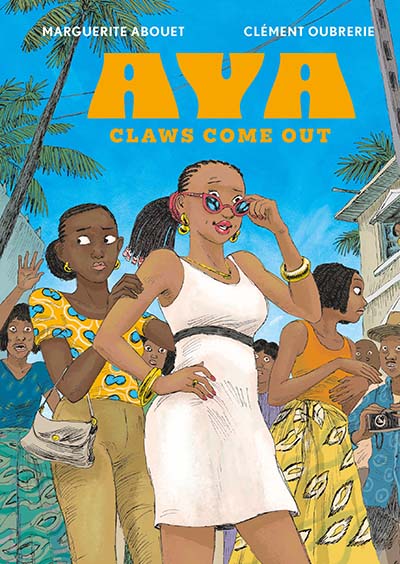

New stories about Aya, Bintou, Adjoua, and their families: if that’s not a great start to a new year, what is? Any happiness associated with this news will be undeniably restricted to those familiar with Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie’s older stories in the Aya series, but Aya: Claws Come Out still manages to stand on its own, if only up to a point.

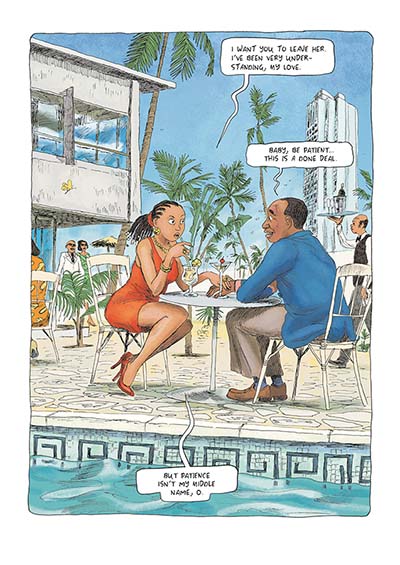

Where Aya: Life in Yop City introduced us to this colourful cast, and Aya: Love in Yop City gave us deeper insights into life on the Ivory Coast in the 1970s, Claws Come Out is darker, and has a world-weariness to it that wasn’t as obvious in the earlier books. Part of this could be ascribed simply to the fact that our heroines are all grown up, although they did grapple with some serious familial and societal challenges the last time we met them. What these new stories depict, however, is the beginning of a slide for the Ivory Coast’s golden age.

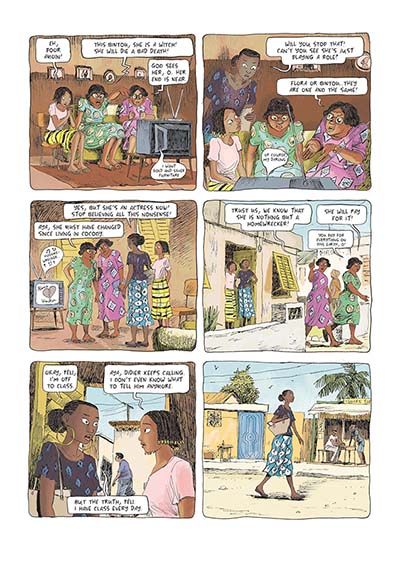

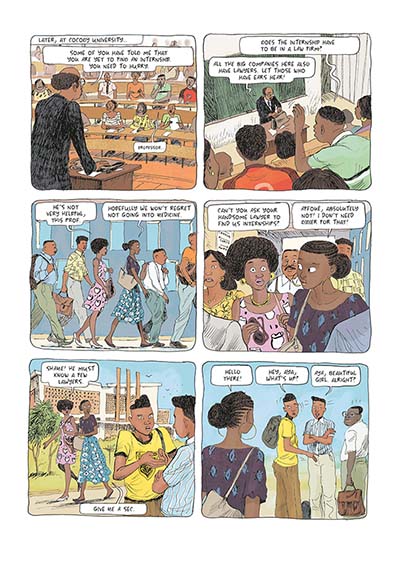

Students of history know that the country’s good fortunes began to turn by the end of the 1990s, just before the outbreak of two civil wars, and although there are no outright references to politics here, it’s hard not to notice a certain hardening of perspectives. The locals are no longer as fun-loving; there are references to serious issues such as a housing and funding for education; and even the passersby that come into Aya, Bintou, and Adjoua’s orbit appear to be more antagonistic than warm.

Students of history know that the country’s good fortunes began to turn by the end of the 1990s, just before the outbreak of two civil wars, and although there are no outright references to politics here, it’s hard not to notice a certain hardening of perspectives. The locals are no longer as fun-loving; there are references to serious issues such as a housing and funding for education; and even the passersby that come into Aya, Bintou, and Adjoua’s orbit appear to be more antagonistic than warm.

It may be hard for first-time readers to jump into some of these narrative arcs without some knowledge of what has occurred previously. Aya and Didier’s story, for instance, may make little sense to a reader unfamiliar with the scandal that erupted in the closing pages of the last book. Similarly, Inno’s struggle for acceptance in Paris will mean nothing without a clue about his past, his failed relationship with Albert, and the latter’s own battle to accept his identity and sense of self.

What hasn’t changed, despite the introduction of a new translator in the form of Ivorian writer Edwidge Dro, is the local flavour and delightful use of aphorisms that take a while to unpack. Also unchanged is Oubrerie’s art, and his innate ability to bring neighbourhoods to life with seemingly effortless scratches of his pen. As for the story, Bintou comes to terms with newfound fame, Adjoua doesn’t have a significant presence this time, and Aya tries harder to make sense of her life as a female student in a stubbornly patriarchal society. It ends with a few cliffhangers, which is great because it promises more from the series in the future.

It’s interesting to consider what happens next, in the light of what we now know about the Ivory Coast. There were protests in 1990, followed by deteriorating relationships between ethnic groups, a military coup, and a period of turmoil that eventually gave way to economic growth and stability. To be able to follow Aya’s story across these tumultuous years would be remarkable, not simply because of what a strong character she is, but because of the love that shines so clearly through Marguerite Abouet’s memories of a place and time that has long ceased to exist.

Whether or not that happens, however, we have Claws Come Out and, for now, that is good enough.

Marguerite Abouet (W), Clément Oubrerie (A), Edwidge Dro (T) • Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95

Pre-order Aya: Claws Come Out here

Review by Lindsay Pereira