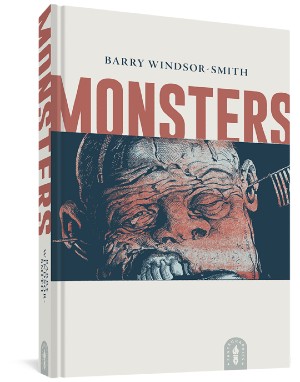

Much like the abused test-subject at its centre, Monsters is years in the making. Barry Windsor-Smith planned his macabre epic as a Hulk story, way back in 1984. Clashes with Marvel made him move the project to Dark Horse, and then to DC, before it eventually found its publisher with Fantagraphics (and Jonathan Cape in the UK). All the while, the original 22-page story was mutating into the 370-page behemoth it is today, its scope and Gothic agony overflowing. Windsor-Smith is an industry titan, who always felt uncomfortable with the mistreatment and constraints imposed upon comics artisans like himself. Monsters is his first published work since 2005, but its reach of history evokes Windsor-Smith’s potentially most famous work, the Wolverine “origin” story Weapon X.

A straightforward synopsis of Weapon X doesn’t do it justice. The story is simply Wolverine being experimented on and tortured by a shadowy government agency. But Weapon X goes beyond a generic test-tube origin, pushing Wolverine’s catatonic body past the breaking point whilst government workers dehumanise and banally chat around his cruel crucible. Monsters operates on the same fertile ground, as the stammering, young, one-eyed Bobby Bailey attempts to enlist in the army in 1964, only to be unwittingly shipped off and subjugated to the gruesome “Project Prometheus” programme. As in Weapon X, scientists and technicians bicker with each other, as the innocent child groans and transmogrifies into a bulging, grotesque creature. Monsters reinforces the horrific conditions of this experiment – the intrusive needles, the lumbering flesh, the acrid stench – with it taking “18 days and nights” (and 80 pages) to see the final Bailey; his only remaining feature his tear-filled one good eye.

A straightforward synopsis of Weapon X doesn’t do it justice. The story is simply Wolverine being experimented on and tortured by a shadowy government agency. But Weapon X goes beyond a generic test-tube origin, pushing Wolverine’s catatonic body past the breaking point whilst government workers dehumanise and banally chat around his cruel crucible. Monsters operates on the same fertile ground, as the stammering, young, one-eyed Bobby Bailey attempts to enlist in the army in 1964, only to be unwittingly shipped off and subjugated to the gruesome “Project Prometheus” programme. As in Weapon X, scientists and technicians bicker with each other, as the innocent child groans and transmogrifies into a bulging, grotesque creature. Monsters reinforces the horrific conditions of this experiment – the intrusive needles, the lumbering flesh, the acrid stench – with it taking “18 days and nights” (and 80 pages) to see the final Bailey; his only remaining feature his tear-filled one good eye.

Yet Monsters doesn’t stay contained to the body-horror of Bailey’s experiment. This narrative section curiously splits onto Elisa McFarland, the army recruiter who signed Bailey up for Prometheus, the shadowy rumours of which haunt his dreams and fuels enormous guilt over the disappeared Bailey. Bailey’s external metamorphosis parallels Elias’ prolonged emotional crisis, staying locked inside and relaying memories to his wife of childhood secret messages scrawled in comic books, and how he instantly knew about his father’s death in WW2, as if “the past and future came together.” Monsters functions like a Stephen King novel, with inexplicable magical realism overlain on its grim, tactile, historical detail. Elias possesses a quasi-spiritual “Sight” that exists alongside Bailey’s pulp sci-fi military experiments, which, as Monsters unravels, all of history appears to have converged upon.

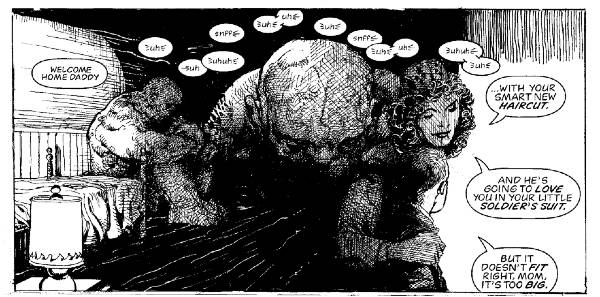

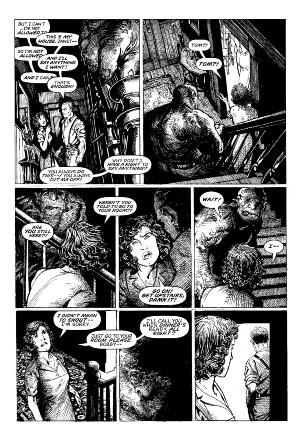

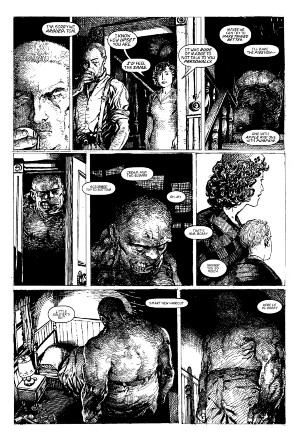

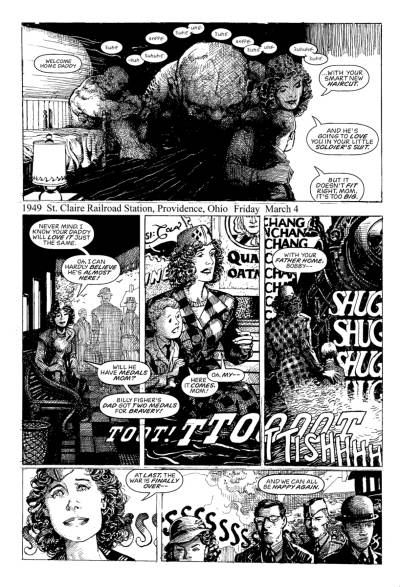

For as Monsters continues, Windsor-Smith keeps peeling backwards in time, showing the ruthless childhood abuse of Bailey after his father returned from WW2. Bailey’s gruesome physical state is only a continuation of a cyclical trauma, with several other characters being tied back to these events. Bailey’s mother, Janet, becomes the focal point in this section, following her increasingly miserable attempts to appease the hair-triggered paranoia of her returned husband. Diary entries narrate Janet’s shifting emotions, from joy to concern to fear, as Monsters’ overwhelming length wallows in the aggression and abuse Janet endures, WW2 having mutated her husband into someone unrecognisable.

But Monsters doesn’t just stop there, unfolding further into the years when Tom Bailey was away – a preserved, charming memory – and Janet waited at home, developing affections for the friendly Officer Powell. And further again, into the underground Nazi experiment which left Tom so traumatised, and would rear up again earlier/later in Monsters, the future and past coming together. Monsters scours through this timeline of generational trauma, rippling backwards through time as if to find a moment of peace, of breathing room, when the whole cascading tragedy could have been avoided.

Windsor-Smith illustrates every inch of this odyssey with ferocious verve. His use of cross-hatching creates splendid and intricate visages, from the cobwebs Elias contemplates to huge crashing trucks and fire-fights. Monsters knows how to make an impact, with Windsor-Smith often stacking panels against each other and ramping up a scene’s tension for maximum emotional strain. His lettering also deserves special mention, his cutting naturalistic dialogue flowing through and between each panel. An ultra-bold Germanic font at the start kicks Monsters on a distorted edge, and this level of unease is maintained for the rest of the reading. Monsters is too ugly to be called beautiful, but the level of dedication and skill involved is unparalleled, with moments of grace thrown in amongst the darkness too.

Monsters is an intense graphic novel. Both in the scope of its history and ambition, and the unrelenting and disturbing subject-matter. It’s sure to exhaust many readers, both in its length and its cruelty. Monsters offers some dark levity in the early stages of scientists messing around with higher-ups, using Bailey’s hideous body as a proper, but even such black comedy becomes filtered out as Monsters falls down its vortex. Even Janet’s naïve optimism waiting for her husband’s return is dampened by the cruelty we’ve already seen inflicted upon her. Monsters is tough to swallow, and perhaps a commercial editor would’ve trimmed down the excessive build-up and traumatic wallowing. Such messy human observances extend to Elias’ African-American family, who speaking in a distinct colloquial dialect that somewhat caricaturises them, even if they prove the most stable family. But such unvarnished work is what makes Monsters so singular, that reining it in would be counterintuitive. Too much painstaking detail, history and effort has been poured into it. Monsters isn’t for the faint of heart, but it’s a lumbering Gothic masterpiece of the medium; Barry Windsor-Smith’s towering magnum opus has finally, from darkness and despair, been born.

Barry Windsor-Smith (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books/Jonathan Cape, $39.99/£25.00

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong