Guest writer Joe Krawec analyses the thorny issue of “the illusion of change” in superhero comics with special reference to the Batman mythos and the unofficial Batman: The Deal webcomic published online last year…

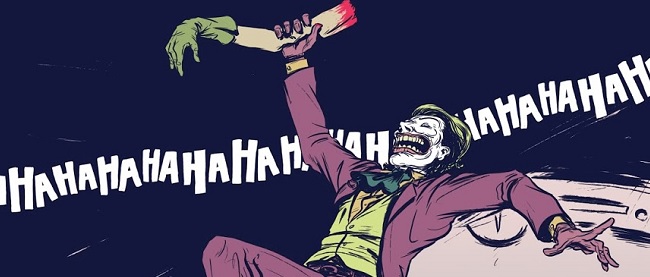

Moonhead Press created quite a stir recently with two stories that feature DC Comics’ biggest heroes – Batman and Superman. The indie publisher gave us God’s End in the New Year, which portrays an ancient Superman passing judgement upon the violence and stupidity of humanity by destroying Earth. Preceding this in November 2013, Moonhead published Batman: The Deal, which re-imagines the Dark Knight and Joker as the ultimate postmodern relationship, where their enmity is a sick game designed to test each other.

As a Batfan and researcher into comic book history, an article posted on Broken Frontier about Moonhead Press interested me. In Why ‘Batman: The Deal’ Can Never Ever Become Reality (November 2013), Evan Henry argued that The Deal is a challenge to the illusion of change, and so could never appear in a mainstream comic. The illusion of change is a theory frequently applied to publications by Marvel and DC. It supposes that superhero stories cannot offer readers real character and plot development because the serial comic medium is restrictive in two main ways. Firstly, if Batman is to appear month-in, month-out, he must remain Brand Batman: forever determined, never wrong and very much alive to sell us comics and merchandise. Secondly, any plot development that does occur can be utterly erased, subverted, and refuted via a process referred to as retcon or reboot. Thus, Marvel and DC stories are nothing more than childish-KAPOW! illusions to hide the fact that nothing really happens.

To me, it seems that the illusion of change has become a kind of penance that comic book fans must do; a birch to lash our bodies red-raw for the sin of enjoying books populated by men in tights who shout ‘Justice!’ a lot. However, the illusion of change – though appearing completely sensible – suffers when one analyses the history of a character like Batman and the mechanisms behind it. I do not deny that the theory has relevance, but its shortcomings are such that its power as a finger-wagging tool is diminished. Let me explain:

To me, it seems that the illusion of change has become a kind of penance that comic book fans must do; a birch to lash our bodies red-raw for the sin of enjoying books populated by men in tights who shout ‘Justice!’ a lot. However, the illusion of change – though appearing completely sensible – suffers when one analyses the history of a character like Batman and the mechanisms behind it. I do not deny that the theory has relevance, but its shortcomings are such that its power as a finger-wagging tool is diminished. Let me explain:

The first problem with the illusion of change comes from its ambiguity of source and the time period it relates to. Numerous websites quote it – all with different phrasing, I note – but I have yet to find a link back to the primary source. It is attributed to Stan Lee, but Marv Wolfman also gets a mention. Why is this important? Well, being sure of the source of it and the time period it refers would tell us something about the theory’s usefulness. For instance, if Stan Lee used it in relation to Golden Age comic books, say, we might consider that its relevance is limited in our post-Miller, adult readership world. If we do not nail down the when, who and why of the illusion of change, we are not engaged in a quest for truth but merely perpetuating hearsay.

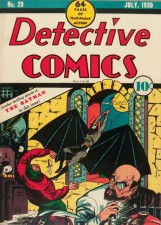

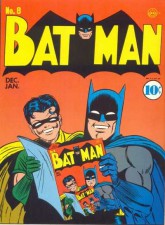

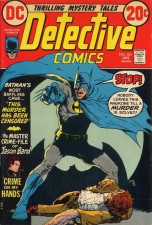

Now, say you all angrily bombard me with primary sources where Stan Lee talks about the illusion of change and that it applies to all DC and Marvel comics that have ever been and shall ever be. What then? Well, we must read such comics to consider whether we agree with him. And I, respectfully, do not. Sift through 75 years of Batman end-to-end and you will see that he has clearly changed. The Dark Knight of today is not the Caped Crusader of yesteryear. His storybook is massively varied, moving through whole lifetimes with alterations in personality, priority and result. Thus, there are numerous Batmen – the unrepentant killer of 1939, Robin’s fun big brother of the 1940s, the 1970s Detective, and so on. The reason for this links back to the arguments within the illusion theory: if Brand Batman is to continue he must change with the society that develops before him. Otherwise his appeal, based on his relevance to his readers, would reduce along with the profits of DC. Truly, Batman is the hero we deserve.

Now, say you all angrily bombard me with primary sources where Stan Lee talks about the illusion of change and that it applies to all DC and Marvel comics that have ever been and shall ever be. What then? Well, we must read such comics to consider whether we agree with him. And I, respectfully, do not. Sift through 75 years of Batman end-to-end and you will see that he has clearly changed. The Dark Knight of today is not the Caped Crusader of yesteryear. His storybook is massively varied, moving through whole lifetimes with alterations in personality, priority and result. Thus, there are numerous Batmen – the unrepentant killer of 1939, Robin’s fun big brother of the 1940s, the 1970s Detective, and so on. The reason for this links back to the arguments within the illusion theory: if Brand Batman is to continue he must change with the society that develops before him. Otherwise his appeal, based on his relevance to his readers, would reduce along with the profits of DC. Truly, Batman is the hero we deserve.

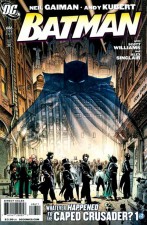

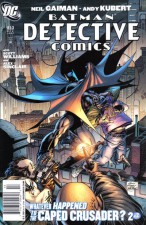

But one might argue that personality shifts do not adult character development make, however fundamental that change is. Taking each defined period of Batman he remains Batman – Bruce Wayne with his manor and his Alfred and his parents-who-are-deeeaaad! He has yet to decide that being a master of interpretive dance better suits the needs of Gotham. Nevertheless, DC has supported stories where the unexpected occurs for Batman and his associates in exactly the same ‘fan fiction’ spirit that Henry and Moonhead Press evoke. A good example of this is Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?, a two-part tale published in Batman and Detective Comics. In it, Neil Gaiman wrote a confessional for Alfred Pennyworth, revealing that the Wayne butler had in fact created the Joker to fulfil Bruce’s need for vigilantism. So, Moonhead Press is by no means the first to have imagined that the Joker is a mere fiction to justify the presence of Batman.

‘But that is not canon!’ – you cry. Ah, canon – that big bible of approved stories which make up the official first-life of our superheroes. It is the dogma we cling onto so we may pretend that certain events do not matter whilst ignoring, entirely, how the human brain works. For instance, what if something is so good that – though non-canonical – it becomes a seminal text? The Dark Knight Returns is apparently not canon, and yet Scott Snyder the current writer of Batman cites it as an influence. Does he forget this when he sits down to write? Hardly. Fans tell me that my research focus – the Batman of 1939 – also has no relevance because he isn’t canon either. My retort is that Frank Miller had this year in mind when he wrote Batman: Year One. This tells us that canon is something to be applied with caution; that our genre – the serial superhero comic book – is a metatextual device. Though Batman is a considerably conservative story it is nevertheless a clever one. No matter how many times we retcon a character, his rewound landscape contains a nod to the society and the writers who accessed his preceding ‘erased’ stories. Batman has changed, Batman does change, Batman will change.

Let us consider The Deal and how much change it offers. It is a blood-splattered testimony to the power of orgiastic violence and the feeling underneath the whole of Batman that there’s a fella who belongs in Arkham along with the rest of the lunatics. But these themes have been explored before within DC, albeit with less Alfred-in-boxes. The Bill Hicks quote it contains argues that the solution for Gotham’s ills is not a man dressed head-to-toe in Kevlar and rubber, but someone who will provide schools and healthcare. Bruce and Batman (like many members of Western society) exist in a nonsensical Victorian mentality which likes to believe that there is a ‘deserving poor’ which would never resort to crime no matter how loudly their stomachs rumble. Nevertheless, Bruce Wayne provides a large and effective welfare system in his city for this ‘deserving’ – or at least willing to change for the better – poor through the Wayne Foundation. So I would argue that the sentiments of this quote are very much evident in Batman’s mainstream publications.

The Deal does appear to offer one change, one which is the real reason why it could never, ever become a reality. Its central premise is one which accuses Batman of being the same monster he fights. This is wrong. Right from the very beginning – his chilling, unremorseful heart of 1939 – Batman made a point of telling us he ‘fights for righteousness’ and exists to ‘bring justice where none can be found.’ But much more than this – he defined himself as separate from his prey, for it is they who are ‘the cowardly and superstitious lot’. His costume, his manner, his myth plays on their fears, not ours. Batman’s particular vigilante schtick – an odd one, for sure – exists only to terrorise criminals. So, the notion of the Joker as his interchangeable soulmate within The Deal is not a challenge to the illusion of change but the creation of another entity altogether. The man in The Deal is not Batman, and so our Dark Knight – with his oddness and his rich resource of ideas for what makes someone heroic – remains untouched, unchanged.

Of course, this analysis is all very nice but isn’t the bigger question posed really: Why doesn’t Batman kill Joker? Well, there may be a clue to Batman’s apparent failing within the Golden Age. In his second appearance – The Joker Returns (1940) – the Harlequin of Hate suffers a fatal stab wound. His body is placed on a stretcher but on examination he is found to somehow be alive. And how ironic is that? All this time we’ve debated Batman’s lack of powers and never stopped to consider that we may be looking at the wrong man. The actual super(natural)man of Gotham could be the immortal Joker.

Of course, this analysis is all very nice but isn’t the bigger question posed really: Why doesn’t Batman kill Joker? Well, there may be a clue to Batman’s apparent failing within the Golden Age. In his second appearance – The Joker Returns (1940) – the Harlequin of Hate suffers a fatal stab wound. His body is placed on a stretcher but on examination he is found to somehow be alive. And how ironic is that? All this time we’ve debated Batman’s lack of powers and never stopped to consider that we may be looking at the wrong man. The actual super(natural)man of Gotham could be the immortal Joker.

[…] https://www.brokenfrontier.com/batman-the-real-deal/ […]

Good analyis there, Joe

[…] “Batfan,” Krawec writes both on her own blog and for Broken Frontier, and in her article “Batman: The Real Deal,” she makes the observation that “The Deal” explores the time-honored idea that Batman’s […]