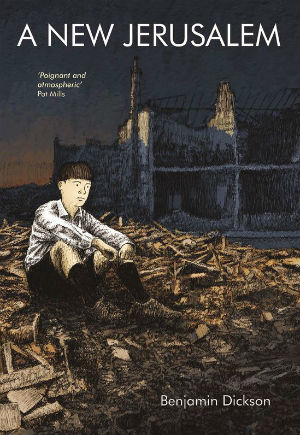

The further you get from an event, the more the specifics of what happened dissipate into hazy generalities. It’s on turning and looking back at the Second World War from that distance, through the wrong end of a telescope, that a global conflict fought (and suffered) by individuals becomes a battle between nation states. These traumatic incidents in human history are absorbed into a Grand Narrative, the chapter closed.Yet the causes and lingering effects of WWII cannot be tidily contained within the official period of hostilities. Benjamin Dickson’s A New Jerusalem begins in 1945, with eleven-year-old Ralph playing at being a Spitfire in the bombed-out ruins of suburban Bristol. He and his friends point sticks mimicking machine guns at one another. They share exaggerated fantasies of what their fathers are doing over in Europe. This imaginary world collides violently with reality upon the return of Ralph’s soldier father.

The further you get from an event, the more the specifics of what happened dissipate into hazy generalities. It’s on turning and looking back at the Second World War from that distance, through the wrong end of a telescope, that a global conflict fought (and suffered) by individuals becomes a battle between nation states. These traumatic incidents in human history are absorbed into a Grand Narrative, the chapter closed.Yet the causes and lingering effects of WWII cannot be tidily contained within the official period of hostilities. Benjamin Dickson’s A New Jerusalem begins in 1945, with eleven-year-old Ralph playing at being a Spitfire in the bombed-out ruins of suburban Bristol. He and his friends point sticks mimicking machine guns at one another. They share exaggerated fantasies of what their fathers are doing over in Europe. This imaginary world collides violently with reality upon the return of Ralph’s soldier father.

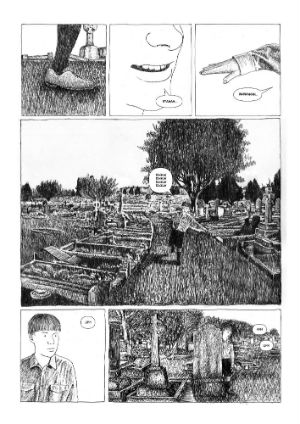

Dickson begins the book with the announcement of Germany’s unconditional surrender. This overture of historical record comes over detailed pencil drawings based on archival photographs; soldiers on beaches, naval ships returning home, and the Nazi death camps are all rendered with the photorealistc style of Brian Selznick. As A New Jerusalem turns the telescope the right way round, the faces become more recognisably cartoonish: pin dots for eyes and lines for mouth and eyebrows, not unlike the work Raymond Briggs. And similarly to Briggs’s Ethel and Ernest, Dickson does not directly adapt the precise incidents or life story of his parents for his war-time drama, but draws on his father’s post-war experiences in Merseyside. He’s also done his research about the specifics of PTSD, the effects of which rattle Ralph’s father.

His struggle to reintegrate into an atomised British society leads to his involvement in a resurgent labour movement, heavy drinking, and a volatile attempt to adapt to his dual roles of father and husband. Dickson welds recognisable elements of the coming-of-age narrative onto the specifics of post-war Britain. Ralph learns about sex from the impulsive, semi-public rutting of young lovers reunited by the cease in conflict; is bullied and subsequently stands up for himself against neighbours spreading gossip about his family; and has his mythic conception of his father challenged in a finale which (without spoiling too much) is at least halfway-Oedipal. It’s that final plot point that perhaps pushes A New Jerusalem from well-researched historical fiction to melodrama. Prior to that, it’s a vividly monochrome and emotionally-involving tale of the trauma wrought when the war is smuggled back home.

Benjamin Dickson (W/A) • New Internationalist £12.99/$19.95

Review by Tom Baker