John Allison’s work with in the Scary Go Round universe has been a long-standing high water mark of quality webcomics. Particularly after his shift in the late 2000s to a hand-drawn style; the warmth of his art then finally a match for the heart contained in his stories. The long arc of Allison’s artistic journey with the residents of Tackleford, though, creates an interesting case study given that in 2014 he decided to create a virtual remake of his pre-millennium Bobbins series. The collected version of those strips from 2016 provides commentary on Allison’s goals in re-examining and reshaping work he had done over a decade previously and poses deeper questions for any cartoonist who works in long-form fiction.

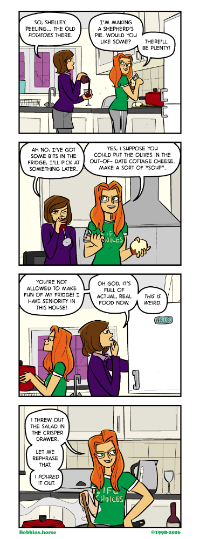

As Allison admits, his early work looks “rough beyond belief”, especially in comparison to the output of the confident cartoonist he has become. Yet in having his more recent work connected both in setting and characters to those early strips he can never truly be free of them. We see his long-running protagonist Shelly Winters speaking the first line of the first four-panel gag strip of the original Bobbins, creating a problem only a handful of other indie comic creators (mostly the Hernandez brothers) have had to tackle. How does a cartoonist continue to develop the world they have created yet reconcile that their early attempts to sketch out that world were done with far less clarity of vision and talent for rendering than they presently have?

As Allison admits, his early work looks “rough beyond belief”, especially in comparison to the output of the confident cartoonist he has become. Yet in having his more recent work connected both in setting and characters to those early strips he can never truly be free of them. We see his long-running protagonist Shelly Winters speaking the first line of the first four-panel gag strip of the original Bobbins, creating a problem only a handful of other indie comic creators (mostly the Hernandez brothers) have had to tackle. How does a cartoonist continue to develop the world they have created yet reconcile that their early attempts to sketch out that world were done with far less clarity of vision and talent for rendering than they presently have?

Here Allison choses not simply to redraw the older strips in his modern style, but instead to create story arcs that would have happened between the original strips. The effect being that the original mainline strips are superseded, though not wholly erased, by these new strips. They effectively swap places; the gag strips are then the moments in-between the longer story arcs. It’s an interesting solution. Allison honors his early attempts but puts them in their rightful place. Revisiting the characters and timeframe of Bobbins so many years later gives him a chance to draw out what he may have been seeking to express all those years ago. As he writes, “some of it was already there on those old pages.” But as he admits that when writing in his early twenties he, “didn’t know how to approach character’s internal lives and motivations”, now he is able to render and express that world both more sharply and with greater empathy.

The first collection houses three story arcs centered around a young Shelly Winters trying to make her way in the world post-university. The first concern her attempts to find an apartment after her parents decide to sell their family home. This one hews close to the series’ gag strip origins with Shelly going through a series of comical misfires until she fools her new housemate into believing she is not the least bit “loopy, scatty, erratic.” The second longer arc leans into Allison’s ability to create a longer sitcom-esque storyline where Shelly and company attempt to reverse the fortunes of the failing listings magazine they work for by introducing a Sex and the City-style column.

Shelly is ill-equipped to write this column and must call upon the head of the magazine’s teenage daughter (Scary Go Round regular Amy Pickering) to ghost write it for her. Misunderstandings and mishaps pile up as Shelly’s younger sister finds a rough draft of one of her columns and turns it into a class presentation, giving Allison a chance to write scenes for the headstrong grade school student and beleaguered parent archetypes he had been exploring in his Bad Machinery series.

The third arc, showcasing the writer Allison has evolved into, is a slow burn story of the night of Amy’s 18th birthday and the interaction of all the parties involved. We examine Rich’s pathetic crush on Amy, Tim’s conflicted big brother role in Amy’s life, everyone’s confusion at Shelly’s relationship with her hulking but good-hearted boyfriend Bruno. The whole interplay shows maturity and a good eye towards human behavior. A minor story beat of Tim and Amy getting snuck into the Peas + Beans factory for a late night hot meal captures that everyday magic that can sometimes creeps into our lives. The collection ends on a cliffhanger, though it appears Allison has revisited this part of his timeline in his online comics. Ideally there will one day exist a fully organized version of the entire story of the residents of Tackleford, which can sit comfortably next to the other magical realist histories of a town Allison seems to be drawing from.

A note must be made of the way in which Bobbins is drawn. Allison consciously chose to stick to the four-panel construction he had originally employed for the gag strip version. It is rarely a hindrance here and he effortlessly has one strip flow into the next during the more complex third arc. His characters are perfectly rendered in terms of communicating their performance. The panels are nicely composed, if at times he lets color do almost all of the work of setting the scene. But the brisk comedic strip pace rarely leaves room for moments to breath. This isn’t entirely a problem, but in the aforementioned late night diner scene, it feels as if there is room to be more cinematic; a chance to linger on such an interesting place and moment. Allison is certainly a talented enough cartoonist to handle such a moment, but perhaps the structures that he has imposed on himself or had subconsciously imposed on himself by the form of webcomics has limited his approach. Recent posts on Allison’s website hint at him wanting to move away from the constraints of the Tackleford universe. Just as the re-imaginrd Bobbins allowed him to give it new life it would be interesting to see what he could accomplish as an artist given a wholly fresh start.

John Allison is a cartoonist who needs little in the way of publicity. He has a substantial and strong body of work and he has developed a following commensurate to his talents. What makes this Bobbins collection so interesting is that we have reached a point where a cartoonist of the webcomics era has created work deserving of introspection and re-examination by both its creator and its readers. While couched in the disposable daily strip form, these stories of the lives of the residents of Tackleford have over time all become part of a larger whole that touches the heart of the human condition. The final version of this whole stands to be Allison’s life work. It is one he should be infinitely proud of and the medium is deeply enriched for it.

John Allison (W/A) • Self-published

Check out John Allison’s archived webcomics online here

Review by Robin Enrico