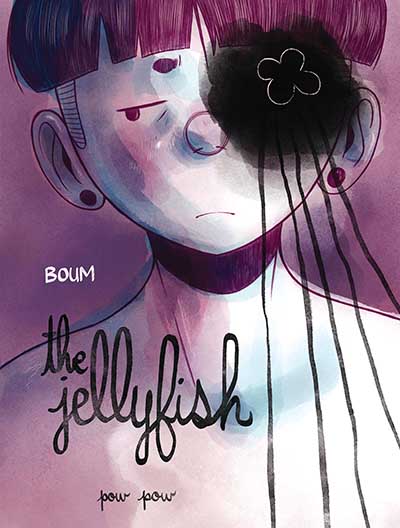

The cartoonist Boum (AKA Samantha Leriche-Gionet) has been a key member of the vibrant Montreal comics scene for over a decade. Her slice-of-life webcomic Boumeries, which with great savvy she self-published in both English and French, and the political fable A Small Revolution (Soaring Penguin Press, 2017) have already brought Boum’s work to the attention of readers far beyond her native Quebec. Now, the upcoming release of Boum’s award-winning, critically-acclaimed graphic novel The Jellyfish in English (out on May 7th from Pow Pow Press) is set to bring this prolific indie author’s work to an even wider audience. The Jellyfish, which author Kate Leth (Mall Goth) calls “one of the most beautiful graphic novels I’ve ever read” is Boum’s most accomplished creation to date, a visually-stunning work of fiction that draws deeply on Boum’s own experiences to create a funny, dark, and ultimately hopeful look at disability, desire, and the power of friendship.

In this wide-ranging conversation with fellow Montreal cartoonist François Vigneault, Boum dives into the creation of The Jellyfish, the various influences that can be seen in her art, the reasons she switched to working digitally for this book, and why after years of drawing autobio comics she decided to use a fictional lens to tackle “the most personal book I’ve ever made.”

François Vigneault: Your graphic novel The Jellyfish has already had a lot of success on the French side, it’s been nominated for a bunch of prizes and it’s won several awards. So, number one, how do you feel about it coming out in English?

Boum: It’s been unreal, the attention that it’s been getting in French. Not gonna lie, I hope it’s gonna get some attention in English as well! It’s nice to give it a second life. I’ve had English-speaking readers for a long time now. I’ve had a bunch of books published in French, but very few in English. So they’ve been looking forward to this book for a while. I have an English-language Patreon page where I’ve been posting work in progress of the book from the start, since 2019. They were there with me when I was working on a pitch for it, so they’ve been waiting for a long time for this. I’m excited to be able to get this book in their hands.

FV: Were there any challenges in translating the book from French into English?

Boum: It’s actually the first time I worked with translators. I speak English, and I had self-published books, and I would do the translation myself. I mean, it works, but working with translators means that The Jellyfish will have the best translation I’ve ever had. It was an interesting process to see how translators Robin Lang and Helge Dascher made my book their own in some way. Translating is not like doing a literal word-for-word translation of every speech balloon in the book. I was able to work with them, which I guess wouldn’t be the case with a language I don’t speak at all. So it was really, really cool to see the both of them at work, and then having a conversation with them. They would ask me questions: “Do you think she’d rather say this or that?” That was really interesting. I don’t know if it was a challenge, it’s like looking at my own work with a new set of eyes, like I didn’t write it. It feels so different. It’s great—probably better at some points! I feel like some scenes are tighter, and have more punch to them. I know other authors who’ve felt the same way; it doesn’t feel like it’s entirely yours anymore, but it’s a good thing.

FV: There’s an element of collaboration that comes into it with that, and it can kind of open up new windows, or new doors.

Boum: Yeah.

FV: This story is a very personal story in many ways. It’s a fictional narrative, but it’s based on some of your real-life experiences. Can you talk a little bit about that inspiration?

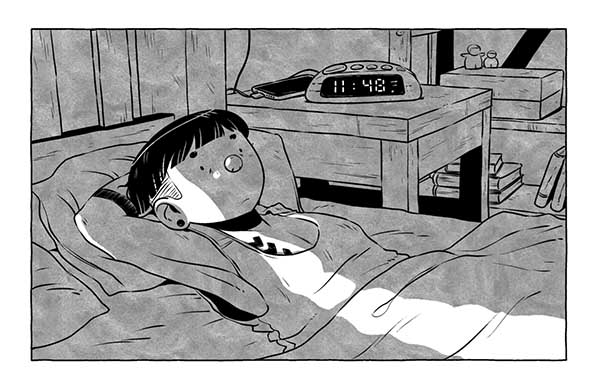

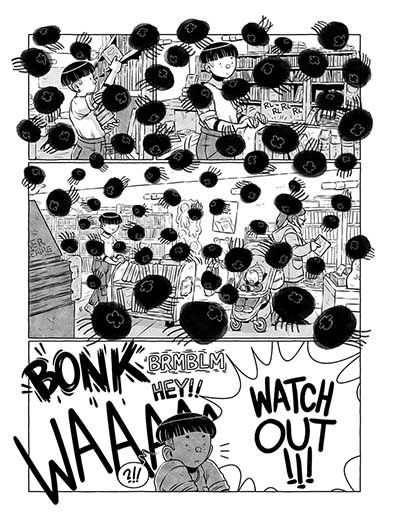

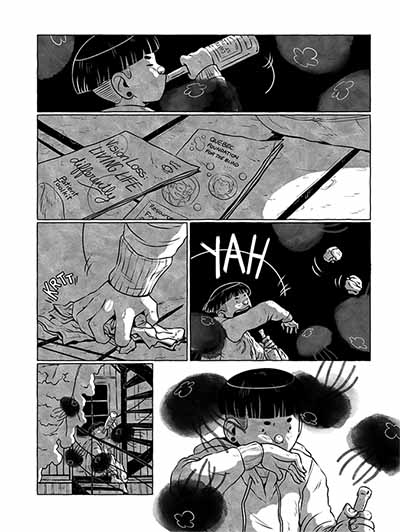

Boum: Basically the story wrote itself! In 2007 I started having eye problems. I would start to see a bunch of floaters—I think everyone ends up getting some at some point in their lives, like small dots in your vision, translucent gray dots. But I had thousands of them in the middle of my vision, and I didn’t get a diagnosis for it. I went to see an ophthalmologist for it, but they didn’t know what had happened. They figured I probably had some sort of inflammation that left scarring in my eye or something. The floaters are in the gelatin part of the eye, and they moved as a blob, and it looked like a jellyfish. It felt like I had the jellyfish in my eye at all times. It would be quite annoying sometimes, especially because whenever I would look at a really white surface, like a sheet of paper, I would try to draw something very detailed and the jellyfish would be in the way. So I would have to look away for a second, and then the blob would just move away for a second or two, and then I would draw the line before the jellyfish moved back into its spot in the middle of my vision. At some point I thought this would probably make for an interesting story, about a character with a literal jellyfish in their eye. And so I pitched it to the National Film Board of Canada, they had a contest for animated shorts. I pitched a five-minute animated short called “The Jellyfish” in 2010, and I was one of three finalists. So I did good, but I didn’t win.

I was sad, but it’s a good thing, because I put the project in a drawer and forgot about it for a while. But my eye condition kept worsening, and I was still interested in telling this story, and so I pulled it out of the drawer and I made it into a 200-page graphic novel, and the book’s much better than the film would have been.

FV: To tell the truth, I can imagine The Jellyfish having another life as a film.

Boum: I don’t think I would do it because, you know, I haven’t animated in 12 years or something! Frankly, I’ve moved on, I feel like I belong in comics now. Not that I didn’t like animation, but I found out with time that what I enjoyed was telling stories with drawings, and I think I like to have control of everything. I suppose that comics are easier in some way, for me, at least, with my busy family life, right?

FV: You mentioned there’s the visual metaphor of the jellyfish, which you develop throughout the course of the graphic novel. Without spoilers, I think we can say that things intensify as you go along. I was wondering as I was reading it, did you draw The Jellyfish digitally or analog?

Boum: I did the whole thing digitally. This is my 16th book, but it’s the first time that there’s no paper involved at all, which is kind of sad.

People will learn at the end of the book, or will know already, that I am partially blind. When I lost the use of my right eye, I found that drawing on paper was not as fun as it used to be, my perception of depth was altered because I had only one eye. When I draw on paper, it’s probably too close to my face, I draw really small on the paper. When I want to draw a line, it is never exactly where I think it will be, because I don’t see it the right way. And also drawing on paper gives me headaches, and I see double sometimes, because, you know, I’m blind in my right eye, but it’s not like 100-percent blind. Being blind is not like you just see black. I see some movement. I see some contrast. So it means that my eyes are competing against each other. So drawing on paper is kind of a pain.

I decided to use my iPad, which was a new thing that I had gotten in the year prior, and I had never really used it for more than just playing games or whatever. I got Procreate, which turned out to be a life-changing program. It’s a really good drawing application. And I thought “I could probably do the comic on this.” And so I penciled the whole thing on my iPad.

And for some reason, I think thanks to the zoom and the undos and so on, drawing digitally is not as problematic as it is on paper. I also use the computer, and because I have an old fashioned Wacom tablet, the distance is fine, the perception of depth is corrected somehow. I don’t have the same problem. So it’s just so much easier for me to draw digitally now.

I’m bummed out because I don’t have originals anymore. Not that I make a fortune selling them, but it’s always nice to look at other artists’ original work. I was in Angoulême this year, and you get to see how the masters would, you know, correct their mistakes, because no one’s perfect. It’s just nice to see the real things and I don’t have that anymore. I guess it’s the crutch that I need for my disability now.

FV: I totally understand, and at the same time, the book itself is the work of art in some ways, it moves it almost more towards literature than the visual arts in some ways, right? Like, it’s the whole story that you’re telling that becomes the creative output.

Boum: Well, hopefully. I think the book looks good!

FV: You’re not alone. I think it looks wonderful.

Boum: Thank you.

FV: The Jellyfish takes place over the course of the year, and I really like the sort of seasonal rhythm of the book. And your main character, Odette, they go through all kinds of emotions during that year, everything from desire to frustration, grief, denial, anger, and ultimately a sort of acceptance of their condition. Was it hard for you to put your character through the ringer?

Boum: Oh, yeah! I felt bad! I felt terrible at times. That’s what happens whenever I subject a character to something sad. Like in another one of my books, everybody dies! And I felt terrible, but sometimes it’s needed. With The Jellyfish, yeah, it was hard. It’s weird. It’s like this character becomes your child. I write in a certain way, I don’t know if it’s the same for everyone, but I create a character, and then I get to know them, and it’s like the character makes their own decisions. Sometimes, you would want the book to go a certain way, but then you feel like, no, the character wouldn’t make that decision, they would take another path. And it’s strange, because you’re the one writing it, ultimately you’re the one making the decisions. But it feels like sometimes the character, they lead the life they want to, or maybe they don’t want to. The character is kind of alive, and then you give them a disease or disabilities, and the character, they have to react in a certain way. They get angry, and they get sad, and I felt terrible, but it’s a good thing, you know? I feel like the main character learns and adapts and changes throughout the book, which is really important for me when I write. I feel like there has to be some sort of progress, the character shouldn’t be the same as they were in the beginning of the book. They have to be changed by the end.

FV: I think that’s certainly right. I think it’s actually refreshing in the book, because you allow your characters to kind of get into the depths of their emotions, even to the point of sometimes behaving in unlikeable ways. And it’s quite refreshing, because I think that there’s a tendency in literature and in some graphic novels to say “I’m going to demonstrate for you good behavior, and the right way to deal with something.” And in many ways, I feel like Odette and some of the other characters, you allow them to fail, like you said, so then they can pick themselves up afterwards, and I think it has more strength because of that.

Boum: Thanks, I do my best! Sometimes I don’t know what the hell I’m doing. But I feel like this worked out in the end.

FV: Now, one thing I noticed is there’s a couple of very specific manga references in the book. You talk about Battle Angel Alita, and you talk about one of my favorites, Ranma 1/2 by Ramiko Takahashi. I feel like I see a sort of a manga influence throughout the comic. Am I imagining things or is there something there?

Boum: I read manga as a teenager. It’s not that I don’t read manga anymore, because I just read some, but I don’t read a lot of it, and I’m really outdated—which I guess shows in the book, because I only talk about manga from the 80s and 90s! Back when I would read manga on a more regular basis, it was really, really hard to find. Like I would have to go to Chinatown to find it. Now manga is everywhere and it’s much easier to find. I would draw manga too, when I was a teenager. I think most people end up trying out a “manga” style at some point in their lives. But I don’t know that The Jellyfish is influenced by manga, but probably visually.

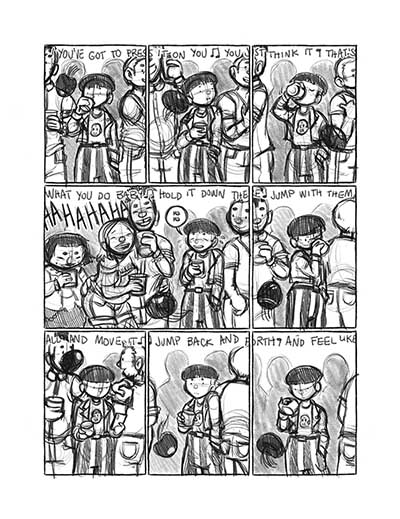

Also, I’m a gamer. I play video games. And my favorite types are Japanese role-playing games, and a bunch of them are anime or manga style. I feel like that’s probably influenced me more than the comics themselves.

But I’ve read and have been influenced by other comics that were probably influenced by manga as well. So it’s just a big mashup of things I liked and incorporated into my style. I don’t dislike being compared to manga. I think what I think the most obvious thing is probably how I make the compositions on my pages. I like to have really varied panel sizes and sometimes the panel’s going to go into the bleed and out of bounds. I like that kind of thing. And that’s a very manga thing to do. I don’t know. It’s a hybrid, but it’s fine. I enjoy being compared to manga. I got that feeling when I got the printed book for the first time. When I was working on it, I didn’t think it looked like a manga. And then when I got the book itself, with the gray shading and the bleeds and everything, I looked at it and it looked so alien somehow because I had never seen it in print. And I felt like I opened it and was like, “Whoa, it looks like a manga!”

FV: Yeah, I absolutely see what you’re talking about with the form factor. I think a lot of the Pow Pow books have that, it’s kind of a chunky little book, really dense, it’s over 200 pages. There’s the stylistic things, and there’s also some little things with the rhythm of the story. One thing I noted, because I was recently doing some writing about another manga, I noticed that you put a lot of emphasis on objects, and the world that Odette lives in. Their pet bunny rabbit, Napoleon, the food, all the little objects and everything that’s lying around the apartment. It all feels very lived-in and real.

Boum: I hadn’t noticed that, but the food makes sense too. Like in anime, the food always looks delicious, the artists always put in that extra time so that everything looks mouthwatering, that kind of thing. I wanted that effect too. There’s a few scenes where there’s food involved in my book, I really spent that extra time making, like, the sauce very shiny. And so, yeah, it makes sense. I’ve probably been influenced and I don’t know it!

FV: Well, speaking of setting, this book is very much set in Montreal, in the city that you not only live in, but you were born there too, right?

Boum: Yeah. I haven’t moved. I mean, I have moved around, but always within Montreal. I’m a city person.

FV: It’s such a great city. I mean, why move?

Boum: Yeah.

FV: Do you feel like that the city has had an influence on you and your art? Be it from the culture of the city, or the comic book scene, or anything like that?

Boum: The comic book scene certainly helps, I guess. There’s a really, really great community here. Everyone is so close by, there’s a bunch of cartoonists that live in the same neighborhood. I’m just like, a tiny bit further away from there, but it’s not that big of a hassle to go and see them.

What I like about the Montreal comic scene also is that it’s bilingual. We’ve all had multiple influences, and then we’re all together in the same city, and we make comics together. I just think it’s awesome.

I don’t know if the city of Montreal itself influenced my work. I decided to set the story in Montreal just because that’s what I know, of course. I put Odette and their friends in a bunch of places that I go to and where I’ve been. Odette’s apartment is my first apartment. I remembered how it was, the layout of it. I don’t live there anymore, obviously, It’s been years and years. I went to take a bunch of photos… I don’t know if the current tenants saw me cause I was there often, and I would even go on their balcony. I didn’t take pictures of the inside, cause I knew what it looked like, but I needed some reference of the surroundings. I felt kind of creepy doing that! I don’t know if they were like, “Oh, here’s that freak again with her camera!” Anyway, Odette goes to the store where I would do my groceries when I was like 20. It’s interesting that I was able to immortalize this part of my life with a fictional character.

FV: That brings up another thing I was thinking about, which is that you did a comic strip called Boumeries, which people can find online, you translated it yourself into English so people can read it. And you did that for what? 10 years?

Boum: Nine. I self-published ten volumes, but it’s nine years, officially, yeah.

FV: Nearly a decade. So you had worked in that autobio realm. Was there something specific about this story, that you were inspired to do something fictional rather than autobiographical?

Boum: I guess because I’ve done so much autobiography, I wanted to do something else. That’s interesting though, because when I signed with Pow Pow, at the beginning Luc [Bossé, editor of Pow Pow] asked me, “Why don’t you go autobio with this story? Because obviously it’s inspired from what you’ve been going through.” And I was like, I’ve just had enough. I want to move on. And also my avatar, the way I draw myself, is really associated with humor. I felt like drawing something more serious. I feel like my story, the real story behind having eye diseases and losing an eye, was kind of boring! I would go to the hospital, and get a diagnosis or treatment, and then I would go back home and cook dinner for the kids. Because I’d had so many problems for so long, it didn’t come as much of a shock when I lost my eye. I kind of knew this would happen at some point, I had been walking on the street and covering up my eye, and being like, “It’s not so bad, I can live with this.” So when it happened, I didn’t cry. I was kind of annoyed that I would have to go back to the hospital. So I didn’t feel like it would have been as interesting to read. And so I decided to make a fiction out of it.

Which I find interesting, because I’ve done journal comics for nine years, but I feel like The Jellyfish is the most personal book I’ve ever made. Just because it goes more in depth into emotions, and fears, and that kind of thing. It felt liberating to be able to take my problems, give them to a fictional character, and then do whatever I wanted with it. Like, it’s not my story. I’ve made stuff up. I feel the book is better that way.

FV: I can totally see it, because the fictional narrative can function as a lens, to take a little bit of an optical turn, and it can help focus in on all the key things that you really want to get across. So I can understand why this would be such a personal book. I know I definitely was very affected by it—It’s a very beautiful and touching story, and it’s quite meaningful, I think, to any reader at any stage in their life. When someone finishes the book and they close the last page, what would you hope that they take away from The Jellyfish?

Boum: That’s a good question, and a hard question. This whole idea started when I realized that my now-husband would forget that I had eye problems. He would randomly ask like, “Hey, do you still have your jellyfish?” And I’d be like, “Oh yeah, you don’t have to think about it all the time, like I do.” So I wanted the readers to know what it feels like to have something in your face all the time. You can’t not think about it.

It’s a highly personal tale, but it works with just about any chronic disease. It doesn’t have to be about a loss of eyesight, it could be about anything. Some people told me it felt like depression, some people felt seen with their own chronic diabetes. People will relate if they have something in their life that’s like that, either their own story, or a family member’s. So I feel like, people who don’t have any kind of chronic disease should close the book and realize that some people have a lot more going on behind the scenes than you would think. Invisible disabilities and invisible diseases exist, and you don’t know what this or that person is going through, and what they have to live with in their everyday life.

I think it’s also important, the message of the book is also that our chosen family is really important, the people you want to be with and the people who will support you through hardships. That’s what I want the reader to be left with when they finish the book.

FV: What a wonderful, empathetic note to end our little talk on. Thank you so much for taking some time to chat with me. I’m really excited about this book coming out in English, I thought it was wonderful.

Boum: Thank you.

Photo © Prune Paycha

The Jellyfish will be in stores on May 7th 2024.

Interview by François Vigneault

[…] available in Fr & En both from Pow Pow. Which was inspired by her experience of losing the sight in her right eye the year before! This isn’t new but was just noting her accomplishments […]