When 2000AD announced on Tuesday morning that ‘art droid’ Brett Ewins had died the previous day, aged 59, there was an outpouring of shock and sadness across social media, from readers and fellow professionals alike.

So why, after almost a quarter of a century of withdrawal from the ‘industry’, did Brett Ewins continue to mean so much to comic readers?

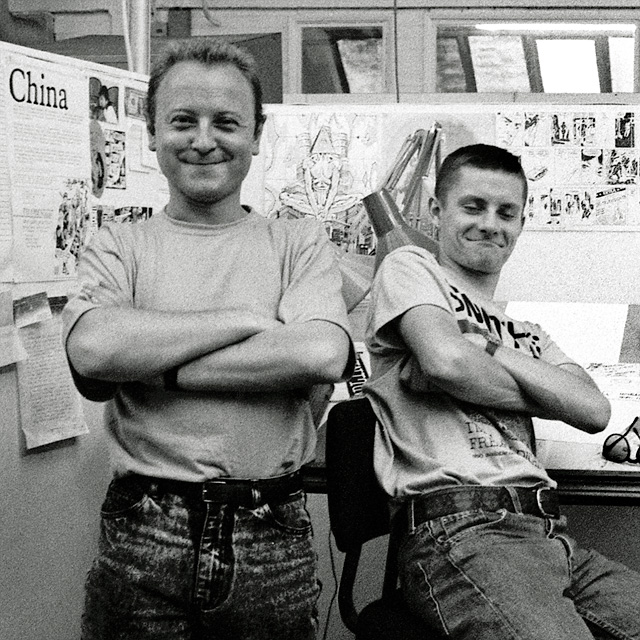

Brett Ewins with Jamie Hewlett in the Deadline office, 1988 (© Steven Cook/National Portrait Gallery)

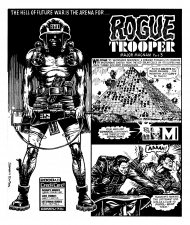

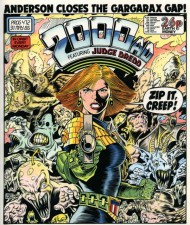

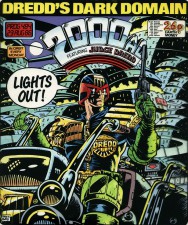

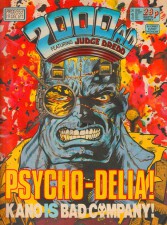

First and foremost, he was a stylist. The work with which he’ll mostly be associated was in the early days of 2000AD, and in a heavyweight division that included Bolland, McMahon and Ezquerra, Ewins could trade inky punches with the best of them. From the grotesque decadence of his Judge Cal to the sleek lines of Judge Anderson and the visceral horrors of Bad Company, his work was instantly recognisable.

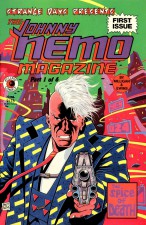

He also brought a sharp design sense to his comics. He left his mark on the look of Dredd, while the exquisitely tailored nihilism of Johnny Nemo and – later – Veto Skreemer also bore his unmistakable imprint. Twenty years ago I even bought a pair of enormous blue shoes from Shellys purely because they looked like something Brett Ewins would give one of his characters.

And while the term is bandied around a little too easily, Bad Company’s Kano will forever remain one of the most iconic embodiments of 2000AD’s “bastard with a big gun” archetype. Meanwhile, Ewins’ futuristic cityscapes, including Mega-City One and New London, were also an intricate joy to behold.

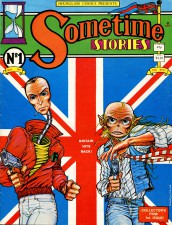

However, with the founding of Deadline in 1988, with co-editor Steve Dillon, Ewins moved from comics practitioner to facilitator. In the age when Paul Gravett and Peter Stanbury’s Escape already sat on newsagents’ shelves next to i-D and Blitz, there seemed nothing more natural than an energetic monthly mix of comics, pop culture and style.

Propelling the careers of talents including Jamie Hewlett, Philip Bond, Nick Abadzis, D’Israeli and Glyn Dillon, Deadline became so influential that by the mid-90s (though no fault of its originators) it was almost impossible to read or write a small press comic review without the term ‘Deadline-esque’ turning up.

By that stage, unfortunately, the pressures of work had taken their toll on Ewins’ physical and mental health. After a breakdown in 1991 he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, and he largely withdrew from commercial work. However, while his conditions prevented him from taking on comics projects, his restless creativity moved its focus onto painting.

Characteristically, after his free-flowing work with Milligan and McCarthy on Strange Days and the open-access gang mentality of Deadline, he soon found another ‘family’ of collaborators in the IFC (InsaneFelonsCartel) street art crew and the legendary Mutoid Waste Company.

Sadly, Brett Ewins came back to public attention in January 2012, when his world crashed down around him. Concerned about the noises coming from Brett’s house, neighbours called the police. In the subsequent altercation, a police officer received a knife wound to the hand and Ewins ended up in a coma after receiving a heavy blow to the head and suffering cardiac arrest.

His old friend Tony Wright (aka Tony Riot) has related Brett’s initial incarceration and subsequent trial with admirable thoroughness and objectivity. It’s a harrowing, almost nightmarish narrative of how society can fail its most vulnerable members and how the criminal justice system can chew them up.

That things ended as ‘positively’ as they did, with Brett having his charges downgraded and being released after nine months in hospital and on remand, is as much as anything a tribute to his local MP, Steve Pound, a long-time friend and comics fan who visited him during his incarceration and acted as an advocate when he was denied his vital psychiatric medication.

I was lucky enough to meet Brett once. It was in September 2013, around a year after his release, when Gosh Comics was hosting a launch party for the Best of Milligan and McCarthy collection from Dark Horse. Brett was in attendance, and the two principals were keen throughout to stress his contribution to their creative partnership.

Afterwards, I overcame my usually debilitating shyness to go and tell Brett how pleased I was to see him and how much I’d enjoyed his work over the previous 20-odd years. He looked dapper, as tanned as a London summer would allow and fairly relaxed (even though it was his first venture into the city centre since his ordeal). Grateful and gracious, he spoke positively about the future and the novel he was working on, to be published by former 2000AD editor Alan McKenzie.

That’s the stylish and creative Brett Ewins I’ll remember every time I revisit his stunning but tragically abbreviated body of work.

[…] with mental illness. London-based journalist Tom Murphy praised Ewins’ sharp sense of design in a moving tribute: “He left his mark on the look of Dredd, while the exquisitely tailored nihilism of Johnny […]

Growing up I had a signed print of Brett’s Anderson cover hanging on my bedroom wall, I loved his work. It is so sad to read what happened to him, I had no idea.

[…] middle-class comprehensive school childhood. I went to the same secondary school as cartoonist Brett Ewins (RIP), although he was there some years before me. I often used to see him walking past the school, […]