Our Inside Look feature at Broken Frontier provides creators with the opportunity to share exclusive commentaries on their comics projects with our readers, giving insights into the genesis, process and themes of their work. Today UK small presser Daniel Bristow-Bailey discusses his experimental graphic medicine offering The Screaming, recently reviewed here at Broken Frontier.

Back in the summer of 2019 I was off work for a long time with depression and taking all sorts of different prescription drugs to try and find something that stabilised my mood a bit without too many nasty side effects. The upside of this was I had an awful lot of free time in which to make comics.

Before The Screaming, I’d approached the subject of mental health and medication in the shorts ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Soup of Conflicting Neurotransmitters’ (published in You are not Alone, Ed. Abby Kacen, 2019) and ‘Medication Review’; (published in Feral Comics #4, Los Angeles, April 2020).

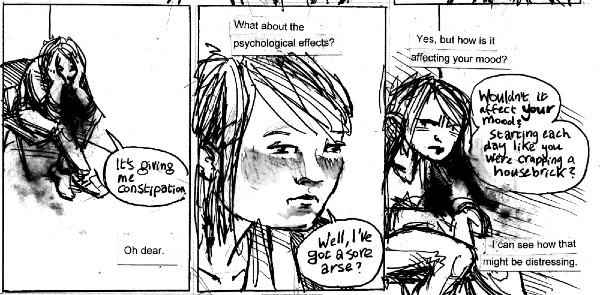

In ‘Medication Review’ (above) a woman has a conversation with her psychiatrist about her drug regime making her constipated. In early drafts of the strip, the protagonist was a man, but I found flipping the gender elevated the script from a string of bottom jokes into something more unsettling – we’re socialised into laughing at/along with men making scatalogical jokes but feel less comfortable when it’s a woman doing the talking.

The other advantage of having a female protagonist, both in this short and The Screaming, is that it makes it explicit that these are fictional works rather than diary entries – they may be autobiographical in theme but I never like feeling constrained by a duty to stick to “what really happened”.

In ‘Medication Review’ I also kept the psychiatrist invisible, presenting his (in my head he was definitely a man) speech as narration boxes. I liked the way this created a sense of disconnection between the patient and doctor, as though he wasn’t completely present or engaged. When I started to write The Screaming, it occurred to me that, if I had the protagonist talking on the phone, I could make the doctor’s side of the conversation invisible and inaudible, heightening the sense of disconnection further. It’s always great as an artist when you realise you can make a piece work better by leaving something out.

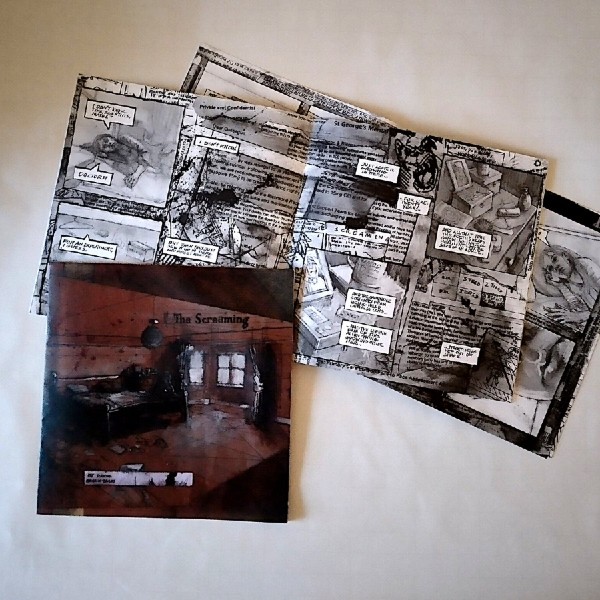

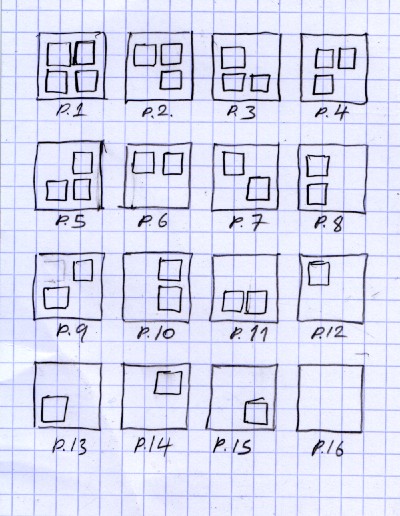

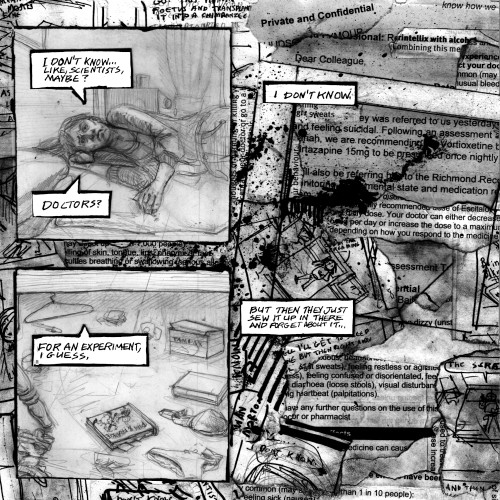

The other idea that had been floating around my sketchbooks for a while was using a rigid grid and working my way through all the page layouts possible within a set of constraints – here working to a 2×2 grid, where each space on the grid can either be occupied by a panel or not, giving a total of sixteen possible layouts; sixteen pages also, fortuitously, being a good length for a short comic (I did briefly consider doing the same thing with a 3×3 grid, but you’d need 512 pages for that. A future project, perhaps?) By using the panels for the “real world” and the rest of the page (margins, gutters and unoccupied space) for the dream, I hoped to create a sense of the dream surrounding, intruding upon, and eventually engulfing the reality – as you go through the comic, the number of “real world” panels gradually decreases as the dream narrative comes to the fore.

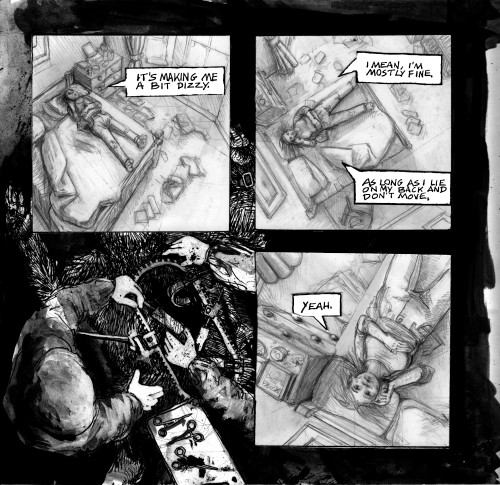

Having a whole comic about someone talking on the phone risks being very boring to look at. Rather than fight this, I decided to embrace the boredom and have as little movement or change between panels as possible. No-one said comics have to be fun, right? So here we have a sequence of thirty-two panels of a woman lying in bed, talking on the phone, meticulously rendered in pencil. With so little happening, the details of the mise-en-scene become very important – I had to draw a map of the room, and a separate one just of the clutter on top of the chest of drawers, to keep everything straight.

Aside from the horrible dreams, the other side-effect the protagonist is experiencing is dizziness – I tried to depict this by having the “camera” in constant motion from one panel to the next, always focussed on the protagonist, but doing so from increasingly weird angles.

The other way I differentiated between the two narrative threads was the choice of medium – I rendered the “real world” panels in pencil, trying to evoke a soft, indirect light like indoor daylight on a cloudy day. I think I was only partly successful in this but if you look at the paintings of Vilhelm Hammershøi you can see what I was aiming at.

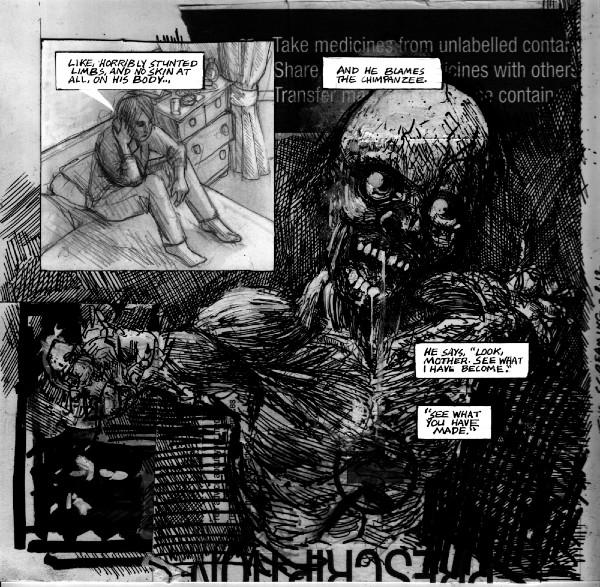

By contrast, I rendered the dream sequences in ink, going for stark black and white with lots of noise and spatter, turning the contrast on these bits right up when I was preparing the artwork for print. I also used collage – I wanted to use bits and pieces from everyday life to make up the texture of the dream, much as dreams are constructed from recycled fragments of memory.

The collage materials were for the most part provided by the good old NHS – a mixture of letters from mental health people, forms they wanted me to fill in, and those leaflets you get inside medicine boxes listing all the side effects. Aside from the two main narrative threads you can almost piece together a third story from the bits of paper I had lying around my desk.

The dream portion of The Screaming is a reasonably faithful rendition of a dream I had around this time. Before I wrote the comic, I started drawing images from the dream in my sketchbook just because they wouldn’t leave my head – the symbolic parallels between the dream and the protagonist’s situation only emerged later. I’m a big believer in allowing the subconscious to take a leading role in the creative process – often what seems like random weird nonsense turns out to have deeper resonances in retrospect.

As a formal experiment, I’d say that The Screaming was a success, and points the way towards longer-form work that I’ll attempt in the future. As a piece of personal history, it’s something I’m glad to have put behind me.

For more on the work of Daniel Bristow-Bailey follow him on Twitter here and Instagram here. You can find his online store here.

Feature by Daniel Bristow-Bailey

[…] The last thing I self-published was “The Screaming”, an experimental one-shot comic about dreams and mental health. I wrote about it in some detail for Broken Frontier. […]