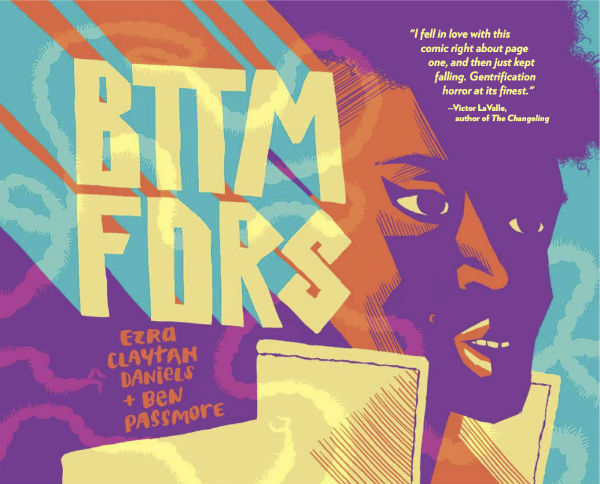

BTTM FDRS by Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore is not only an artistic highpoint for both its creators; it is a stunning reminder of the power of comics to explode the reader’s imagination. Daniels and Passmore both establish the mash-up genre of Splat-stick Gentrification Horror Comedy and create a work that utterly defines it. In Passmore, Daniels finds an artist who can bring velocity and humanity to his mind-bending science fiction. In Daniels, Passmore finds a writer who gives precision focus to his frantic cartooning and break-neck storytelling; with both of their cutting social satires coalescing into a single brilliant send-up of the complex racial and economic politics of living in a gentrifying neighborhood.

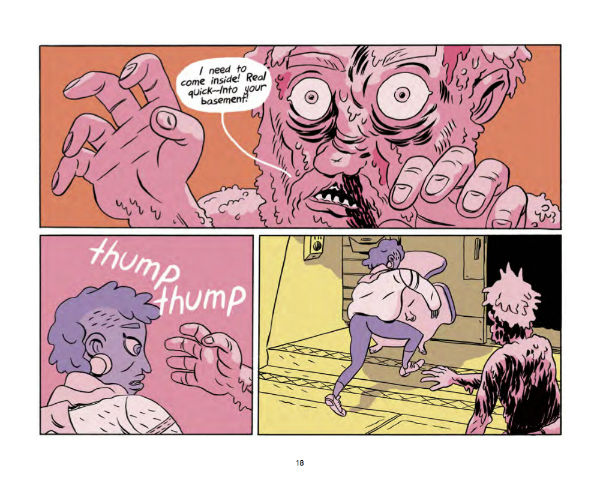

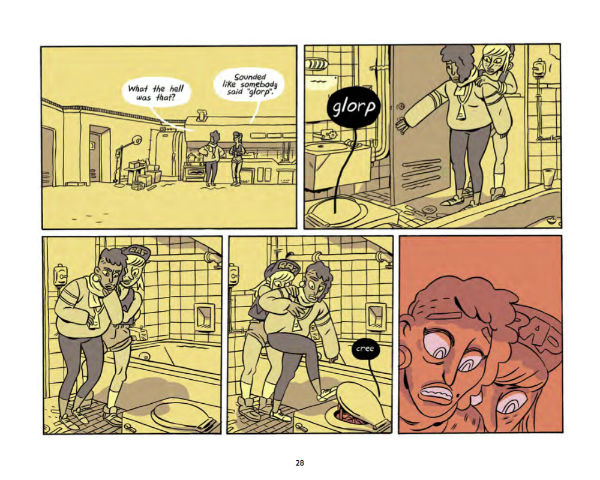

The book exhibits a winking genre savviness by planting seeds of dread in an early sequence that feels pulled out of the VHS horror era. Dwarfed by an enormous concrete slab of a building colloquially known as Moreau’s Castle, two city workmen try to get to the bottom of a power meter than never registers any usage. When one of the workers squeezes into a vent to investigate only to barely escape bruised, burned, and broken by what he saw inside the reader waits with bated breath for the other shoe to drop. And it doesn’t take long for that horror to bubble to the surface for Darla the building’s newest tenant and the story’s protagonist; as before she can even unpack she finds something that resembles putrescent intestines glorping out of her toilet.

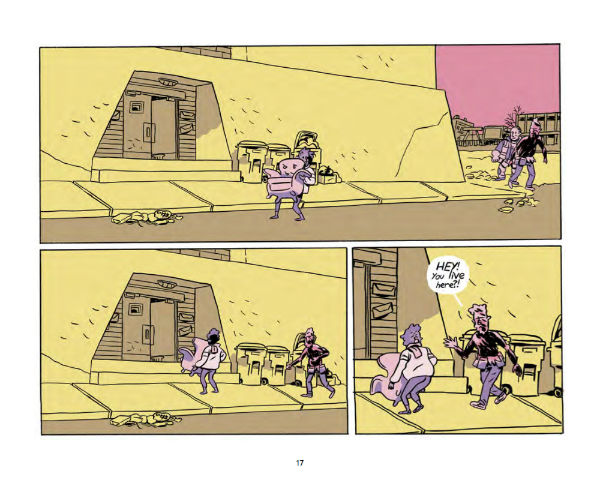

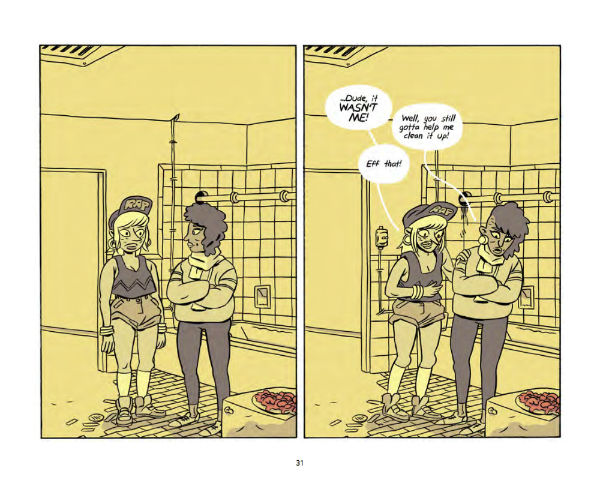

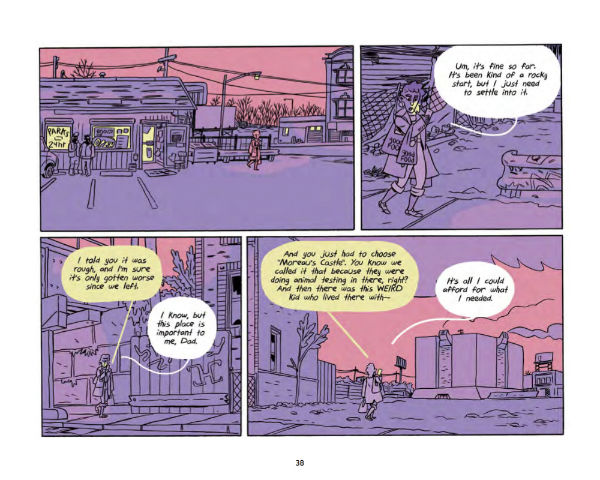

What brilliantly sets the tone of these opening sequences is the way that Passmore’s art allows the story to openly truck in horror tropes without feeling cliché. The reader has seen this type of story play out before, but never rendered in this way. Panels are frequently framed at a wide angle that emphasizes the emptiness and desolation in and around the building. In combination with the purposely-contrasting pastel neon color palette that separates the characters out from the background these compositions result in large areas of the page being filled with unearthly hues. Everything is a color out of space as the hallways are flooded with turquoise, Darla’s stark apartment is lit with lemon hues, and the sky outside is a soft shade of magenta. Though the mise-en-scène crackles with unease, the performance of Passmore’s characters by contrast loaded with comedy. Darla’s exasperated chemistry with her self-centered best friend Cynthia is played entirely for laughs. The terror oozing out of the pipes has the two teasing and tormenting each other like children and Cynthia ditching Darla for a hot date rather than staying to help her confront the first night in her strange new apartment.

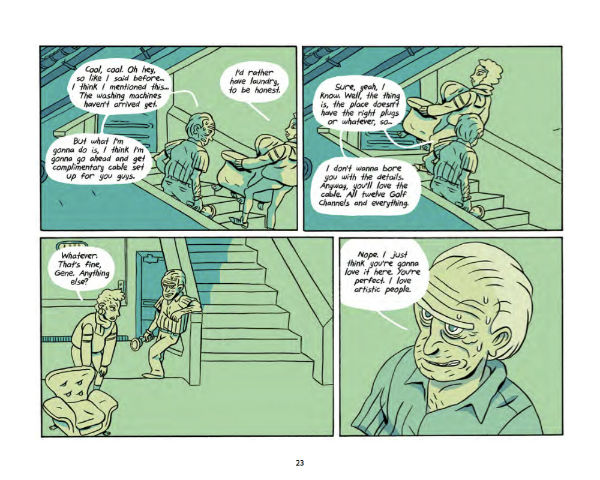

This subversion of horror standards continues into the complex politics surrounding the characters. Darla is hardly the stereotypical frightened protagonist but in a nuanced move she is also not playing the role of the innocent outsider treading into the unknown. Darla’s status as suburban gentrifier is complicated by the fact that her family moved out of the neighborhood when she was young, and now post-art school she has returned. Her class guilt is somewhat assuaged by the building’s long-term tenant Katherine who, even while explaining that she has been priced out of living there, assures Darla that everything that is happening is just part of an inevitable cycle of the haves taking from the have-nots. But as with the supernatural elements at play, Darla is unable to shake the feeling that beneath the surface something is very wrong with her moving into Moreau’s Castle.

These personal and political tensions explode before the ectoplasmic ones due to Darla feeling like her residence in the Bottomyards is being exploited for cultural cache. She notices when Cynthia becomes far more interested in the building after realizing Darla’s neighbor Julio is actually pilgrim themed rapper Plymouth Rock. Her feelings of being used for vicarious street cred are then further compounded when Cynthia name-drops both the neighborhood and her neighbor during a meeting with a fashion mogul. The resulting fight between the best friends coupled with a hostile encounter with the now deranged city workman from the beginning of the book leads Darla to seek solace from Julio as a fellow Bottomyards resident. While the two squabble at the bar over the problematic nature of their common in-between status as gentrifiers of color, they unite over their shared distrust of white people.

It is a highly confident move on Daniels and Passmore’s part to take this diversion into the racial and economic politics of Darla’s new apartment. The more personal nightmare of scummy landlords and being Common People-ed by your friends almost makes the reader forget the briefly glimpsed grotesquerie in the toilet. What really gets the reader invested is Daniels’ pitch perfect dialogue paired with the way Passmore’s cartooning nails the emotional performance at such a high level. That the reader even feel a little bit of sympathy for the crying Cynthia after she rightfully gets told off by her best friend is indicative of how well both creators talents are functioning in sync. Yet because BTTM FDRS is less a horror story of gentrification and more a gentrification horror story it doesn’t take long for Cynthia to ruin the neighborhood. As while Darla is off with Julio, Cynthia discovers a secret control room in the building and things quickly take a turn towards Giger-eqsue body horror.

The story’s two-thirds turn towards end-of-Akira tubular pulsating nightmare fuel splat stick comedy is masterfully handled by Passmore’s art. All of the staid silent emptiness and creeping dread of the earlier part of the book explodes in moments of kinetic brutal violence. The way in which he renders how the mind-shattering terrors from beyond that infest the building loll and undulate feels both real and stomach-churning. While the late story reveals of the origins of these horrors that slime and squiggle their way through the building is feels both wholly original while tonally in line with the social critiques Daniels has been making through out. With the book’s surprising conclusion bridging eldritch monstrosity and sad earnest emotionality together in an ending that burrows under the reader’s skin.

BTTM FDRS is a graphic novel that reminds us that even indie comics is a medium not a genre. By merging the commercial appeal of gruesome pulp with overt political discourse of the ‘zine scene it manages to capture the unnameable terror of our times. Though the plot and its characters feels in tune with other Social Thrillers of the moment, Daniels and Passmore use the medium to formalistically explode the genre. By trading close camera angles filled with darkness for neon colored wide shots they makes horror feel vital again. In revealing in the sweaty high-energy performance of the characters we can easily transpose our own anxieties about trying to survive city life with theirs. By going big with their sci-fi abominations, Daniels and Passmore remind us that comics have the power to take the unimaginable and the un-filmable and render them in bubbling roiling flesh right before our eyes.

Ezra Claytan Daniels (W) and Ben Passmore (A) • Fantagraphics Books, $24.99

Review by Robin Enrico