In Bumperhead, Gilbert Hernandez returns to his hometown of Oxnard for a bildungsroman of music and adolescence in the 1970s – given his own stylistic spin.

It can be a tough gig being an aficionado of the indefatigable Gilbert Hernandez: it seems that every couple of months you have to sit down, chew the end of your pencil and come up with a new configuration of superlatives to hail his latest book.

It can be a tough gig being an aficionado of the indefatigable Gilbert Hernandez: it seems that every couple of months you have to sit down, chew the end of your pencil and come up with a new configuration of superlatives to hail his latest book.

At least with a couple of his recent books – Maria M and Fatima: The Blood Spinners – I’ve been able to eke out a bit of a reservation about his more OTT genre work.

However, this time round, Bumperhead lands right in the sweet spot of what Beto does best: nestling into a little gap left between Julio’s Day and Marble Season, it focuses on the importance of childhood and adolescent minutiae, while also depicting the alarmingly swift passage of time and the shifting perspectives of age.

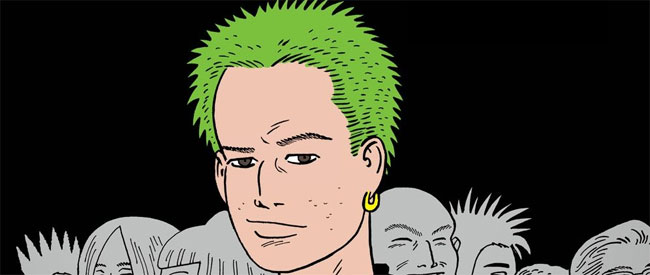

The book focuses on the early life of Bobby – cruelly labelled “Bumperhead” by the local kids, on account of his apparently outsized bonce – as he grows up and settles down in a fictional version of Los Bros’ Californian hometown, Oxnard.

The work is divided into five discrete parts set at different stages of his life, seemingly spanning the period from the cusp of the 1970s to some time around the present day or near future. However, the bulk of the book follows Bobby through the mostly low-key drama of a 70s upbringing in blue-collar America: serial relationships, parental problems, drugs, a dead-end job and music.

The work is divided into five discrete parts set at different stages of his life, seemingly spanning the period from the cusp of the 1970s to some time around the present day or near future. However, the bulk of the book follows Bobby through the mostly low-key drama of a 70s upbringing in blue-collar America: serial relationships, parental problems, drugs, a dead-end job and music.

One of the things that Bumperhead captures superbly – mostly through the surrounding characters who orbit the largely stationary Bobby – is the weird little trajectories people go through at that time of their life, when a random encounter or overhearing a particular record for the first time could send you spinning into a while new orbit.

Indeed, music soon takes its place at the heart of Bobby’s life, in the way it can at that age, totally defining your ‘tribe’ and your outlook. After throwing himself into the glam rock of Bolan and Bowie, Bobby later undergoes something of a death and resurrection, being brought back to adrenaline-pumping life – almost literally – by the power of punk.

However, among all the supporting cast, Bobby’s defining relationship is with his immigrant father. (His distracted, chain-smoking mother becomes more powerful as an absence than a presence as the book progresses.)

Early on, we see the little boy try to protect his father from casual racism and teach him the rudiments of English. However, it gradually becomes apparent that the older man is content to live a withdrawn life – something that becomes more overt when he suddenly ups sticks to return to Mexico, leaving the teenage Bobby (who has now left school and is working as a cleaner) to his own devices.

The book is narrated throughout by Bobby’s first-person, present-tense commentary, which gives the scenes a degree of dramatic immediacy; we live Bobby’s experiences alongside him, without the 20:20 vision of hindsight. Early on we get a sense of his romantic streak, though his overwrought poetic feelings for a local girl, Lorena Madrid. However, as Bobby ages, there’s a lack of affect about his narration that has a shocking pay-off at the book’s climax.

The book is narrated throughout by Bobby’s first-person, present-tense commentary, which gives the scenes a degree of dramatic immediacy; we live Bobby’s experiences alongside him, without the 20:20 vision of hindsight. Early on we get a sense of his romantic streak, though his overwrought poetic feelings for a local girl, Lorena Madrid. However, as Bobby ages, there’s a lack of affect about his narration that has a shocking pay-off at the book’s climax.

The final part of the book, in which Bobby has drifted into balding, unsteady middle age, is a potent little coda to the ‘main’ drama. By this stage, his relationship with his dad has been reduced to a series of repeated questions with forgotten answers. And when he meets his old acquaintances, he feels nothing towards them, just smiling and pretending to listen.

In the closing words of the book, Bobby declares that, “It’s been a good life. I really can’t remember what I was so angry about.”

However, in a powerful irony of the sort that comics do so well (especially in the hands of a master like Gilbert Hernandez), we can see that his apparent serenity is actually an anaesthetised disconnection. Bobby’s calm should be a thing of comfort, but as he disappears into the thick fog of age, it just highlights what he’s lost.

The legendary British DJ John Peel famously said of the enduring, idiosyncratic band The Fall that they were “always different, always the same”. And while Beto might not go off on quite as many perverse tangents as Mark E Smith, it’s a description that could be applied just as validly to his work.

Beto’s style has become so familiar and distinctive that at first glance, this collection of cartoony kids messing around in the ‘hood looks like the artist just doing his thing, as he has from the very first pages of Heartbreak Soup in 1983 to Marble Season in 2013. However, the measure of his genius is that he always manages to instil his work with something new and astonishing – even if not every touch of the unexpected hits the mark.

For example, the one element that threatened to throw me out of Bumperhead was a deliberate technological anachronism that represents a bold creative choice – generating the ability to look into the future – but also sows seeds of confusion in a book that relies so heavily on the evocation of a very specific period.

There’s also seems to be a bit of trans-temporal jiggery-pokery in the final section that isn’t clear and seems a little out of place in a work that otherwise benefits from a concrete sense of verisimilitude.

However, those are minor quibbles in what is another strong, insightful and moving addition to a stunning body of work.

And at least we’ve got a week off before his next book hits the shelves (Loverboys, out from Dark Horse on October 1!).

Gilbert Hernandez (W/A) Drawn and Quarterly, $21.95, September 2014.