Charles Forsman rounds off a banner year with Celebrated Summer, an affecting trip through teenage ennui.

The name Charles Forsman has been cropping up in a lot of end-of-year lists over the past couple of weeks, including our own Broken Frontier Awards. Looking back at the 2013 he’s enjoyed, it’s no surprise.

His highly acclaimed mini-comic The End of the Fucking World was collected and published by Fantagraphics, and is also being made into a web series starring Craig Roberts (Submarine), with the backing of the UK’s influential Film 4.

Meanwhile, Teen Creeps, his current mini-comic project, is also receiving acclaim, and his publishing and distribution imprint, Oily Comics, continues to put out a range of interesting material on a monthly basis, landing him a nomination for Best Publisher in our awards.

Now Fantagraphics has rounded off the year by publishing Celebrated Summer, a 68-page tale featuring two typical Forsman protagonists – a pair of disaffected teens, Mike and ‘Wolf’ (real name Carl), who drop acid and go for a spin in Mike’s car, first to the countryside and then to a nearby down-at-heel beach resort.

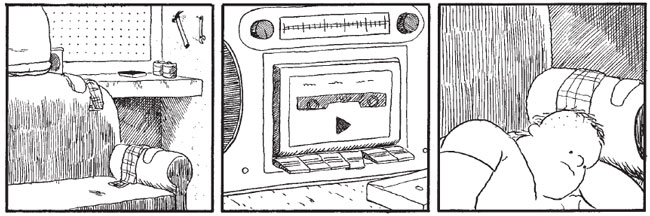

Celebrated Summer shares its title with a Husker Dü song from 1985, which probably reflects the period of the story, given the lack of mobile phones and the fact that Wolf still listens to tapes.

The song also shares the tone and subject of the book, casting a nostalgic but sardonic look back to the long summers of youth – a time when “getting out of school meant getting out of hand”, before the onset of winter meant that “summer barely had a snowball’s chance in hell”.

The book was actually written and drawn before TEOTFW, and offers a much more ‘gentle’ narrative. There’s a clear similarity in that its protagonists are two young people feeling themselves at a tangent to society, but here they’re not quite as removed as they’d like to think.

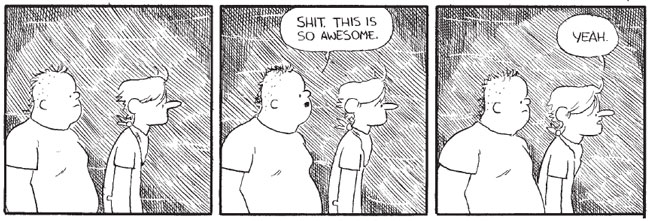

Indeed, the book’s main beauty is its level of understatement. Its teenage characters don’t rail, Holden Caulfield-style, against adult hypocrisy. Instead, the world they kick against actually seems fairly benign. (Even Mike’s exchange with a traffic “pig” is actually a friendly chat about directions.)

Their sense of ennui is more internal and depicted more subtly. When Mike asks Wolf how he feels about finishing school, the ambivalence of his reply is telling:

“I kinda don’t feel anything. It’s just sort of ended, man… I think it finished a long time ago… in my head.”

In fact, the touching and compassionate characterisation of Wolf is the axis around which the rest of the book rotates: an awkward young man trapped in an unwieldy teenage body and feeling excluded from the world around him.

The details are never spelled out, but somehow his family has fragmented, leaving him living with his grandmother and clearly isolated and damaged.

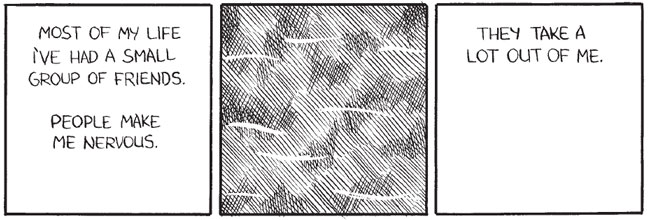

In a startling two-page interlude about midway through the book, we get another snippet of reflection from the older Wolf that again illuminates much of what we see:

“I’ve always been big… I pretty much quit playing at recess after I accidentally broke Tom Miller’s arm during a football game. After that I got really quiet. It felt safer just to watch.”

Several times throughout his and Mike’s brief odyssey, it seems that Wolf wants nothing more than just to return home. At one stage he calls his Grandma while he’s tripping to let her know he’s OK, but his nerve fails him and he hangs up. A simple scene featuring the two in a shoe shop, late in the book, speaks volumes about their relationship, and the only flash of anger we see from him throughout the book is in response to Mike’s nonchalant dismissal of his own grandparents.

The measured approach of the narrative also extends to the depiction of the pair’s experience on LSD. Forsman’s low-key cartooning eschews the visual extravagance that normally goes with the term ‘psychedelia’ to focus on the more subtle alterations to their perceptions.

At one stage Mike finds himself ‘mentally undressing’ a chocolate bar at a service station; as his attention to his surroundings fades away, so does the rendering of the background. Later, he finds himself regarding a plant and seeing it bloom in fast-forward.

Wolf’s trip reaches its zenith amid the overstimulation of a video-game arcade, taking the form of a detachment into a world of geometric patterns that reinforces the ‘circle’ motif that recurs throughout the book. (Interestingly, that scene works very well in the digital format, with the instant on-screen page transition and the persistence of vision creating an interesting visual effect.)

Rather than blowing open the Doors of Perception, the lads’ trip – in both the literal and psychological senses – highlights the boundaries of their existence. Wolf can’t – and maybe doesn’t even want to – break the umbilical cord that connects him with home. And when Wolf visits Mike back at his McJob the following day, it’s clear that the latter has also returned to his repetitive daily existence.

Throughout, the circle acts as a constant reminder of the sense that the characters aren’t really getting anywhere, but going round in a loop. As they head for a doughnut shop to ease their late-night munchies, Wolf reveals that he’s “been thinking around in circles all day”.

As well as the difference in intensity between the two books, Celebrated Summer is also slightly removed from TEOTFW in its art style. Indeed, Charles Forsman has said that the latter – much more stripped down, in rendering as well as page size – was a reaction to the altogether busier style of the former.

Nevertheless, the power of Forsman’s art lies in its simplicity; in particular, he captures perfectly the adolescent awkwardness of the lumbering Wolf. In one frame, as the drug starts to get a grip on him in the video arcade, his beffuddled face is even a dead ringer for that of Poor Ol’ Charlie Brown.

The book concludes with a heartbreaking return to the ‘present day’ Wolf/Carl, fearful about life and reflecting on his youth: “I do still lie awake at night. Strangled with nostalgia. How can those days be so far away.”

It’s an affecting conclusion to one of the most quietly powerful comics I’ve read for some time.

Charles Forsman (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $16.99, December 2013