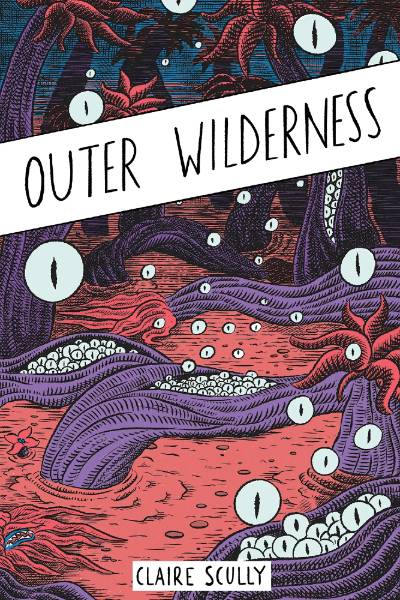

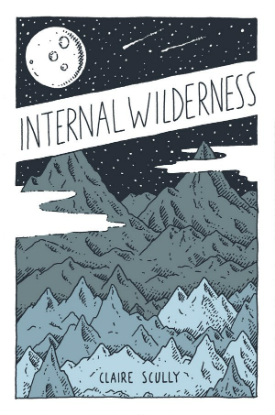

SLCZF WEEK! Redefining how we think about psychogeographical comics, Claire Scully’s Wilderness trilogy came to a conclusion last month with the publication of the third and final part Outer Wilderness from Avery Hill Publishing. Each standalone, though thematically linked, instalment in the series (Internal Wilderness, Desolation Wilderness and Outer Wilderness) has challenged our preconceptions of the definition of sequential art and graphic narrative through their explorations of landscape and environment.

With Outer Wilderness making its in-person debut on the Avery Hill table at this weekend’s South London Comic and Zine Fair we caught up with Claire to chat about her very distinctive approach to the medium…

ANDY OLIVER: As this is the very first time we’ve interviewed you at Broken Frontier can you tell us a little about your artistic background and practice to start?

CLAIRE SCULLY: So I often describe what I do as being a commercial illustrator, as it is the main part of what I do for a living and it allows me to work on a variety of different types of creative projects. Most recently I have been working on quite large scale museum projects for their permanent exhibitions and displays, but I also do a fair bit of editorial and publishing work too. My own journey into the creative world was full of happy accidents and taking opportunities when they came up.

I come from a working class background and grew up on a council estate in North London, so never really had an exact idea on where I was heading, really didn’t know what the possibilities were. I had originally set out to become a photographer as that was kinda the only creative ‘job’ I understood, but didn’t get offered a place at the university I applied to. However my tutor at the time was intent on me doing a degree so got me an interview for a place on the illustration course at London College of Communication. The course had a very broad approach to what ‘illustration’ could be and I guess it all snowballed from there.

I went on from there to do a masters degree in Visual Communication (illustration pathway) at Central Saint Martins which was where I was encouraged to embrace all the things that interested me – this was where I first began to explore science fiction actually. I studied a little later than everyone else and spent about 5 or 6 years working full time after I left school, so when I eventually got back into the institution of education I was really determined that this was going to become my job. I really threw myself into it.

I am also an educator, teaching illustration at the University of Brighton which is something I am really passionate about. For me Art School was AWESOME and just opened up a world of opportunity that I had no idea existed, I had some incredible tutors along the way that challenged and pushed me to finding my place and making it my own. I’m a little bit romantic about the whole thing but it was such an important part of my journey.

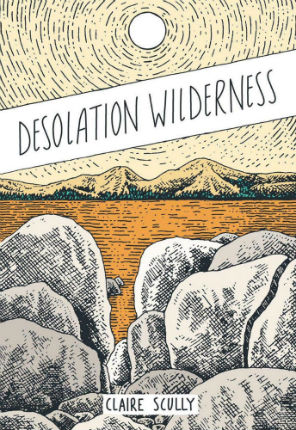

AO: Before we talk about Outer Wilderness what was the premise of the first two books in the Wilderness series and what were the themes you were looking to explore in them?

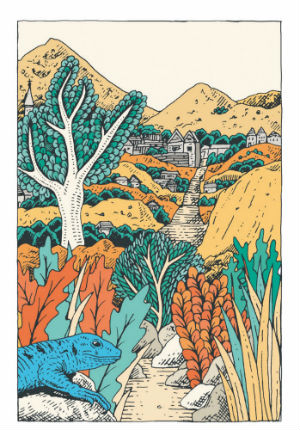

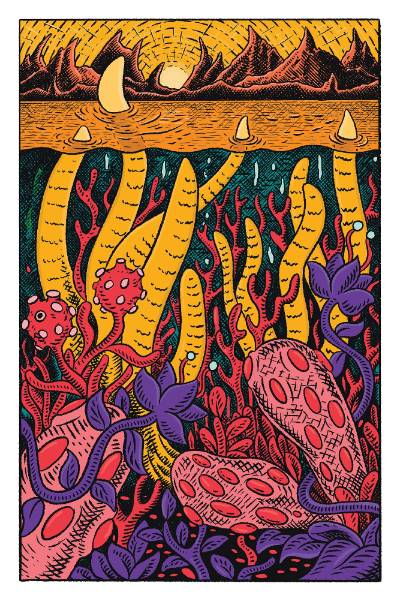

SCULLY: I always seem to gear myself to work in a series, I can never just leave things as one image, I like to build worlds and that’s kinda what happened with these books. All three books have quite a distinct approach to them while still retaining a sense of a set. In the Internal Wilderness I liked the idea of internal landscapes from your imagination that are formed from personal experience and memory, over time these places become quite fantastical and nostalgic.

SCULLY: I always seem to gear myself to work in a series, I can never just leave things as one image, I like to build worlds and that’s kinda what happened with these books. All three books have quite a distinct approach to them while still retaining a sense of a set. In the Internal Wilderness I liked the idea of internal landscapes from your imagination that are formed from personal experience and memory, over time these places become quite fantastical and nostalgic.

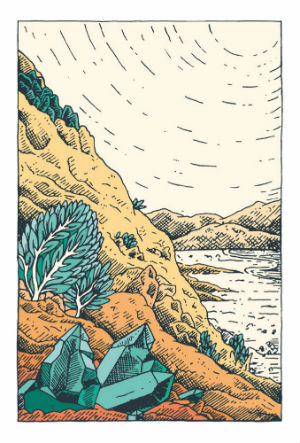

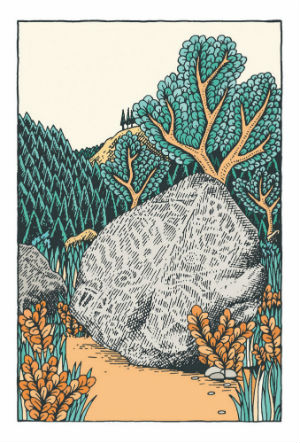

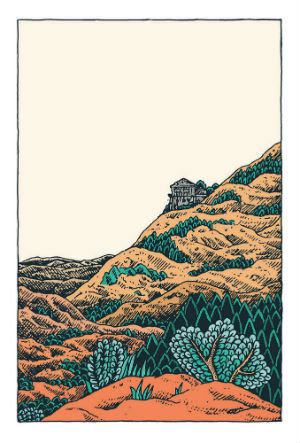

As I moved into Desolation Wilderness I opened up to a more direct connection to more recent experience and how we record and remember the atmosphere or sense of ‘place’. I was fascinated with the fact that it was a real place on a map but without any tangible boundaries, like I never really knew if I was there or not, but it was also about memory and experience on a personal note – how to capture the sense of a place or the atmosphere. It’s not essential for a replication of a scene but somehow creating images from how you remember them to be often allows more people to identify with the images and make connections to their own experiences of places like this.

AO: There’s been an interesting gradual shift from the psychogeographical to the speculative over the run of the series. What was the impetus for moving from the reflective and the personal of the first two books to the fantastical in Outer Wilderness?

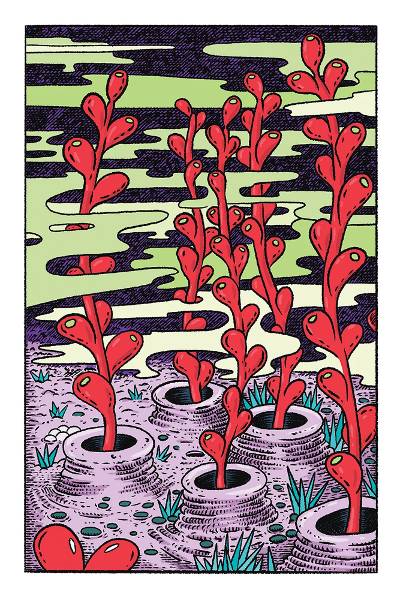

SCULLY: I think its really important to keep challenging your ideas and to keep feeding your process with other possibilities or ways of thinking about your themes. This said, the Outer Wilderness still feels like a personal journey for me, almost like I’m speaking to the imagination of my inner child that doesn’t need rational explanations just allowing my work to be playful. I think the landscapes in this book connect quite deeply to our own mental landscapes, I was thinking recently about how we tackle tricky or treacherous terrain both in the real world but also that which we create in our heads. Outside of this this series also allowed me to contemplate the existence of life in the universe, an existential exploration in an infinite reality.

AO: What have been some of your inspirations for the eerie landscapes and alien worlds of Outer Wilderness?

SCULLY: I will watch absolutely anything relating to astronomy, without any filter for the good or the bad, I particularly love the overly dramatic ones like ‘how the universe works’ – they will show all the myriad ways in which you will die on all the various worlds they talk about. So I was trying to give myself the space to explore these worlds without my eyes exploding or my blood boiling.

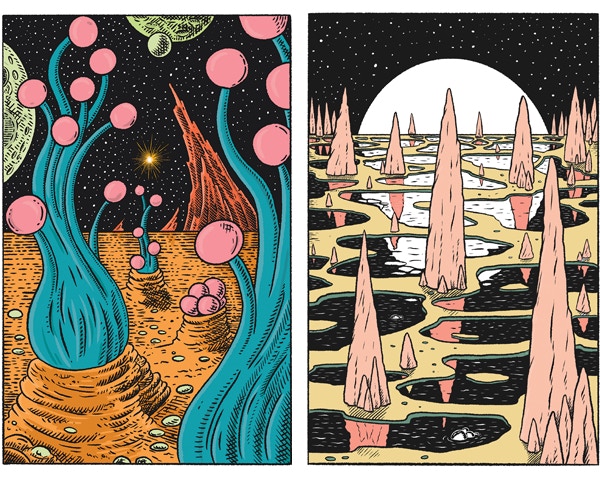

Halfway through the making of this book I happened upon an old educational Disney animation called Mars and Beyond made in the 50s which was used to teach children about the possibilities of Martian life. I loved how bonkers the ideas were of what Martian life could potentially be like. So much science fiction bloomed from this period and for me I love depictions of space and the different ideas about how to convey alien worlds; Robinson Crusoe on Mars is still one of my favourite 60s sci-fi films for this reason. Often these landscapes would have a very recognisable earthly feel to them except for the use of a more surprising colour palette or the gigantification of particular elements, so for my own worlds I still wanted them to feel organic and natural but just not earthly.

AO: One of the things that I find most interesting about the Wilderness books is the way in which you invite the reader to create their own narratives around the environments you depict. How important is that interpretive element and the very distinct communicative relationship it fosters between artist and audience to you?

SCULLY: It is really important to me, a long time before I made any of these books when I was still developing my worlds I made a drawing of an imagined landscape and I think someone commented with how they wanted to walk there. This really struck a chord with me. I love how you can experience the same space/place in a completely different way to another person, and how important it is to allow people the space to be able to experience things in their own way.

How you feel internally and your own unique filter can dramatically affect how you experience the world around you and the same can be said for objects, books, films, art, music, etc. I’d like to think of it as a conversation and for my work to spark creativity in the viewer, I’m sure there will be explanations for giant plumes of red smoke oozing out the glowing cracks of a fracture valley that will far exceed my rationale.

Coming from the perspective of an illustrator and practising visual communicator, making my images accessible for people is at the core of my practice, inclusivity with my visual language and offering a warm welcome into a potentially unfamiliar world, hopefully aiming for the viewer to feel like they should be there. This possibly links a little to my issues with class systems which opens up a whole other topic, but it all connects.

AO: Let’s talk about your creative process. The first two books were drawn in pen and ink. Why did you switch to working digitally for the third book?

SCULLY: I think it was a simple solution to managing my time, I was juggling quite a lot of different projects and teaching during the creation of this book, so I was needing to fit each page in around my other illustration work. For me, these pages were classed as part of my ‘down time’ mostly because they are so enjoyable to draw, so it was purely a choice that made sense for me to be efficient.

Digital drawing and analogue drawing are two very different beasts. I have a theory that maintaining an analogue drawing practice will make you a better drawer in whatever media be it digital or analogue, whereas a digital drawing practice will increase your digital drawing skills but it will not make you a better drawer when you pick up a pen/pencil. So, though I do love drawing digitally my heart is always with the analogue process first. With pen and paper you have to accept a bad drawing and learn from it, with digital there is the ability to constantly remove or adapt your lines.

AO: You’ve adopted different colour palettes for each of the Wilderness books. What were you trying to evoke in terms of mood and atmosphere with those choices?

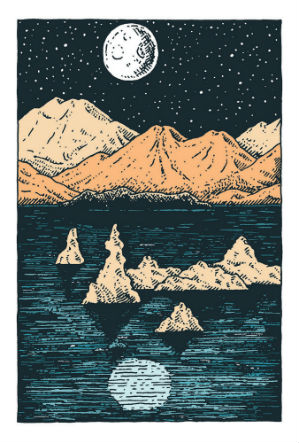

SCULLY: Yeah, I think the colour has played a very important part in how this series of books has developed. In the Internal Wilderness I used a monotone of blues, they were nocturnal images but they were also connected to distant memories and nostalgia so this felt a little like looking back, recalling dreams or imagined places. Then for the Desolation Wilderness book because this was based on a real place I moved into a more complementary colour set – still quite muted, a bleached-out and limited colour palette that you find in the desert. Again not too far removed from how you might remember a place to be, not necessarily picturing the exact right colours but ones that match your experience of it. So for this final book in the series I allowed a much larger range of colours and opened up for clashing and saturation. In theory they should work as three standalone books and though each one feels very different they still make a lot of sense as a set.

AO: And, finally, now that this trilogy has been completed are there any other upcoming projects you’re working on that you can tell us about?

SCULLY: I always have a few things rumbling away, I’m still working on a book called Parkland that has been an ongoing project for the last few years – it’s a bit of a documentary illustration project that sits within the comic book genre but has the feel of a photographic Artist Book? If that makes sense… It is currently without words but I’m playing around with some possibilities with that, how I might add a narration.

I made a work-in-progress version of this a while back and have a short zine publication available with a selection of drawings from the main project but it’s remained unfinished for me still. I’ve also got a few little fun projects on the side that I’m playing around with – interpretations of classic movie monsters is one and a series of drawings to form a myriorama.

Outer Wilderness is available from the Avery Hill Publishing online store.

Avery Hill are at Table 34 at the South London Comic and Zine Fair this Sunday July 10th.

Interview by Andy Oliver