As nicely presented as it is, Dan Mazur and Alexander Danner’s ambitious chronicle of modern comics history doesn’t quite live up to its billing.

1968: now THAT was a momentous year. The Prague Spring, the murders of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, student insurrection on the streets of Paris – not to mention the unpromising arrival of yours truly and a brief sojourn at the Home for Friendless Catholic Children in Liverpool (but that’s another story…)

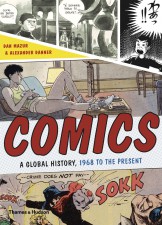

Anyway, according to Dan Mazur and Alexander Danner, the authors of Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present (published by eminent art and design imprint Thames and Hudson), it was also “a watershed year in which a number of comics creators in Japan, America and Europe began to aggressively demonstrate that comics could be more than an ephemeral vehicle for children’s entertainment.”

Anyway, according to Dan Mazur and Alexander Danner, the authors of Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present (published by eminent art and design imprint Thames and Hudson), it was also “a watershed year in which a number of comics creators in Japan, America and Europe began to aggressively demonstrate that comics could be more than an ephemeral vehicle for children’s entertainment.”

And their dense 320-page volume is an ambitious effort to trace the development of the Ninth Art into the diverse global smörgåsbord / mezze / thali / buffet from which we’re eagerly filling our boots today.

However, as the authors admit, the selection of even such a significant year as 1968 as a comics watershed is somewhat arbitrary, seemingly hung first and foremost on Robert Crumb hitting the acid-drenched streets of Haight-Ashbury with a baby carriage full of Zap #1.

Indeed, the book’s introduction puts it a bit more firmly in the wider context of the post-war period, in a world dealing culturally and psychologically with Auschwitz and Hiroshima, and demographically with the arrival of the baby boomers (who creatively populate at least the early part of this book).

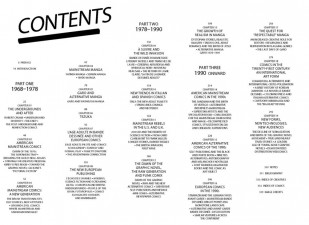

It’s probably also worth mentioning here that three dominant comics cultures are at the heart of what Mazur and Danner treat as ‘global’: Francophone Europe, Japan and the US. And the early chapters hit the ground running to provide a chunky survey of what was happening in the late 1960s in those creative landscapes.

For the fact-hungry panelologist, the opening chapters on each of those comics cultures are very engaging, daring you to memorise every key work, creator and date. It seems clear that Mazur and Danner understand comics readers’ thirst for encyclopaedic knowledge, even outside the mainstream collectors’ mentality.

The geographical coverage is subsequently opened up a bit, highlighting – for example – trends in Spanish and Italian comics. But while that’s a welcome addition, the section is disappointingly brief: only seven pages, three of which are full-page reproductions of art (all Italian).

Given what Pedro Almodovar and his peers were up to in Spanish film in the immediate post-Franco era, it’s hard to imagine that comics didn’t also have more of a movida.

Also, in a book that’s keen to put developments in comics in the context of social change, it’s noticeable that there’s little or nothing relating to the biggest political shift of the period covered by the book – the break-up of the Soviet Union and the fall of communism in central and eastern Europe.

Maybe there wasn’t much in the way of comics culture in these countries before or after the wall came down, but given the seismic cultural shifts of perestroika and glasnost, surely there must have been something to say.

The book also has a few more practical flaws in terms of production glitches, such as repeated text, typos and misplaced captions. More problematically, there also seem to be a number of factual errors. I’m certainly no expert on global comics – which is why I was so eager to devour this book – but in the areas I do know something about, I found a few bloomers.

The book also has a few more practical flaws in terms of production glitches, such as repeated text, typos and misplaced captions. More problematically, there also seem to be a number of factual errors. I’m certainly no expert on global comics – which is why I was so eager to devour this book – but in the areas I do know something about, I found a few bloomers.

For instance, the anthology Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia (AARGH!), published in the UK in the late 1980s by Mad Love (Alan Moore, his then-wife Phyllis and their mutual lover Debbie Delano), is described as “Steven Appleby’s anti-homophobia anthology AARGH!” (Appleby was just one of many contributors.)

Elsewhere, Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s Zenith is referred to as “The UK’s first American-style superhero comic”, overlooking its cynical tone and deconstructionist approach, as well as the fact that it was published serially in 2000 AD.

We’re also told that Marvelman was “known originally as Miracle Man“, while poor old Action – representing a key moment of controversy and development in the British comics scene of the 1970s – gets no mention at all.

But it’s not just me being a Little Englander, either: at a time when the world of comics is particularly exercised by the treatment of female creators, it seems more than a little hamfisted to get the gender of Dylan Meconis wrong.

This all probably sounds like a bit of a hatchet job on the book, but evident flaws like those cast a pall of doubt over some of its other assertions.

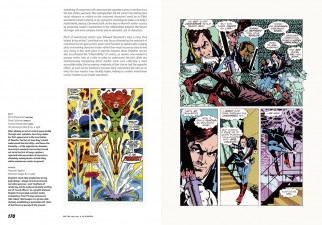

Nevertheless, despite its problems, the book’s scope and its authors’ ambition still make it an attractive addition to the reference shelf. If nothing else, its 289 colour and black-and-white illustrations allow a lot of the work to speak for itself, highlighting the unique nature of comics as an almost infinite index of stylistic possibilities.

Dan Mazur & Alexander Danner (W) • Thames & Hudson, £19.95, June 2014

A less than enthusiastic review, Tom, so I’m going to cross this from my list.