There is something extremely perceptive about Luke Healy’s response to a question about what he expects readers to take away from his work. He says he wants them to make sense of experiences he is trying to communicate and use them to explain how they feel.

Healy is more than equipped to pull off these exchanges of information, given his background in journalism and stand-up comedy. It’s also how his new book, The Con Artists, balances empathy towards his two male protagonists with wry commentary on the state of our world. It questions the thin line we collectively draw between success and fraud, epitomized in the lives of real people who find fame for acts of wilful fraud.

We asked Healy a few other questions, about his approach to dialogue, themes he tends to gravitate towards, and whether he ever fears causing offense. Here are his responses.

BROKEN FRONTIER: Your background in journalism and cartooning gives you access to some unique and undeniably powerful tools with which to engage with the world. How do you go about deciding what kind of project you intend to work on?

LUKE HEALY: I think that each book I’ve made has been an attempt to capture the feelings of a certain period of my life— some more literally than others.

I’m a bit of a repressed guy (many thanks to the emotional communication skills taught in ‘90s Catholic Ireland), so writing these books is my attempt to communicate complex or subtle feelings about experiences I’ve had. It’s hard to say how something sustained, and complicated, felt in a just few words—but maybe if I write a book that takes people along for the journey with me, they’ll come out the other end with an understanding of what it was like.

BF: Much of what makes Frank and Giorgio in The Con Artists so real and compelling is their dialogue. How does a cartoonist go about preparing for that aspect of creating a comic?

HEALY: I’ve always enjoyed writing dialogue, and that enjoyment has only increased since I started writing and performing live comedy a few years ago. There is something so satisfying about nailing a joke’s structure either on stage or on the comics page.

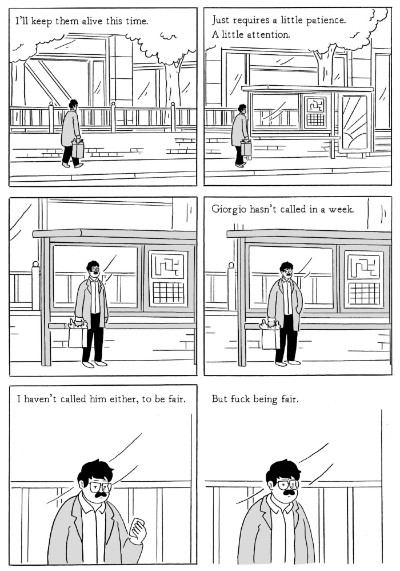

As I write characters’ dialogue, I try to keep their point of view in mind. What’s the flaw in their way of seeing the world that is the source of the comedy for that character? In The Con Artists, Giorgio is manipulative, and Frank is anxious—it all comes back to that!

BF: Friendship and fraud appear to be compelling themes for you. How to Survive in the North, for instance, examined both to a certain extent. What draws you towards exploring these aspects of human nature?

HEALY: I suppose as someone who was very meek and anxious growing up, I felt like I was often talked over and overruled by more confident people—and that frustration is fun to write about. But characters in my books, like Bartlett in How to Survive and Frank in The Con Artists, also have a self-assuredness. They’ll be pushed to agree with these fraudsters, but only to a point. It’s fun to write quietly confident characters, I suppose. They feel powerful in their own way.

BF: A recent reader review of The Con Artists online complained that “not a lot of questions were actually answered.” One suspects that was always the point, but it makes one wonder what you expect your audience to take away from your work in general?

HEALY: Primarily, I want people to be entertained by the books. But also, I want people to feel a sense of connection, as I said above—to understand me better, I guess, which is a bit of a selfish goal.

I remember reading a book about marketing once and tried to think about my comics as “content” as they described it. They asked the question “what service is your content providing to someone?” and I decided that my goal with my comics is to communicate an experience in a clear, emotional way, so that anyone who has had a similar—and hard to communicate—experience, can hand someone my book and say “this is what it felt like”.

BF: Humour is now a topic fraught with danger, given the times we live in. Do you feel constrained to curb your enthusiasms for fear of causing offense?

HEALY: I suppose I disagree with the premise of the question. I think that comedy has never been a freer medium than it is right now. If I’d gotten on a stage 20 years ago and performed my material about what it’s like to be a gay man, I’d have been booed off the stage, or worse.

I’ve never felt inhibited, because all of my jokes are about the only thing I know—myself. How could I offend someone? I’m speaking honestly about my experience of being Luke Healy in the world. If other comedians want to get on stage and mock strangers for an easy laugh, then they deserve to get push back.

And besides—what dangers have these “cancelled” comedians faced for their offensive jokes? They’ve all been paid millions of pounds to produce more comedy specials. I’d love to be cancelled. Sounds extremely profitable.

BF: You posted a hugely entertaining comic about being stuck on a train with Serbian cheese smugglers a couple of years ago. What smaller side projects are you currently involved in, now that The Con Artists is out in the world?

HEALY: Right now, I’m working on large projects only, which is sad because I love to make shorter comics to post online. But for the last couple of years, besides comics, I’ve been working in TV development as a writer and show creator—I have a couple of projects on the go for that side of things, so hopefully one of those will eventually find its way to screens!

BF: You have recommended the work of Pascal Girard, now an established artist, in the past. Are there new and upcoming artists you would like your own readers to pay more attention to?

HEALY: I recently read a series of minicomics called Biggol by Ioan Morris that I thought were amazing. He’s a Welsh cartoonist— and the comics are a fictional oral history of a Doctor Who-esque show. They’re so funny and fresh and just a pleasure to read. They’re available from CPE Books!

Published by Drawn + Quarterly in North America

Published by Faber in Europe

Interview by Lindsay Pereira