Lewy body dementia (LBD) isn’t a condition we hear a lot about in the media. Although Robin Williams’ recent post-mortem diagnosis shone a brief spotlight on the illness, LBD remains unknown to most of the general public. Its connection with the more notorious Parkinson’s Disease and increased awareness about mental illness in general will hopefully translate into more education and research. For the time being though, it’s pretty slim pickings.

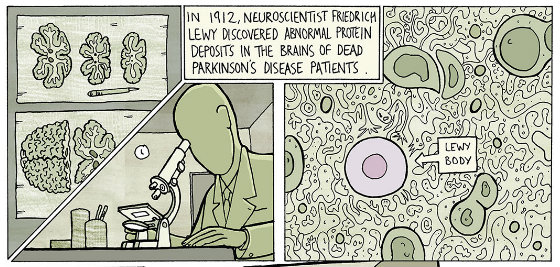

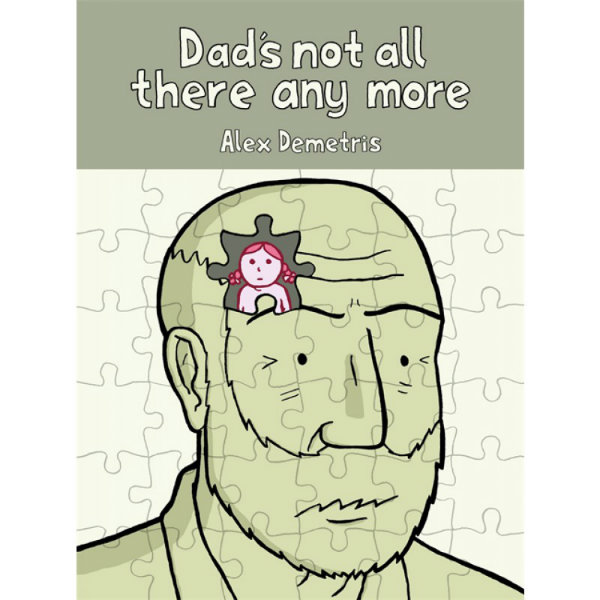

That’s why works of graphic medicine like Dad’s Not All There Any More by Alex Demetris are so important to the ongoing discussion around lesser-known medical conditions like LBD. Although it began life as his final assignment in art school, the graphic novel’s humour and insight have helped to spread awareness of the disease in an unintimidating and accessible format.

That’s why works of graphic medicine like Dad’s Not All There Any More by Alex Demetris are so important to the ongoing discussion around lesser-known medical conditions like LBD. Although it began life as his final assignment in art school, the graphic novel’s humour and insight have helped to spread awareness of the disease in an unintimidating and accessible format.

Debuting a couple of Fridays ago at Gosh Comics in London, as part of Singing Dragon’s graphic medicine initiative, Demetris’ book is a wonderful example of the subgenre of graphic memoir, providing a snapshot of the unique challenges that families stricken by LBD face on a daily basis.

Demetris spoke with us via email about the puzzling nature of LBD and how his family managed to cope with the disease with such grace and good humour.

Lewy body dementia is one of those conditions people only learn about when someone famous is diagnosed (I believe Robin Williams was recently revealed to have been afflicted by the disease, after his death). How important was it to you to tell your story to a wider audience?

You’re right that Robin Williams was revealed to have had LBD, and it did seem that this sad turn of events raised the profile of the condition (though not hugely). I remember watching a pretty awful, voyeuristic TV documentary about Williams’ death just to see what was said about LBD. Like I say, it was an awful documentary, but I was quite excited when it included an animated graphic to explain how the condition worked, as I had never seen anything like that before on LBD.

Turning to your actual question – as you may know, I produced the comic for my MA at Camberwell College of the Arts. I needed to come up with a final project, and having thought about a few ideas, it seemed silly not to make a comic about what was going on in my family at the time.

I had never really wanted to talk about the nitty-gritty of our experiences with my friends, and in a way it was easier for me to explain it in the form of a comic. Before my MA, I had worked at the UK Department of Health for a few years, so I had a strong understanding of the importance of educating people about health issues.

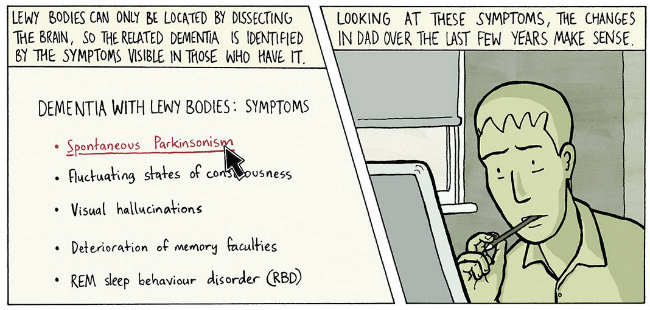

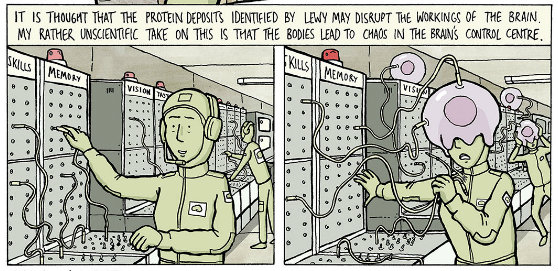

I therefore wanted to include an educational/informative element in the comic, as the condition is not so well known (I had not heard of it before Dad was diagnosed). But I also wanted to present this within a reasonably entertaining, readable comic.

With regard to the comic telling a story to a wider audience, I think it is important that health information is spread as widely as possible, so if it reaches lots of people through my comic then that is great. However, when I was creating the comic I was focused mainly on taking the opportunity of the MA to challenge myself to make a good piece of work. If people like it, and find it informative and well written/drawn, then I am very happy.

In spite of the obvious challenges your father’s condition presented your family, you seemed to find humour in the different way in which he perceived the world. How did you manage to keep negativity at bay?

When you’re going through a rough time, I think that you often become very focused in the moment. With my Dad, he obviously wasn’t going to get any better, but I never really thought too much about what his future held – instead I just tried to concentrate on making the most of him whilst he was about.

I would argue that this actually worked pretty well – I made sure I was very much involved in his care (though my mother did most of the hard work, with sterling support from my aunt and uncle especially), and I look back on his time in residential care fondly – I enjoyed visiting and seeing what staff and other residents were up to.

I would argue that this actually worked pretty well – I made sure I was very much involved in his care (though my mother did most of the hard work, with sterling support from my aunt and uncle especially), and I look back on his time in residential care fondly – I enjoyed visiting and seeing what staff and other residents were up to.

With regard to humour, I think that it is a natural way of dealing with difficult situations – who wants to sit around being miserable and poignant? It’s much more helpful to have a bit of a laugh.

As for my Dad’s perspective on the world, he would sometimes make extremely random statements out of the blue, and it could be very funny. Before his illness he could be extremely funny, so I think to a degree I see the humour and odd statements as being indicative of the remnants of his personality, which frequently shone through the illness.

Also, if you’re visiting someone in a care home, you want them to have a good time, so it seems natural to me that you’d want to have a humorous atmosphere.

As someone who has witnessed first-hand how Lewy body dementia affects its victims and their families, what advice would you give to those giving care to loved ones coping with the disease?

Firstly, a bit of a disclaimer in that I can only really comment based on my own experiences – no two people will have the same experience of the condition.

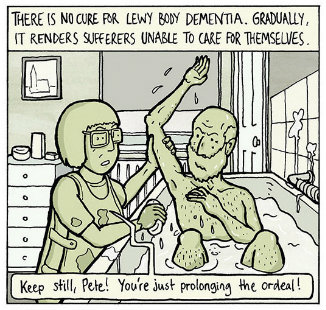

I would advise carers to make the most of any care resources available. Caring for someone with dementia is extremely demanding, and people who are primary carers to those with these kind of conditions should not be ashamed or embarrassed to ask for help.

Another thing that struck a chord with me was that other people always seemed to be obsessed with the idea of Dad not being able to recognise us. I decided early on not to worry about this – when you are visiting someone with LBD it is about them, not you, so worrying about how they perceive you is counter-productive.

I suspect that some of the time he did recognise me, and sometimes he did not, but constantly wondering about how well someone recognises you could drive you mad! Better to just get on with the caring process and enjoying what you still have (though I should emphasise here that what I say here is based solely on my own experience, and that my mother was Dad’s primary carer).

I suspect that some of the time he did recognise me, and sometimes he did not, but constantly wondering about how well someone recognises you could drive you mad! Better to just get on with the caring process and enjoying what you still have (though I should emphasise here that what I say here is based solely on my own experience, and that my mother was Dad’s primary carer).

Also, I wanted to use the comic to explain that having a relative put in residential care is not necessarily a bad thing. I think a lot of people view this as a terrible thing to do, but in our case it was a relief, and Dad seemed content in his home.

Of course, you need to find a decent home – I think it a disgrace that in the UK more public funding is not available for residential care homes, and that it is a real shame that they tend to only be in the public consciousness when something bad happens, such as news stories of abuse. There are some amazing people doing great work for very little pay.

Additionally, I would advise people to make the most of their loved ones even once the dementia has taken full hold; they still have lives, even if these are different and diminished.

Another important thing to do is to ask health staff questions about the care they are providing, and to question it whenever you feel it is necessary to do so. Finally, if the person with dementia is in residential care, I would advise carers and loved ones to visit as often as possible.

Education was an integral part of your coming to terms with your father’s condition. but there’s a heck of a lot of it out there and the search can get confusing, to say the least. Where did you find your most reliable sources of information about Lewy body dementia?

To be honest, I wasn’t given that much in the way of education while my Dad was ill. My Mum attended his medical appointments and would report back. I actually wish I had made more of an effort to investigate the condition myself, rather than relying on her information. So in a way, the sequence in which John is shown looking up information on the internet is what I feel I should have done.

I would definitely suggest that anyone affected by the condition does their own research, and I would start with organisations such as the Lewy Body Dementia Association (www.lbda.org) and Lewy Body Society (www.lewybody.org) in the UK. I included these websites in my comic as it is essential that people are swiftly directed to the best sources of health information available.

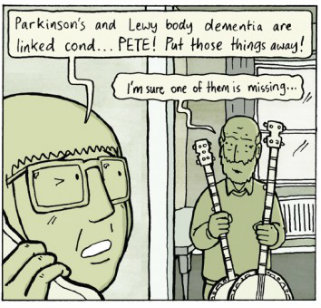

The metaphor of the puzzle runs throughout the book, with pieces even serving as chapter illustrations. Why did you choose the puzzle as a central metaphor? Does a condition like Lewy body dementia allow for a complete picture of its effects upon its victims and their families?

The puzzle motif was quite a late addition to the comic. My Mum used to do puzzles, and there is a panel in which you see Sue being distracted from her puzzle by Pete. It occurred to me that puzzles were a good metaphor for Dad’s condition, as it felt like it was resulting in him having ‘missing pieces’- i.e. a lot of him was still there, but bits were disappearing as the condition took hold.

The comic also ends with a mention of missing pieces – this idea just seemed to fit the story like a glove. I find puzzle pieces to be quite visually pleasing shapes, so I decided to use the puzzle motif throughout the book to give it a sense of visual continuity.

Graphic medicine – comics that seek to heal or educate – is a relatively new label for stories that address how we cope with a wide range of physical and mental ailments. Often readers are more concerned about what they can take away from a story, bringing with them their own set of experiences to the stew, but how cathartic or therapeutic is it for the creator to revisit these kinds of intense memories?

It was definitely therapeutic for me – as I mentioned, I did not really speak to my friends about my family’s experiences of dealing with Dad’s condition. Not necessarily because it would have upset me, I just didn’t really want to. Therefore, it was good to get down in comic form the kind of things that were happening.

It is also therapeutic to feel that you are sharing experiences that may be useful to others, though at the time I had no idea how widely the comic would be read. But yes, it was definitely therapeutic to create a visual depiction of the kind of things that had happened.

How much did creating this graphic novel affect how you viewed your family’s struggle with Lewy body dementia – if at all?

I don’t think it affected the way I view my family’s response much, to be honest, though it is nice to have a bit of a visual record, albeit fictionalised, of what happened. Dad’s illness really unified the family, and I look back on the period he was in residential care very fondly.

I suppose that when I look at the comic it shows how intense the whole experience was for my mother, Dad’s primary carer, so it is a bit of a testament to her efforts, as well as to my Dad’s personality.

What do you hope people take away from your experiences?

I hope that they find the comic educational and informative, but also that they find it to be entertaining and enjoy the story and getting to know the characters. This was my first attempt to create a substantial comic of reasonable length and dealing with important issues, so it was very much a learning experience for me.

I wanted to embed important information in a readable, enjoyable story, so I hope I have been successful in doing so.

With regard to LBD, I suppose the bottom line is I hope that the comic spreads awareness of the condition and helps to demystify it a bit. I also hope it shows that even with a horrible illness like LBD you can make the most of the person who has it while they are still around.