Our Inside Look feature at Broken Frontier provides creators with the opportunity to share exclusive commentaries on their comics projects with our readers, giving insights into the genesis, process and themes of their work. It’s one of the oldest regular features at BF, first appearing on the site back in the mid-2000s and also one of our most well-received.

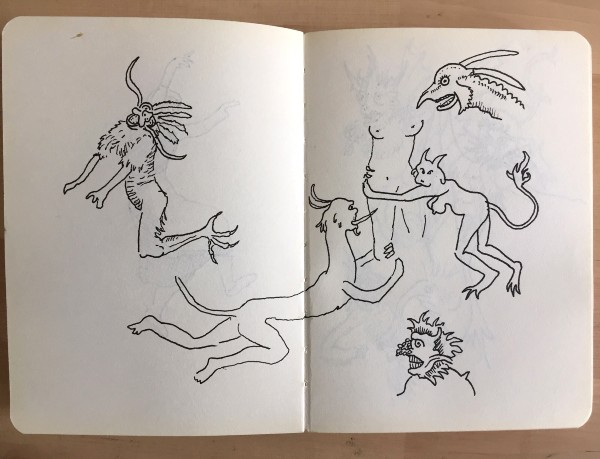

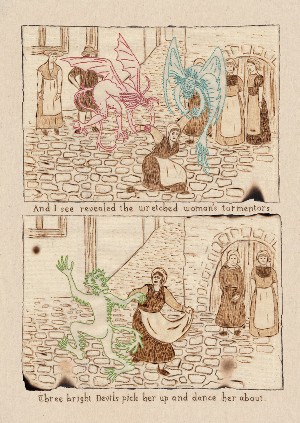

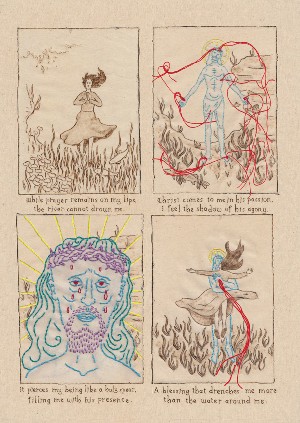

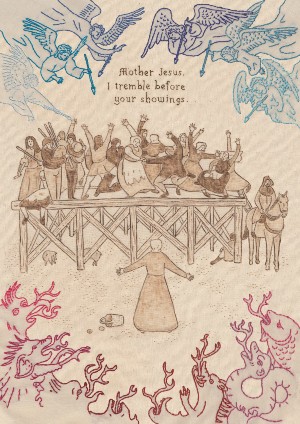

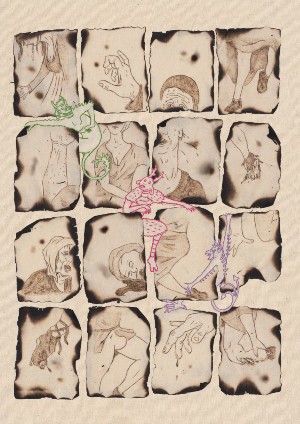

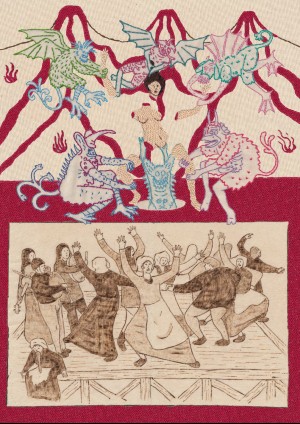

Image above – Finished interior pages from The Dancing Plague

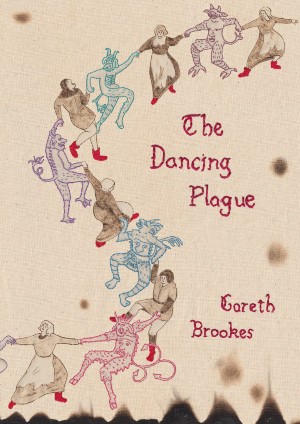

Today’s commentary comes from much-featured artist Gareth Brookes who talks about his most recent graphic novel The Dancing Plague, published by SelfMadeHero and reviewed recently here at Broken Frontier.

I first heard about the dancing plague of 1518 from an article online somewhere. The famous rapper Drake had just released a viral video involving him leaping out of a moving car whilst dancing in a stylish and seemingly effortless manner. Copycat Tik Tockers were injuring themselves in their thousands. The article was about the most dangerous dances in history and the dancing plague was number ten.

The 1518 dancing plague (I read as I feverishly Googled) was one of many such medieval events, wherein ordinary people had the sudden compulsion to dance. This compulsion spread around the population like a contagion, until hundreds of people were dancing themselves into a state of collapse or even death.

Bruegel the Elder’s depiction of a dancing plague

Almost immediately a feeling descended on me that, despite the complicated crowd scenes involved, I would like to make some kind of comic about the dancing plague. It popped into my head that there was a soldering iron in my parents’ garage that I had used as a child to burn the image of a kestrel into a piece of wood in an effort to make a placemat. Now for some reason I felt compelled to retrieve that soldering iron.

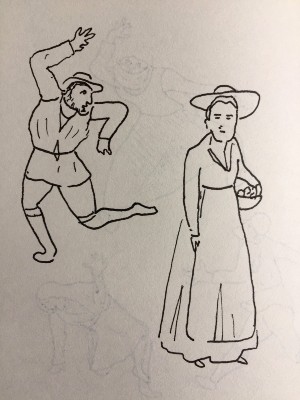

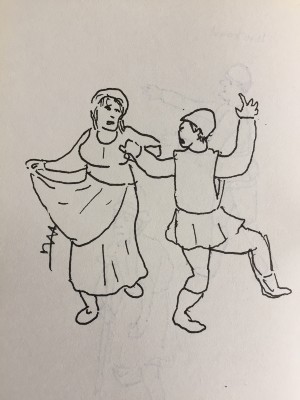

The first thing I did was to find out a bit about the period of time the dancing plague took place in. I needed to find some kind of visual language and points of reference for the comic.

Bruegel lived in the period shortly after the 1518 dancing plague, so this was a very good start. His paintings and drawings of peasants were very helpful in beginning to figure out what ordinary people might have worn at the time. Helpfully, Bruegel had also done some drawings of a dancing outbreak.

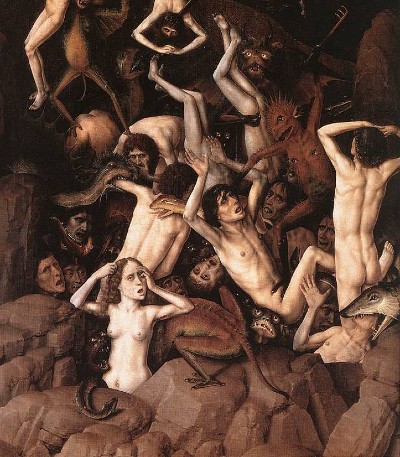

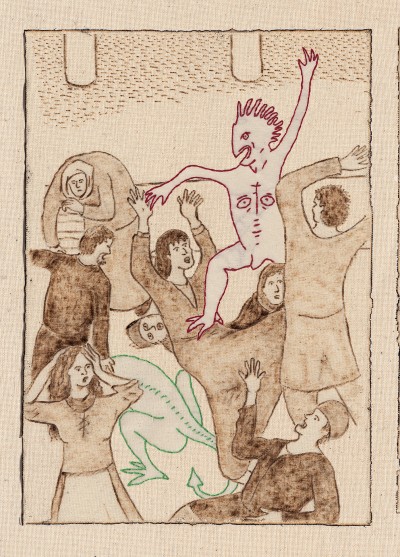

The Fall of the Damned, 1470 by Dirk Bouts, sketch, tracing and finished panel it inspired in The Dancing Plague

After I’d experimented a few times with the soldering iron I had retrieved from my parents’ garage, I invested in a ‘proper’ pyrography tool. This is basically the same as a soldering iron, only it has several attachments (most of them useless) and a temperature setting. The only three really useful attachments were the standard fat line, a fine line and a flat attachment. I soon found that the flat attachments could be used to make tonal areas in my artwork and the temperature setting could be used to produce darker or lighter tones. That said, these pyrography tools were extremely unpredictable and I was never quite sure what kind of line they would produce. It seemed to depend on their mood. I never once during the drawing of the book felt like I’d really mastered their operation, but this kept me interested.

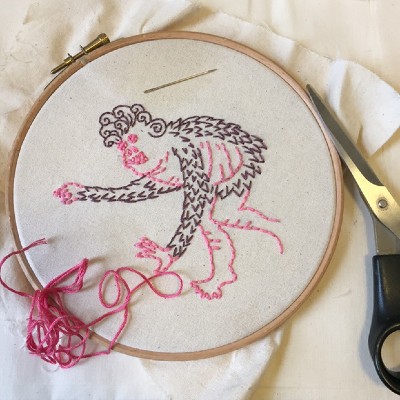

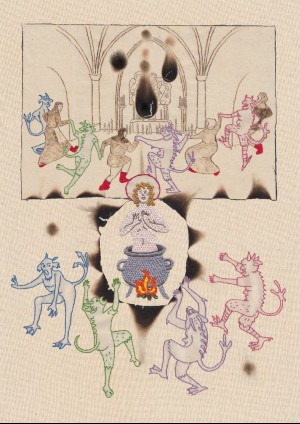

Alongside the pyrography I used embroidery to create the mystical visions that protagonist Mary experiences. Those familiar with my work will know that I’ve used this medium before in The Black Project and Threadbare. In this work I wanted to use the embroidery sparingly and in a way that would introduce vivid colourful moments into the story. This was a lot of fun. There is literally nothing more pleasing than the prospect of choosing the most garish colour in your thread collection to embroider a demon with.

Researching demons in medieval art was also a great deal of fun, they range from the quite sweet to the completely terrifying. Hieronymus Bosch was also a near contemporary of the dancing plague (he died in 1516) and, along with Bruegel, he was the artist who most informed the work. I hoped to capture a small amount of the visceral oddness, the hallucinatory strangeness of ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’.

Bosch’s ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’

Once I had got started, I went to the V&A and did some sketches from medieval tapestries and manuscripts. By 1518, the Renaissance was already underway, but the ordinary people of the period would not have had access to the latest artworks, and their visual language would be dominated by medieval art, so particularly for the visions Mary experiences, I drew from the art of a slightly earlier period. In the end I became good at inventing demons, mixing, matching and improvising from various bits and pieces of features I’d spotted in medieval art.

As well as researching medieval visual art, I did a good deal of research into the dancing plague and into the lives and values of the people who lived at the time. I would recommend the book A Time To Dance A Time to Die by John Waller, which gives a good overview of the 1518 outbreak and speculates on its causes.

I had help form Professor Anthony Bale of Birkbeck, University of London who wrote the foreword to the book. I had several meetings with him to make sure the details were as accurate as possible and the story was as representative as it could be of the worldview of the people who were alive at the time.

For the central character of Mary, I researched female medieval mysticism. The medieval period was full of such mystics, like Hildegard of Bingen and Julian of Norwich. They often led precarious lives walking a tightrope between being revered as holy or condemned as a heretic or witch. Usually it was a man, such as a Bishop who would be making that judgement, and often they would change their minds. Women that were considered holy would often be made Anchoresses, which meant that they would be bricked up in a cell to devote the rest of their lives to Holy contemplation.

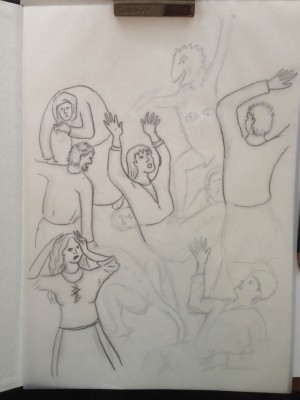

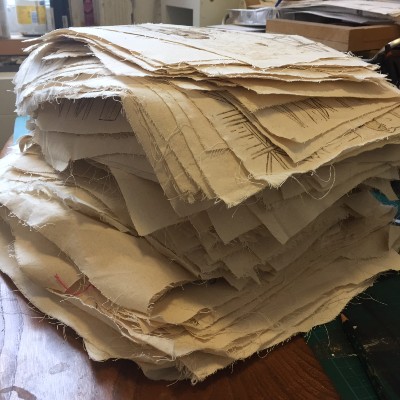

Sketchbook pages

The mystics I chose to base my character on were Christina the Astonishing and Margery Kempe. Christina the Astonishing could levitate, sit in an oven without burning, and stay underwater for days at a time. Margery Kempe on the other hand didn’t have any superpowers but was more of a rebel and an eccentric. She was a middle class business woman, mother of fourteen children who pronounced herself holy and travelled around delighting and irritating people with her divinely inspired pronouncements and constant crying and wailing at any mention of Christ’s passion. These crying fits would last for hours or even days and made her unpopular with fellow pilgrims who travelled with her on various pilgrimages. Anthony Bale is a leading expert on Margery Kempe so I was able to get some valuable insight into her as a character. I would urge everyone to read The Book of Margery Kempe, which is the first autobiography written in the English language.

So much for the starting point and research. What followed was almost three years of intense burning, stitching and photoshopping. I worked in A2 size, most of the four panel pages being composed of A4 panels. This was a decision that certainly didn’t help the project progress swiftly. I should say at this point that I managed to get a grant from Arts Council England to do this project, which really helped me to devote the time required to complete it. I’d certainly encourage anyone wanting to create a graphic novel to give that a go.

People often ask for advice about how to make a graphic novel, my advice is to dive in, get obsessed with it, and quickly mire yourself in a situation where the only hope of escape is to finish it. Another bit of advice is don’t jump into another graphic novel straight away once you’re finished. People often ask what I’m working on next as soon as a book is finished, and the honest answer is that I’m recovering! Having said that small press comics and zines are a great way to get the ball rolling again. I come from a background of doing short self-published work, and this is what I always return to between graphic novels in order to experiment, have fun and get excited about comics again.

For more on the work of Gareth Brookes visit his website here and follow him on Twitter here and Instagram here. You can visit his online store here.

Gareth’s Patreon can be found here.

Article by Gareth Brookes

Fascinating and obsessive project. Thanks for this.

[…] combination of “burning, stitching, and Photoshopping.” (I recommend this wonderful post about the process of making the book.) Does what comics do at their best. A perfect blend of materials and story. †This interview is […]