ELCAF FORTNIGHT!

A drawing of a person is not a person. It might be recognisable as a representation of a person, but the complex systems of tissue and bone and all that gooey stuff that make up a human body have been broken down into lines, shapes or other marks. Comics are a broad enough church to accommodate styles from hyper-detailed photorealism to the totally impressionistic, but neither is a 1:1 depiction of reality as most of us experience it. A face can be as simple as a circle with two dots for eyes. A body can be abstracted to a stick figure. Tsemberlidis and Lando, the enigmatic artists behind Decadence Comics, do more breaking down of bodies than most: in their contrasting-yet-complementary drawing styles, their themes, and the stories they tell.

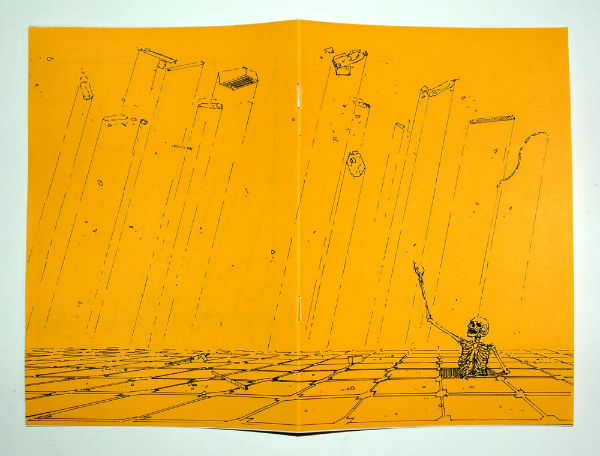

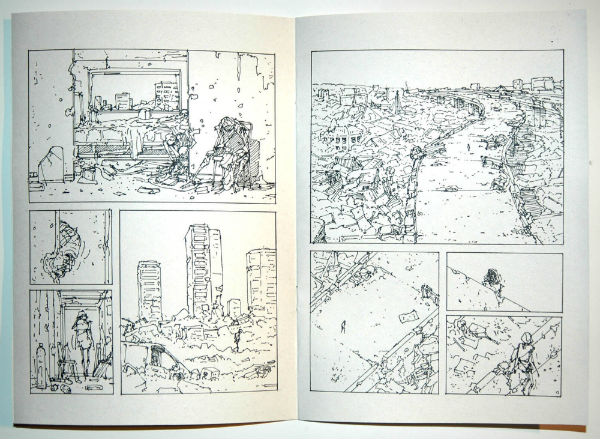

In Lando’s 2014 mini Anthropozine (above images), we follow an emaciated figure who falls prey to the way the artist’s thin, sketchy ink lines (comparable to the likes of Julia Gfrörer as well as the Metal Hurlant masters the imprint pledges allegiance to) represent space and bodies. Stumbling through a post-apocalyptic wasteland, the character happens upon an almost-intact building, and wanders straight into the atrium…not realising it’s flooded. They immediately sink below the surface and drown, presumably to decay further into the skeleton on the comic’s cover. The character’s mistake is understandable, because it’s one we make as readers. Since the inside of the building is so lightly rendered, with beams of light coming through the holes in the ceiling represented by similarly thin lines, it’s hard to tell where the floor ends and where the water begins.

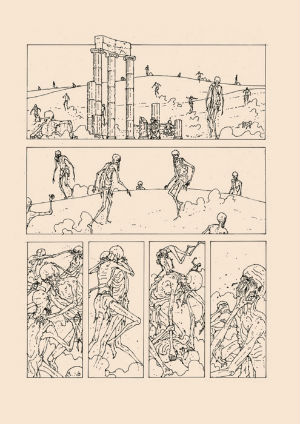

Unfortunate ends for skeletal figures and the horrifying decay — abstraction and breaking down in a more corporeal sense — of the human body is a recurrent image through Lando’s work, as collected in the book Gardens of Glass (published by Breakdown Press, appropriately enough). In the opening story ‘Olympic Games’ (right), teams of futuristic soldiers do battle across a desert landscape. The survivor is elevated on a floating platform patterned after Ancient Greek architecture and sculpture, the pantheon of gods trumpeting their arrival in the heavens above. Those less fortunate are swallowed by the sands, to emerge as zombified impediments to future contenders, their muscles atrophied, jaws collapsed and flaps of torn skin dangling from their necks. It’s pretty gnarly.

Unfortunate ends for skeletal figures and the horrifying decay — abstraction and breaking down in a more corporeal sense — of the human body is a recurrent image through Lando’s work, as collected in the book Gardens of Glass (published by Breakdown Press, appropriately enough). In the opening story ‘Olympic Games’ (right), teams of futuristic soldiers do battle across a desert landscape. The survivor is elevated on a floating platform patterned after Ancient Greek architecture and sculpture, the pantheon of gods trumpeting their arrival in the heavens above. Those less fortunate are swallowed by the sands, to emerge as zombified impediments to future contenders, their muscles atrophied, jaws collapsed and flaps of torn skin dangling from their necks. It’s pretty gnarly.

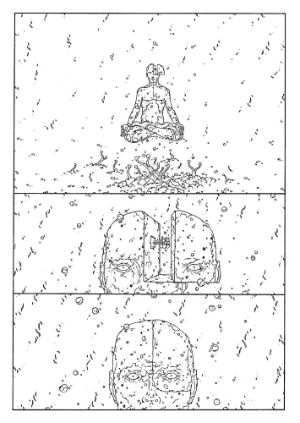

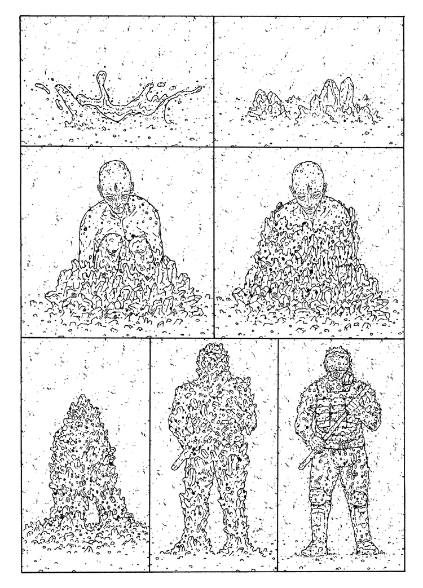

Physical forms fare about as well in Tsemberlidis’s work, collated in the complementary volume Picnoleptic Inertia (below). His linework is thicker, more consistent and sure than Lando’s gestural drawings, and his attention to detail comes through most strikingly with all the pointillist “noise” that covers the characters, landscapes and panels of his stories. Everything is coated in flakes, spots of dirt, suggestions of toxicity. Nothing looks clean. Everything looks like it’s rotting. I feel a bit grubby reading these strips, truthfully. It makes me itchy the way watching wildlife shows about bugs did as a kid.

However, while the obliteration of the human form is also a motif in Tsemberlidis’s stories, unlike in Lando’s work, it’s (mostly) treated as a positive thing. Physical forms wither and dissolve, or are otherwise destroyed, in Lando’s comics — all the easier when they are constructed of shaky, thin ink lines — while Tsemberlidis does away with his more solid shells to an almost entirely abstract spiritual rebirth. His stories hint at a sort of transcendence-truth-destruction, a hallucogenic shedding of physical form which is as beautiful as it is violent. “Cyborg M83” is full of imagery of evolution, birth and death, with animals bursting forth from the skulls of other creatures, a synthetic being in the process of being built, and a dead soldier re-entering a cosmic womb to be reborn.

Both artists work mainly without words (only one story in the Lando collection includes speech bubbles) and their strips are often abstract. Tsemberlidis’s stories are entirely absent of conventional narratives, as are some of Lando’s; you could call this the “breaking down” of comic storytelling into something more avant-garde, if you were so inclined. In his Untranslatable series of minicomics, the latter uses speech but intentionally renders it unintelligible, the bubbles filled with runic symbols and graffiti-inspired nonsense language meant to represent the speech of extraterrestrial beings.

Both artists work mainly without words (only one story in the Lando collection includes speech bubbles) and their strips are often abstract. Tsemberlidis’s stories are entirely absent of conventional narratives, as are some of Lando’s; you could call this the “breaking down” of comic storytelling into something more avant-garde, if you were so inclined. In his Untranslatable series of minicomics, the latter uses speech but intentionally renders it unintelligible, the bubbles filled with runic symbols and graffiti-inspired nonsense language meant to represent the speech of extraterrestrial beings.

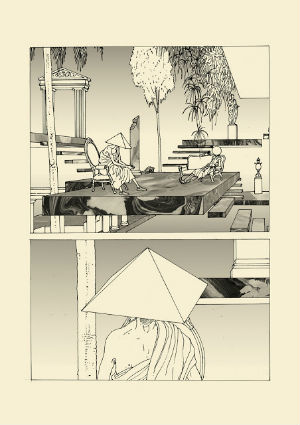

The comparisons to J.G. Ballard and David Cronenberg on the blurbs of these collections and in Decadence literature seems less like an accurate comparison, and more of a way to differentiate these artist’s work from, say, the mainstream sci-fi books that spring up every month at the likes of Image. This is something weirder, more radical, more concerned with themes of human obliteration. This is true in allegorical as well as literal terms, too, as there is undoubtedly a lot of politics in these weird-ass comic books. ‘Olympic Games’ was produced as London was holding the quadriennial event, and its deeply cynical view — where one is heralded above all overs, yet every contender appears to be risking their lives for the entertainment of a ruling class — can’t help but be read as bitterness towards the ruling government of the time. In ‘Pyramid Scheme’ (below left), a man is oblivious to the collapse of the floating platform he, his partner and child live on, wrapped up in the process of his head shifting from humanoid to polygonal and crystalline, and back again. That’s some real male narcissism right there.

In both books, imagery reminiscent of conflicts in the Middle East recur. In the Tsemberlidis stories ‘Epicurean Paradox’ and ‘Upheaval’ there are scenes of civil unrest that appear ripped from 24 hour rolling news, of heavily-armoured police violently attacking protesters. Another story is named for ‘MK Ultra’, the CIA mind control experiments that targeted prisoners, college students and other innocent people. So we have four ways that Decadence Comics survey the “breaking down” of people: from the physical form into ink drawings; from ink drawings into corpses, skeletons, emaciated figures or beings without physical form; the loss of language and conventional stories along with those bodies; and finally the way that the state (or other unreasonably powerful groups, from countries to armed forces to men) suppresses, degradates or otherwise attempts to control its citizens and their bodies.

In both books, imagery reminiscent of conflicts in the Middle East recur. In the Tsemberlidis stories ‘Epicurean Paradox’ and ‘Upheaval’ there are scenes of civil unrest that appear ripped from 24 hour rolling news, of heavily-armoured police violently attacking protesters. Another story is named for ‘MK Ultra’, the CIA mind control experiments that targeted prisoners, college students and other innocent people. So we have four ways that Decadence Comics survey the “breaking down” of people: from the physical form into ink drawings; from ink drawings into corpses, skeletons, emaciated figures or beings without physical form; the loss of language and conventional stories along with those bodies; and finally the way that the state (or other unreasonably powerful groups, from countries to armed forces to men) suppresses, degradates or otherwise attempts to control its citizens and their bodies.

The mononymous, pseudonyms pair of artists — who met studying animation and since started Decadence, first to publish their own work and then of other artists whose styles and thematic interests chime with their own — cite a laundry list of influences on their work, from European comic masters like Enki Bilal, Philippe Druillet, and Moebius, to manga artists such as Katushiro Otomo and Yoshihisa Tagami. Yet in the particular way styles, views on the abstraction of human bodies and themes that stop their work from falling into the current shallow glut of “ugly” comics made primarily by edgy male creators combine, Decadence and their focus on the abstraction of bodies is a genre of comic books unto themselves.

Decadence will be exhibiting at ELCAF. For more on their work visit their site and shop here and follow them on Twitter here. You can also buy their Breakdown Press collections Gardens of Glass and Picnoleptic Inertia here.

Catch up on all our ELCAF Fortnight articles to date here. ELCAF runs from June 22nd-24th. Full details on the ELCAF site here and you can also follow the festival on Twitter here.

[…] Broken Frontier profiles Decadence Comics, the small press publisher behind the work of Lando and Stathis […]