Phillip K. Dick once said “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” But, ironically enough, the paranoid sci-fi author never fully believed this saying, and dismissed it as insufficient. For, he reasoned, isn’t our reality shaped by the societal forces around us, which in turn are fuelled by subjective principles and agendas? Isn’t “truth” simply what the majority agrees on? In an era of disinformation and conspiracy theories, that’s a scary thought, which the hot new Image series The Department of Truth literalises. Here the more people believe in a conspiracy theory – no matter how vile or nonsensical – the more “real” it becomes.

Cole Turner, a new recruit to the “agency” that monitors such conspiracy theories and our audience surrogate, describes it as a “Tulpa” event, a mystical term for something metaphysically manifested out of thoughtforms. Such spiritualism usually points towards benevolent “imaginary friends,” but conspiracy theories are rarely so pleasant. Rather they present disturbing delusions of secret cabals and global agendas, frequently rooted in anti-Semitism and unhinged ideologies. James Tynion IV, writer of The Department of Truth, makes it explicitly clear how dangerous such conspiracies and their viral spread can be, and why its imperative the Department shut them down before humanity’s worst fears and stereotypes are made true by believing in them.

The Department of Truth therefore becomes a mixture of The X-Files and an E.C. Horror anthology, each issue focusing on a different conspiracy the Department must cut down. Yet although it heavily condones this dangerous thinking, The Department of Truth is more nuanced than simply a shutdown of the conspirators, peeking into their headspace as to why they believe such things. The third chapter particularly stands out, revolving around a mother whose child died in a school shooting but is accused of being a “crisis actor.” Tynion not only depicts the inexpressible pain of being told your grief is “fake,” but the more twisted attitude of wanting to agree with them. After all, this conspiracy is the mother’s last connection to her son, and no matter how tenuous or what it implies, it’s a welcome alternative when her son is still alive.

The Department of Truth understands conspiracy theories, is what I’m saying, containing sociological observations of recurring patterns in conspiracies (drawing parallels between the ‘80s Satanic Panic and the modern “PizzaGate”) and how people fall into them. Cole himself was embroiled in a traumatic experience while young, and The Department of Truth displays how thoughts can return to them like picking at a scab, especially since Cole now knows that even thinking about the Star-Faced Man who haunted him grants it more power (the worst way to stop thinking about something is being told to do so).

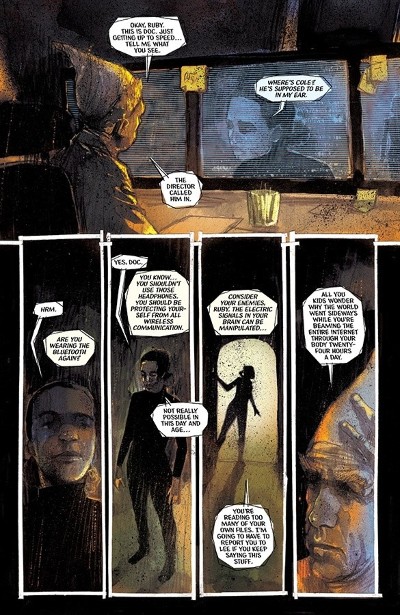

Somehow, The Department of Truth is also pretty funny. Tynion treats the aforementioned subject matter with sensitivity, but (aside from a little verbose first issue) the series does not feel weighted, with genuine rapport between Cole and his fellow Department Agents. This first volume provides only minor introduces to them, but their confident portrayals keep you engaged and grounded amidst the grander ideas, as does Cole’s relationship with his husband. Tynion is not so self-serious he cannot have fun with this premise – featuring “lizard people” and “tin-foil hats” and jokes about “needing to go kill Santa Claus again” – he simply doesn’t minimise the genuine harms these conspiracy theories can create.

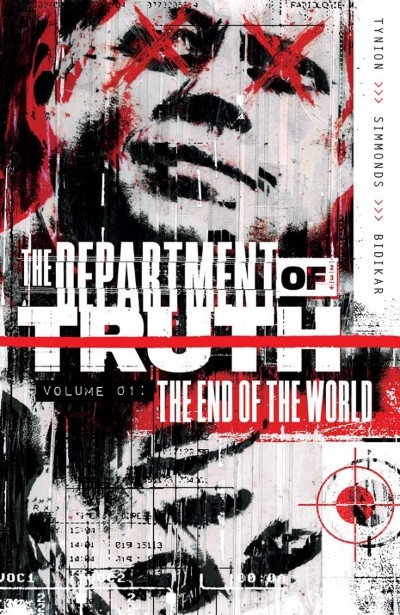

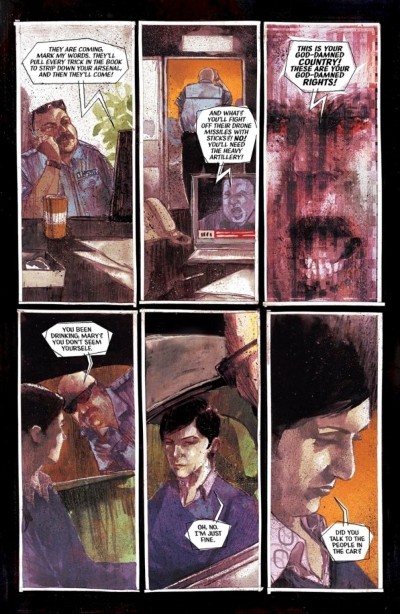

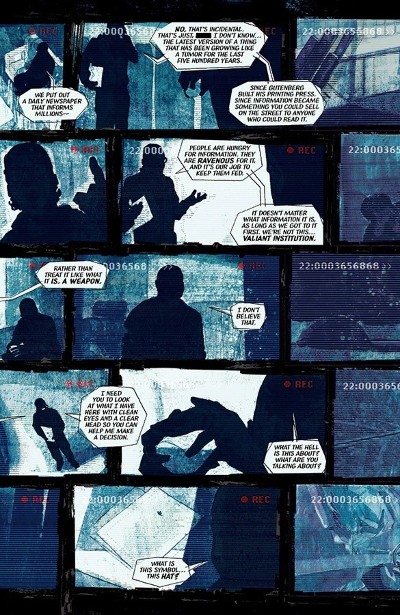

This disturbing atmosphere is perfectly conjured by the artwork of Martin Simmonds, whose phantasmagorical and scratchy illusions perfectly emulate the disorientating dreamlike aura of the series, like a series of polaroid pictures that have been exposed, distorting and traced over. At certain points, Simmonds leans towards the bleeding photographic watercolours of Alex Maleev, before the shifting reality turns towards the surrealism of Bill Sienkiewicz and Dave McKean. Simmonds doesn’t radically change art-styles, but rather allows for a fluid, sometimes terrifying, expressionism in his illustrations. The same is true for Aditya Bidikar’s lettering, who usually employs an official “case file” type-set for the actual letters, but contains them in boxy word-balloons that do not quite fit within their lines. The ambiguous collage-art style goes down to what is being said.

The Department of Truth combines all these elements effortlessly, functioning well both as it is read, but also – much like having a detailed conspiracy corkboard – when you step back and appreciate the “big picture.” The compositions in chapter 4, which view conversations through the reel of a surveillance feed, or a transcendent two-page spread following a “Flat Earthers” conference in chapter 1 are just some of the highlights. The Department of Truth is a hypnotic masterpiece in almost every aspect, tackling relevant themes alongside strong human pathos, addressing who gets to “decide” what reality is and how such “beliefs” are spread. The Department of Truth is still ongoing, making this first volume a perfect place to start. And as in all good conspiracies, its the way it brings all these various elements together that’s the most satisfying.

James Tynion IV (W), Martin Simmonds (A), Aditya Bidikar (L), Dylan Todd (D) • Image Comics, $9.99

Review by Bruno Savill de Jong