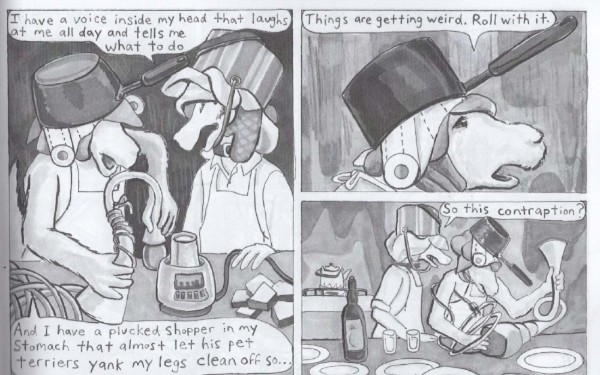

At about the midway point in Scott Finch’s The Domesticated Afterlife, one character advises another: ‘Things are getting weird. Roll with it.’ He’s right, of course, but he’s understating, and this is advice that could be given at any point in this story. The landscape of this narrative is at turns Borgesian labyrinth, Kafkaesque drama or biblical purgatory, and it can’t help but twist itself into something sinister. It could be summed up as dreamlike or surreal, but this is a world populated by animals and so slips easily into the space of a fable, with various visual elements or plot points offering themselves up as symbolic of some deeper truth, or a critique of some aspect of our contemporary lived experience.

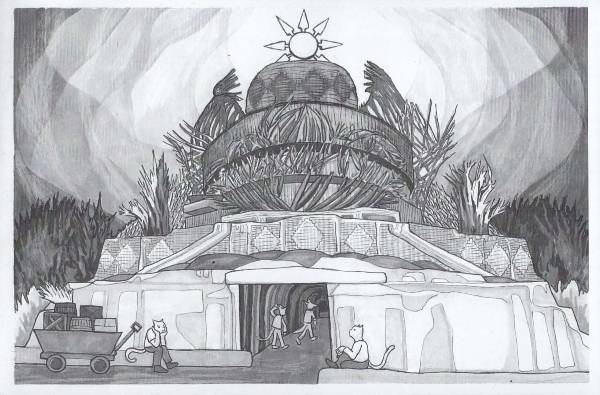

We follow a fox and a dog as they leave their decimated, resource-sapped forest home to enter an enclosed, domesticated world. They become anthropomorphised in the process and are quickly habituated within the routines and soul-destroying drudgery of an urban, consumerist metropolis. They queue for food, perform menial jobs, go to sleep and get up and go back to their menial jobs. This society has a hierarchical structure, but it’s the inverse of what we’d expect: canines seem to be at the bottom of the ladder, with cats somewhere in the middle and birds – specifically chickens – on top, pampered and spoiled into a satiated stupor. Domestication is socialisation, a Rousseauian disturbing of nature, of natural hierarchies, natural instincts and natural orders.

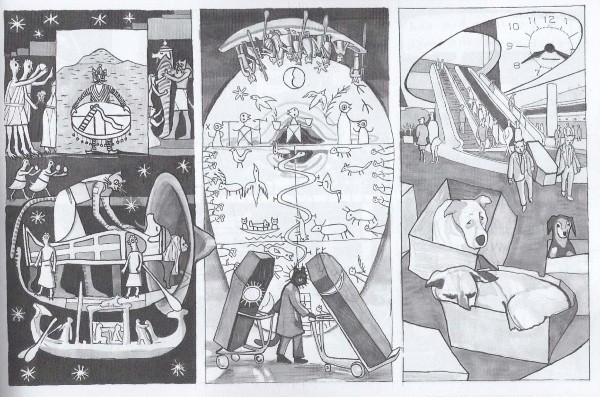

The Domesticated Afterlife is certainly complex, but there is a narrative thread here. The fox and the dog wrangle a job at Sun Corp, the local, omnipresent consumer paradise, and things take a dramatic turn after a violent incident with a rebellious customer. But the draw of this book is that there is so much else going on. Beyond a resurfacing critique of everyday consumer culture, we are quickly plunged deep into more esoteric things and pulled through layers of symbolism and allegory as the plot progresses: Osiris’s all-seeing eye…Noah’s ark…infinite spirals…the golden section…and other stuff I still need to look up.

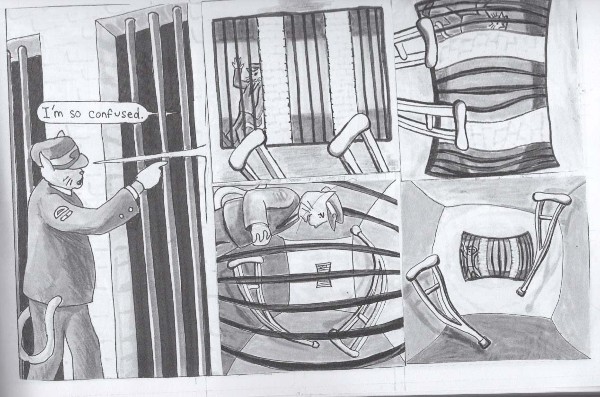

The book’s 281 pages are split into titled chapters, and this allows you to break your reading into chunks. I found it easy to do this over the course of a week, to pick up the threads of the story and get back into the headspace of the world. It seems to work at its best when it gives in to the absurd, internal logic of the world Finch has created. But this logic is occasionally made more sensible and there are moments of more straightforward exposition, as if Finch decided on where the plot was going and needed these details to get there. Names of characters are introduced later, for example, at the point when a growing cast needs to refer to one another.

The artwork is rendered in muted grey tones and Finch’s process has a visible presence. Sometimes initial pencil workings breach the borders of completed panels, the occasional collaged piece of paper has been used to revise or correct a panel. It also feels like a work that Finch has constructed slowly over some time, gradually pulling together images and meaning panel by panel and allowing each completed page to suggest the next. The result is that, even though the details of the story can at times become unwieldy or escaping, information seems to be there, waiting to be found in the rich detail of the panels – the work draws you in to explore, rather than push you out.

This is an ambitious and impressive read and one I’ll be returning to in future to continue to unpack. It is a recommended experience.

Scott Finch (W/A) • Self-published, $18.00

Read new chapters on SOLRAD here

Review by Jon Aye