“The world’s most destructive oil operation.” That is the description National Geographic went with for a 2019 profile of Alberta’s oil sands region north of Fort McMurray. A distressing report on the world’s third-largest oil reserves, it painted a picture that was radically at odds with Canada’s statements on climate change abroad. Conversations about this industry have always been difficult, given not just the sheer amount of capital involved, and what that means for companies and employees working on these oil fields, but because of the larger implications related to energy and the environment.

A simple Google search yields all kinds of contradictory information about this part of the world. There are supposed exposés about the boom town’s debauchery and excessive living, for instance, as well as lengthy studies on substance abuse and crime that often come into play whenever large sums of money and a floating, global workforce collide.

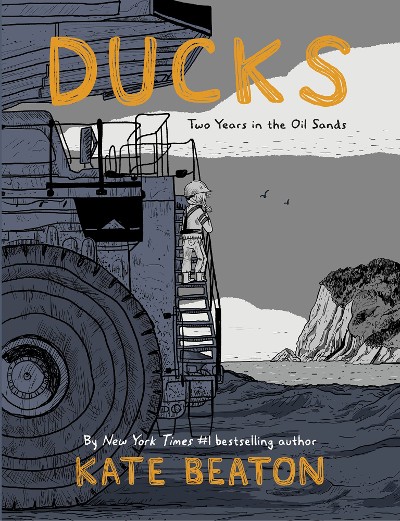

On the surface, then, it seems like the type of subject completely at odds with what one would expect Kate Beaton to focus on. Those familiar with the Canadian artist’s hilarious debut Hark! A Vagrant, will vividly recall her skewering of historical and literary figures, from Sherlock Holmes and the Brontë sisters to Napoléon Bonaparte and Nancy Drew. Where are the witty non-sequiturs and laugh-out-loud comments here, one might ask. The ghost of that astute commentator appears quickly though, once one gets used to the change of setting and pace. Moving away from a comic panel allows Beaton the luxury of getting under the skin of characters who populate this autobiographical, deeply personal narrative.

Beaton worked at the oil sands over a decade and a half ago, using a five-part comic in 2014 to put forth her reasons. For young Canadians growing up in small communities — like she did in Mabou, Cape Breton — there were limited employment options and paying off student loans often depended upon them moving out to larger cities for opportunities. The lucrative oil sands must have seemed as good a place as any, until she arrived to confront the shock of isolation, the shadows of behemoths under which extraction took place, and the presence of 50 male workers for every female one. It is ironic, with hindsight, that the two-year stint may have helped pay off her loans but ended up leaving her with emotional scars that extracted a much heavier cost.

What Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands sets out to do, from the outset, is document an uncoloured perspective entirely her own, as a counter to the numerous other reports published by people who simply hadn’t spent as much time there as she did. It is the setting straight of a record, albeit one among potentially a million others, and she speaks of how impossible it is to chronicle using just one or two stories. Her format of choice, then, is to allow as many events and instances as she can to coalesce into the semblance of a larger picture. What emerges is a sense of how easy it is for an outsider to categorise an industry or place without taking into the account its human impact.

The industry affects the Alberta boreal forest and ground water, weakens international commitments such as the Kyoto Protocol, and constantly threatens a fragile ecosystem. What criticism of every aspect of oil production often fails to account for, unfortunately, is how the area’s indigenous groups are often compelled to embrace the only economic options that simultaneously risk their society and culture. This is the kind of reportage Beaton brings to the issue, in much the same way that cartoonist and journalist Joe Sacco explored conflicts in the subarctic Canadian Northwest Territories not long ago with his own memoir, Paying the Land.

“The oil sands operate on stolen lands,” writes Beaton in her Afterword. She doesn’t shy away from these painful truths, while making sure to lay bare the great distance between how an exploitative industry generates wealth for a chosen few, while debilitating the lives of those it relies upon to extract that wealth. One may not find the Kate Beaton one is accustomed to. There is a more accomplished artist here though, and a writer armed with a singular ability that often separates good storytelling from the great: empathy.

Kate Beaton (W/A) • Drawn & Quarterly/Jonathan Cape $39.95/£25.00

Buy online here from D+Q and here from Cape

Review by Lindsay Pereira