Eartha is not so much a tale of two cities, as of two halves of the same paradox.

The soft edges and subtle tones of Cathy Malkasian’s artwork and hand-drawn design seem to be an echo of her eponymous heroine; round in face and figure and more than double the size of the other inhabitants of her strange home, Eartha is portrayed from the beginning as a benevolent and well-loved figure in her homeland, the ‘Fyord’. She’s not particularly bright, but perpetually well meaning and earnest. As naturally bigger and stronger than her fellow Fyordians, most of whom seem to be perpetually drunk, she has an integral role in their little society – performing the essential task of carrying inert and inebriated characters home from the pub.

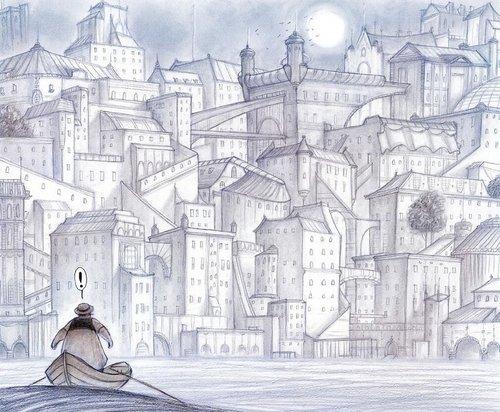

There’s a sense of dream logic to Eartha’s homeland; guide dogs that literally give their owners spoken directions, hallucinatory plums, ‘shadow masonry’. A gentler dream logic than that of the Fyord’s chief import – literal incarnations of dreams which come direct from the minds of citizens of the mysterious metropolis. These dreams tend to be presented as the basest or silliest fears and desires of those far off denizens, but at the beginning of the book they are running out. This catalyst for Eartha’s anxiety sends her on an adventure to the other place across the water where the dreams come from. And from there, it starts to get seriously weird.

With comics as with films, the length of time it takes to produce the work precludes any really up-to-date social commentary, and it’s hard to decipher the real target (if there is one) of the dystopian scene Eartha finds in The City. Because of the focus on consumption of ‘news’ and social control it feels like this ought to be a biting political satire, but this graphic novel is not really about those things, it’s about dreams and stories.

Where the Fyord has been accustomed to receiving both their vocation and entertainment in the form of projections of inner turmoil from The City while The City ignored the world outside its walls, the dreams have apparently now dried up because The City has become outward looking. This comparison of rural with urban, simple with complex, drunk and jovial with sugar-fed and introverted is central to the narrative but pleasingly fractured. Individuals in both locations remain messy bundles of contradictions in their own right, when they are allowed to do so. It’s just that that freedom in both cases relies on a complexity of stimulus that has been stifled.

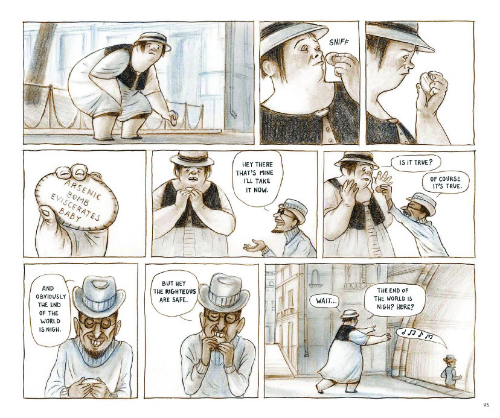

When Eartha arrives she is greeted by an economy based entirely on the desire to consume news biscuits. Biscuits yes. With news on them. News from outside the city. Always bad news. The people are so preoccupied with selling all their possessions (including their talking pets and parents’ homes) in order to obtain said knowledge and feel worldly and brave. Okay, the real world parallels here are not really obscure, and the controllers of the biscuits (and therefore the people) are as vague in their ideology and as back-stabbing in their power grabs as the best Doctor Who villains. Levels of exposition here are as clunky as the worst Doctor Who dynamic set-up though, and the dramatic denouement is as frustratingly final, if at least not simple.

I wasn’t sure where the Doctor Who comparison came from there, but it makes a lot of sense. Protagonist comes in from outside, bemoans the status quo, coincidentally befriends the resistance, handily solves all the planet’s problems in time for tea. I should stress that I haven’t actually seen any classic Who. This is a Moffat hat doff.

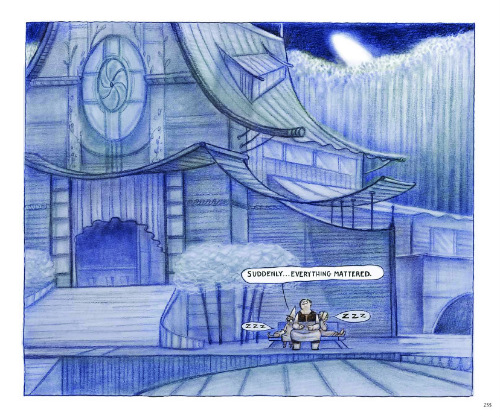

But if the logic here is really dream logic, plot shouldn’t be the first concern. The pleasure of Eartha is in the tone of muted, grumpy idealism and gently surreal tangents. As Eartha’s friend Maybelle says in the beginning “our life’s about being together, and finding joy in the things we can’t explain.” If Malkasian had stayed a little truer to this ethos, and put in more tangents and less explanation, the tone might have been even more successful. What does work, is the world she has created here: soft, swooping vistas seen from a variety of perspectives and frames as rich as the diverse and eccentric cast of characters, and epitomising the message of the small and local and true being truly the biggest things.

I read Eartha in the digital format, but I understand it’s well worth getting your hands on a physical copy, to do justice to the artwork and formatting. Both can be purchased here, or from your local friendly comic retailer.

Cathy Malkasian (W/A) • Fantagraphics Books, $29.99

[…] favorite books, Simon Moreton’s PLANS WE MADE. *Jenny Robins reviews Cathy Malkasian’s EARTHA, and says it contains “soft, swooping vistas seen from a variety of perspectives and frames […]