Nonsense is an underrated tradition in literature, now relegated to dusty shelves alongside the verse of Edward Lear and lesser-known works by Lewis Carroll. Almost two decades after he passed away though, there is still a compelling argument to be made for why Edward St. John Gorey’s illustrated work in this genre ought to be given more attention by writers, illustrators, and readers of graphic novels.

Nonsense is an underrated tradition in literature, now relegated to dusty shelves alongside the verse of Edward Lear and lesser-known works by Lewis Carroll. Almost two decades after he passed away though, there is still a compelling argument to be made for why Edward St. John Gorey’s illustrated work in this genre ought to be given more attention by writers, illustrators, and readers of graphic novels.

Let’s begin with the art itself — precise, economical, and always evocative, populated by creatures from a rich imagination of the sort that anyone familiar with Robert Crumb, Charles Burns or Kate Beaton would delight in. Then there’s the writing, reflecting a view of the world that is sometimes gruesome but almost always amusing. Taken as a whole, his visuals and language reflect his own influences from Michelangelo and Vermeer to Francis Bacon, Jane Austen, René Goscinny, and Albert Uderzo.

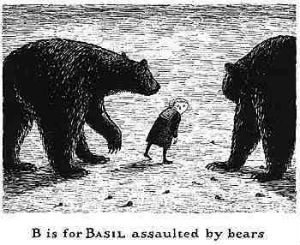

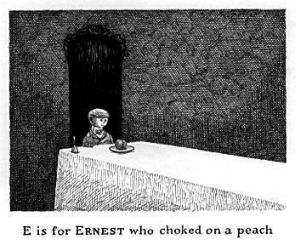

Consider, for example, The Gashlycrumb Tinies (below), possibly responsible for changing the way thousands of children look at the alphabet since its publication in 1963. From ‘A is for Amy who fell down the stairs’ and ‘B is for Basil assaulted by bears’ to ‘Z is for Zillah who drank too much gin’, it still has the potential to raise a smirk in anyone receptive enough to recognise the validity of Gorey’s unique worldview. The Tinies appear along with other mini-masterpieces such as The Unstrung Harp, The Fatal Lozenge and The Wuggly Ump, in collected volumes like Amphigorey, Amphigorey Too, and Amphigorey Again, punning on the Victorian mode of nonsense called ‘amphigouri’.

A series of disasters befalling children doesn’t sound like amusing reading, but it is a perfect sample of what makes Gorey such a cult figure, attracting anyone who doesn’t subscribe to the conventional. His style continues to have a powerful impact on musicians and filmmakers because what appears, at first glance, to be absurd or merely mocking, eventually reveals a rather deep engagement with big questions about life.

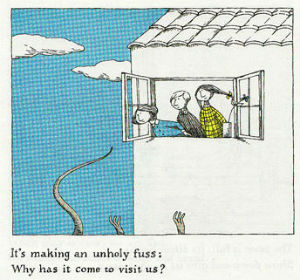

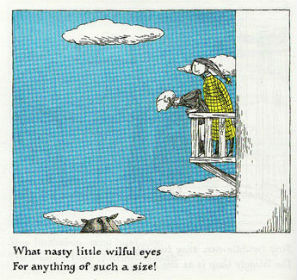

Art from Gorey’s The Wuggly Ump

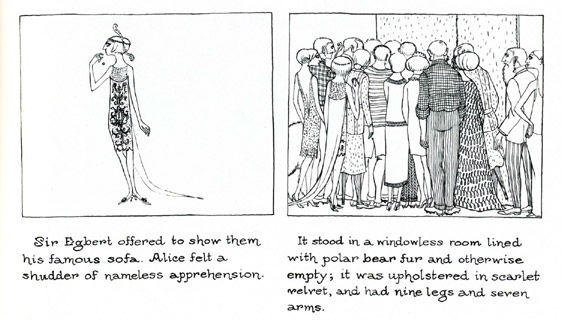

Like all great artists, Gorey’s distinctive approach separated his work from what his contemporaries were doing. To dismiss him as a pen-and-ink illustrator of unsettling Victorian settings is to deny his masterful blend of satire and humour. What would be tasteless in the hands of a lesser artist is saved and elevated by his dry wit. In The Curious Sofa (below), for instance, marketed in 1961 as a ‘pornographic illustrated story about furniture’, anything remotely sexual comes from the overactive imagination of the reader alone, because Gorey’s drawings offer nothing that can be described as erotic.

Amphigorey and Amphigorey Again make great introductions to Gorey’s oeuvre because they bring together not just stunning examples of his most accomplished work, but also rough sketches and unpublished stories (La Malle Saignante) that celebrate his facility over art and language.

For readers who appreciate intellectual curiosity and a powerful imagination, where strange beasts rub shoulders with elegant ladies and cantankerous gentlemen, Edward Gorey transforms the seemingly ordinary into something delightfully strange. Just like the best art always does.

Feature by Lindsay Pereira