Grant Morrison might have had his invitation to Buckingham Palace and Bryan and Mary Talbot might have gatecrashed the literary world by picking up the 2012 Costa Biography Award for Dotter of Her Father’s Eyes, but here in the UK we’re still a long way behind our neighbours across the Channel in terms of the cultural reverence we give to our comickers.

In Paris at the moment, the city’s Musée des arts et métiers – a repository for centuries’ worth of scientific and technological artefacts – is hosting Méchanhumanimal, a wide-ranging exhibition of work by one of the true masters of the comics form, Enki Bilal, who earlier this year also exhibited at the Louvre.

Anglophone readers have had a frustrating time trying to follow Bilal’s career over the decades. English-language editions of his books have drifted in and out of print from a number of publishers and in a number of formats – none of which have ever approached the classy presentation of the French originals.

However, I’ve been so captivated by the worlds he creates, and the striking characters he populates them with, that I’ve still picked up his tomes wherever possible, even if the inadequacy of my French makes reading them a slightly frustrating experience. Still, despite the language barrier, the richness of his work – especially his stunning futuristic cityscapes – epitomises to me all the allure of bandes dessinées and the album format.

The exhibition contains around a hundred original pieces of work dating from the 1970s to the present day, collected under a series of headings that reflect recurring themes in his work: Human passions; Animals, Monsters and hybrids; Conflict; Machine dreams; and The planet. As well as extracts from his BD work and other graphic projects, he has also completed a series of new paintings especially for the exhibition.

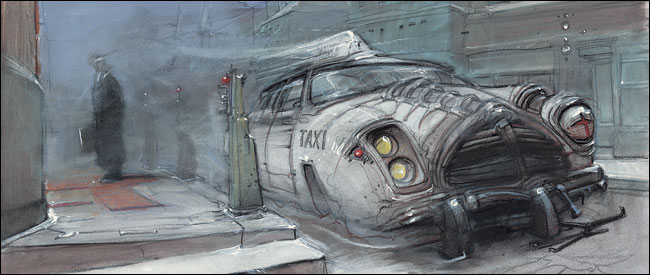

While Bilal’s work is always instantly recognisable, the show highlights the development of his style from the more tradition ink and watercolour of his early work (including the landmark Nikopol trilogy, 1980-92) to the looser, more vibrant pastel and acrylics of the Le Sommeil du monstre tetralogy (1998-2007), which drew on the violent break-up of Yugoslavia, where Bilal was born and spent the first nine years of his life. Finally, we see the altogether more subdued, ‘unplugged’ style of his more recent books – Animal’z and Julia et Roem – which use a delicate blend of oil pencil and pastel on tinted paper.

However, there’s quite a bit more to the exhibition than merely the pages on display. Bilal has also chosen 19 items from the museum’s collection – including a window-cleaning robot, an old X-Ray tube like a Flash Gordon ray-gun and a prototype teleprinter – to illustrate his concept of ‘Méchahumanimalism’: “The life given to machines by Man, inspired by the kingdom of living things”.

His new paintings also touch on the theme; in a similar vein to his Ghosts of the Louvre show earlier in the year, he takes photos of items from the museum’s collection and melds them with his own human figures, as in the image used to promote the exhibition – Méchanhumanimal #04 (Machine for cutting conical gears).

The exhibition also features a very welcome innovation for visually impaired visitors in the form of 3D relief renditions of some of the images, complete with a description in Braille. In addition, a variety of writers, scientists and other thinkers have their say on the issues raised by the exhibition, and there is a nifty 3D recreation of Jill Bioskop’s ‘Script-Walker’ writing device from La Femme Piège (The Woman Trap).

Seeing extracts of comics out of their narrative context can sometimes be a bit unsatisfying, but Bilal imbues each of his images with such creative resonance that you can feel the history and possibilities of the worlds he creates stretching out before and behind them. His work highlights the special power that comics attain by harnessing character and narrative with the infinite possibilities of the visual arts.

Back in 1888, the English critic William Pater reckoned that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music”, for the way it combines its content and form. However, even a flying visit to Méchahumanimal leaves you thinking that in the hands of a master such as Enki Bilal, comics win!

Méchahumanimal runs until 5 January 2014 at Musee des art et metiers, 60 rue Reaumur, Paris 3 (Metro: Arts-et-Metiers or Reaumur-Sebastopol). The exhibition’s French-language website includes further information on the show and the items chosen from the museum’s collection. A book to accompany the exhibition has been published by Casterman, but it had sold out its initial print run during my visit.

***

Image notes:

Lead image: Mécanhumanimal #04, acrylic and pastel on digital print, 2013 (unpublished)

Taxi: Rendez-vous à Paris, page 24 (detail), acrylic and pastel 2006 © Enki Bilal / Casterman, 2013

Landscape: Animal’z, page 75 (detail), oil pencil and pastel on tinted paper, 2009 © Enki Bilal / Casterman, 2013

Though not a fan of his latest works Animal’z & Julia et Roem, I went to Bilal’s previous retrospective in Liége, Belgium and in terms of art, it was a life changer. Nothing can compare to seeing Bilal’s originals in their full glory and the epiphany I got was the same as went to a Giraud retrospective. Comics are art! Cheers!