Moving on from diary comics to fiction, Julie Delporte uses her dazzling, spontaneous art to take us inside the head of a troubled young woman.

Moving on from diary comics to fiction, Julie Delporte uses her dazzling, spontaneous art to take us inside the head of a troubled young woman.

French-born, Montreal-based artist Julie Delporte came to prominence for Anglophone readers as a stylish comics diarist with Journal (Koyama Press).

French-born, Montreal-based artist Julie Delporte came to prominence for Anglophone readers as a stylish comics diarist with Journal (Koyama Press).

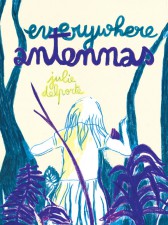

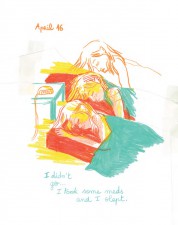

And, at first glance, her new book from Drawn & Quarterly, Everywhere Antennas, could be mistaken for a continuation of that work; the pages have the same distinctive blend of cursive text and spontaneous pencil drawing, and the narrative even takes the form of dated journal entries.

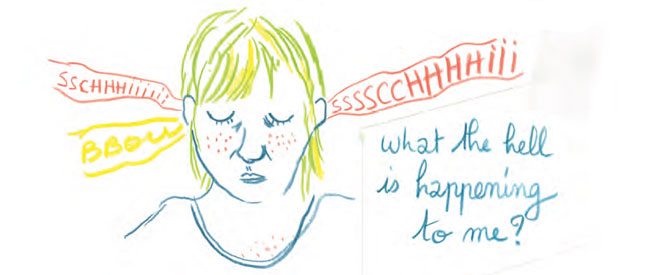

However, we’re gradually drawn into the fictional world of Lily, a young French woman who begins to nurture the idea that her ill health (migraines, hot flushes, insomnia, inability to concentrate) are the result of a heightened sensitivity to the electromagnetic waves given off by the technology at our fingertips.

Taking advantage of a friend’s offer, she heads to a remote cabin in Quebec. Becoming increasingly in touch with her own company and with nature (with some lovely evocation of the sights, smells and sounds of the countryside), Lily finds herself cutting the ties with her old life and facing an uncertain future.

As alluded to above, Delporte’s style follows that of Journal closely, pushing the definition of the comics medium. This isn’t comics in their most common beat-by-beat, panel-by-panel form, but neither is it purely illustrated prose. Instead, it absolutely combines text and graphics to produce a hybrid visual narrative environment.

As alluded to above, Delporte’s style follows that of Journal closely, pushing the definition of the comics medium. This isn’t comics in their most common beat-by-beat, panel-by-panel form, but neither is it purely illustrated prose. Instead, it absolutely combines text and graphics to produce a hybrid visual narrative environment.

As the act of drawing is at the heart of the book, it’s fitting that the reader is made aware of its form. For example, whereas some creators try to hide their ‘workings’, the marks where elements of the pages have been stuck together are left visible in Everywhere Antennas.

Colour is Delporte’s stylistic weapon of choice: both the shifting colours of the text, highlighting the narrator’s fragmented, restless thoughts, and the non-naturalistic, even Fauvist colours used – often to startling effect – in the illustrations.

The first-person nature of the work and the importance of drawing to its protagonist put the nature of the illustration front and centre: the coloured pencils used are even invited back for a bow at the end. Like the water in a fish tank, the bold artwork forms the environment in which Lily and her story exist. Story and form are linked in the inextricable way that defines the best comics.

The first-person nature of the work and the importance of drawing to its protagonist put the nature of the illustration front and centre: the coloured pencils used are even invited back for a bow at the end. Like the water in a fish tank, the bold artwork forms the environment in which Lily and her story exist. Story and form are linked in the inextricable way that defines the best comics.

Of course, the subjectivity of the narrative and Lily’s lack of any evidence-based approach in her self-diagnosis (fuelled, ironically, via podcasts and the internet) invites another, slightly more provocative reading of the book.

On the cusp of meaningful adulthood (she’s in the latter stages of preparing for her teaching exam), is it possible that Lily invokes her illness as part of the much-yakked-about “quarter-life crisis”? Is it part of an unease about modern life and fear of commitment that finds fertile ground in the anti-science paranoiaverse of the internet?

More pointedly, her urge to retreat from the techno-laden modern urban world can be seen in parallel as a retreat from the responsibilities of adult life – a gradual regression back into a child’s summer-holiday world of reading comics at her dad’s cottage, drawing and wanting to look after animals. Even the name of her final destination – Magic Hill Farm – sounds like something a child would create.

More pointedly, her urge to retreat from the techno-laden modern urban world can be seen in parallel as a retreat from the responsibilities of adult life – a gradual regression back into a child’s summer-holiday world of reading comics at her dad’s cottage, drawing and wanting to look after animals. Even the name of her final destination – Magic Hill Farm – sounds like something a child would create.

But although she seemingly ends the book in a place of contentment (and cut off to the point where she doesn’t even know the date any more), one still doesn’t get the sense that Lily has concluded her ongoing but surely doomed quest for “a life without waves”.

Whichever way you choose to read Lily’s experiences, the fact that Julie Delporte’s seemingly simple work offers such a diversity of interpretation is a tribute to the depth of her vision.

Julie Delporte (W/A), Helge Dascher (Translator) • Drawn & Quarterly, $19.95, May 2014