An artist’s personal experiences are often found reflected in their work. This is no different for Brazilian twins Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá, who’ve offered a unique perspective through their art, whether it’s been collaborating on projects such as Casanova with Matt Fraction, Sugarshock for Joss Whedeon, and The Umbrella Academy with rock star Gerard Way, or creating their original graphic novel Daytripper, which won Eisner, Harvey, and Eagle Awards.

Now the twins look to take this trend a step further with their latest graphic novel, Two Brothers, an adaptation of the popular Brazilian novel by author Milton Hatoum. The story revolves around a family living in Manaus, Brazil, which has become fractured due to the intense rivalry between two identical brothers, Omar and Yaqub.

After a violent exchange between the young boys, Yaqub, “the good son,” is sent from his home to live with relatives in Lebanon. When he returns to his hometown five years later, he’s a virtual stranger to his family. Despite their mother’s desperate pleas, a reconciliation between the brothers appears elusive.

Two Brothers, published by Dark Horse Comics, arrived in comic shops on October 14 and is due in bookstores on October 27. Just before heading out on their release tour (which included NYCC), the two brothers, Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon, were kind enough to speak with me over Skype from their studio in Brazil.

Why did you choose to adapt the novel Two Brothers into a graphic version, and what was it about the story that made you feel it fitted your approach to art and storytelling?

Gabriel Bá: The story in Two Brothers is very intense. It’s a powerful tragedy and it was a big challenge for us, because the structure of the book tells a story through memories and people relating memories to the narrator, as well as what he has seen. There was a lot of back and forth and it was a big challenge for us to keep that structure and the style that Milton writes in and also put a visual layer of storytelling in it.

Fábio Moon: I think comics are great for emotional stories, for relationship stories. I think the fact that we can have scenes in silence has an effect on the reader. They are able to look at something they were not supposed to see.

When you exchange words for pictures, you have these silent moments that give the impression that the reader is being let into a secret world. That creates a connection with the reader and the characters. This story had such a complex relationships that if we could pull this off in comics, the readers would be deeply affected and connected to the characters. So we thought it was a good challenge to try to pull off.

Did you speak with author Milton Hatoum at all during the process, or did he leave you to work on your own?

Bá: We were actually invited to do this adaptation by the Brazilian publisher, just for the the fact that we are twins and the story is about twins. It was the initial spark. When we were talking to Milton (we were all guests at a literary festival in Brazil), he was very excited from the get-go.

He knew a little bit about our work and he trusted us to do a good adaptation. But during the process, he didn’t want to get too involved. He gave us total freedom. And we didn’t want to reach out to him all the time to ask about what he meant here and there.

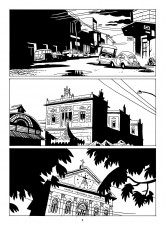

We just talked to him two times during the whole process. One was in the early stages. We went to visit Manaus, the city where the story takes place, to get to know it and to understand the universe of the book. We asked him for advice on places to see, what details we should pay attention to, and he introduced us to some friends who still lived there who could guide us through the city. So it was very important to talk to him to get these pointers.

And then two years later, when we started sketching the characters, we came to him to show him the initial designs. He was crucial to getting the final look of Zana, the mother, because we first pictured her as a more sensual, exotic gypsy kind of woman, and he had a completely different idea of her. She should be more elegant.

He showed us some family pictures of his mother and women of the time who lived in Manaus, and those pictures matched the research we were doing visually. But at first, we didn’t want to accept that was the kind of woman he was writing about. Speaking with him was very important in understanding what was the role of Zana, what she represented and how important she was for the whole book.

But those were really the only two moments we really talked to him. Only when the book was completely done, we sent the whole thing to him. He liked it a lot. He talks about the book better than we do and he loves the work. And it’s great to do panels with him.

Can you tell us a little more about your creative process and how the two of you work together?

Moon: Well, we work here. You see, this is our studio (pointing behind them at two drafting tables facing each other). Those are our tables. So we work here every day in front of each other. Our daily routine is talking to each other about what we’re doing. There’s a lot of dialogue and talking back and forth so we can break down the story – this is going to happen like this, this is where we’re going to turn the page, this is something we can keep and this we can turn into images. So the scriptwriting parts of our collaborations are conversations.

After we work on the script, we have to decide which one of us is going to draw. Our styles have similarities, but they are very different. We try to choose which style fits best for each story. Or we do the opposite: we choose the story that best fits the artwork, which was the case for Two Brothers, because I did the artwork for Daytripper. We knew the next thing we collaborated on, we needed something that my brother was going to draw.

So that was also one of the reasons we agreed to do this adaptation, because we knew it was something he was going to draw. He wanted to draw that world. He wanted to create those characters. But at the same time, we are still working in front of each other. I’m watching over his shoulder and he’s showing the pages to me and we have each other to bounce ideas off and get a reaction and to say “Ah, this could be better”, and “This could work and this is not working, change this angle, change this page, redo this panel”. We are always sharing the work process as we are doing it. But he drew the whole thing after we worked on the script.

And why did you decide to leave the artwork as black and white rather than color it like you did with Daytripper?

Moon: I think there’s this aspect of the story being about the past and all these layers of memories. There are the memories of the characters that talk to the narrator. There are the layers of what the narrator saw. And all of this is woven together in a very fluid way in the novel. And doing that in black and white allowed us to have a more…

Bá: Poetic.

Moon: …poetic mix of the images, because they either disappear into black or they can also go and disappear into white. Everything blends a little more and it’s a more abstract version of reality, because you have to make all these visual choices to create a black and white world. It is a poetic approach on how to portray reality, and I think that fits the style of the story better.

Bá: And also, it demands more from the reader. The reader has to make a bigger effort to read a black and white comic, to understand that world, to get those lines and transform them, to translate it in his head.

Moon: Because it’s all so far from this colorful reality.

Bá: So it results in a deeper, more personal, reading experience. And for this type of story we thought it would work better.

You two are twins and you obviously have a much better relationship than the brothers in the story, but was there anything about your experience that you were able to bring to the characters in the book?

Moon: I think the most important thing for us was how we could create and portray the impression that everyone around the twins has of them. Because it doesn’t matter if you’re twins that hate each other or if you’re twins that get along, everybody thinks that twins are the same person.

So if you say something to one, you expect the other to already know. And if one of them feels something, you expect the other to feel the same way and to agree with everything. So right off the bat in the story, Zana is worried that the twins don’t get along, and if they will ever make peace.

That’s how everybody reacts to twins. They want the twins to get along. They can’t understand, they can’t accept the twins are different. And so every character throughout the story is expecting the twins to make peace at some point, and the reader is expecting the twins to make peace at some point. And we could play out these emotions and enhance that aspect of the book because we have so much experience with people thinking we have the same experience about everything.

Do you have the same opinion, Gabriel, or would you like to give a different answer?

Bá: For that question, it is the same thing.

Fabio: We have mostly the same opinions about work. We work very well together because we are on the same page. When it comes to personal life, it gets farther and farther apart. All our problems between one another, they have to do with personal life choices. So I want to leave early, or I want to do something else, or he doesn’t want to come here. It’s something like that. Once we are here and working, everything runs smoothly and we agree on everything.

Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá (W/A, adapted from the novel by Milton Hatoum) • Dark Horse Comics, $24.99